Was the vote on the 2021 American Medal of the Year (AMY) influenced by political correctness? What were the criteria upon which the choice was based? Ursula Kampmann raised these questions in an editorial starting a vivid discussion. Mel Wacks, AMY coordinator, and Philip Atwood, AMY juror, are giving us an insight of how they judge a work of art. This is highly educational for all those who want to learn how to evaluate the artistic value of a medal.

Mel Wacks, Coordinator of the American Medal of the Year Award

I will direct my comments to your editorial, where you asked “What makes an art medal a great art medal?” That is a question that books could be written about. As they say, “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Everyone has a different opinion. Most critics outrightly dismissed Van Gogh’s works as amateur, and some even went as far as to say that is was “strange, intense and feverish.” A review of Tchaikovsky’s 6th symphony was written by W.F. Apthorp from the Boston Evening Transcript on October 31st 1898: “The Pathetique Symphony threads all the foul ditches and sewers of human despair; it is unclean as music well can be.”

I believe that the most important thing in picking the best of anything – from the Academy Awards to the Nobel Peace Prize – is to have the best possible judges. I believe that the jurors who choose the American Medal of the Year are preeminent in the fields of medallic art and numismatics: Philip Attwood, formerly Curator of Medals, Department of Coins and Medals, British Museum and editor of The Medal; Dr. Ellen Feingold, Curator, National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution; Cory Gillilland, Member of the Consultative Committee of Fédération Internationale de la Médaille d’Art and formerly Curator and Deputy Director of the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution; Caleb Noel, editor of The Numismatist; Steve Roach, Editor-at-Large of Coin World, and formerly paintings specialist at Christie’s; Dr. Alan Stahl, Curator of Numismatics, Princeton University, and one of the founders of AMSA; and Dr. Ben Weiss, medal collector and author, member of the board of directors of Medal Collectors of America and its webmaster.

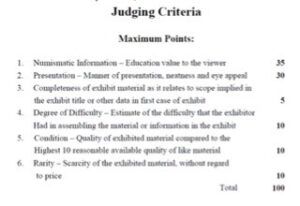

Judges of coin exhibits at U.S. coin shows are usually given precise numeric guidelines, such as these from the Albuquerque Coin Club (left).

Judges of coin exhibits at U.S. coin shows are usually given precise numeric guidelines, such as these from the Albuquerque Coin Club (left).

But I don’t believe that you can judge art with a point system. Art is emotional, an aesthetic experience. And probably no two people experience art in exactly the same way. As Chair of the AMY Jury, I won’t give the judges a point system. I won’t even give them criteria. I will leave it up to each of these distinguished jurors which art medal deserves to be designated the American Medal of the Year by whatever standards they choose. Neither I nor you may necessarily agree with their choice, but ita sit.

Philip Attwood, Award Juror; former Curator of Medals, Department of Coins and Medals, British Museum and editor of The Medal

In recent years competitions and awards have become very much a part of contemporary medallic activity, both nationally and internationally. Examples of the former are the German medal prize, which has been awarded annually since 2006 by the city of Suhl and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medaillenkunst, and the various prizes in the British Art Medal Society’s annual Student Medal Project. One of the premier international prizes is FIDEM’s Grand Prix, awarded at the organisation’s biennial congresses, although there are many others with an international scope. In fact, so many presentations were made at the 2018 Ottawa congress that FIDEM’s executive committee has had to think about how to manage them at future congresses.

Although competitions may in a sense seem antithetical to the spirit of art production (if art has any general overriding function at all, surely it is to bring humanity together rather than set us against each other), I think it’s true to say that they perform a number of useful functions, and this is why they are so popular in many areas of the arts. Through the time that the organisers, jurors et al. give to them, they indicate that there are people who value whatever art form is being judged. The announcement of the winners provides an opportunity for publicity for the art form and the artists, which would not otherwise be forthcoming (and contemporary medals need all the publicity they can get!). They also act as an encouragement for the artists concerned, and particularly of course for the winners. Moreover (and here I speak from personal experience), they make it essential for the jurors to look very intently at a number of medals and to think about them deeply – always a rewarding experience.

The American Medal of the Year, which was recently the subject of an editorial in CoinsWeekly News, is a case in point. I cannot speak for the other jurors but I can try to suggest how I personally approach the role of judging. The first thing to say is that it is never easy. The question I begin by asking myself is how well does each entry make use of the special characteristics of medals. Unfortunately, as no one has yet come up with a totally satisfactory definition of what the contemporary medal is, this is not as helpful as it might at first seem. There are, however, a couple of useful starting points. One is size. In my view medals should sit in the hand. For the American Medal of the Year competition, logistical reasons make it impossible for the jurors to handle the medals. However, the competition organiser Mel Wacks was able to tell us that all the 2021 submissions fitted within this criterion. So far so good.

The next thing I tend to consider as a juror is whether each medal is two-sided or uniface. Ever since the Italian Renaissance, one of the unique characteristics of medals has been the tension they offer between two sets of ideas as expressed by two sides that are intimately related but never seen at the same time; the viewer is compelled to keep turning the medal to unpick its full meaning. This is not to say that I automatically discount one-sided medals. Looking back over time, one can think of many powerful examples. The German medallist Ludwig Gies provides us with many instances: what could be a more eloquent denunciation of war than his Totentanz of 1917? But when it comes to judging a group of medals, for me the single-sided ones have to work quite a lot harder when they’re competing against those that make use of the range of possibilities offered by the two sides.

Having considered these basic points, there are then the all-important questions of how well is the medal executed, what is it trying to say, how well does it articulate its message, how appropriate are the medal’s form and style to the meaning, if there is lettering how is that integrated into the design as a whole, and how does the medal work not only visually but also as a tactile object. With a competition such as the American Medal of the Year, the last of these considerations is particularly problematic, for the jurors are at an unavoidable disadvantage in not being able to handle the medals, having instead to rely on images (but also of course on their long experience of working with medals). The other questions require much thought. The range of issues on which medals can focus is limitless, from subjects of immediate topical interest to matters that are timeless, from declarations of allegiance to a cause to statements of a very personal nature. The ways of making are also wide-ranging, as is the manner in which the message may be conveyed. A degree of opaqueness was regarded as a desirable quality in the Italian Renaissance, the argument being that medals should reveal their secrets only after having been passed around from hand to hand and considered and discussed at length. In our own time contemporary artworks in other media are often nuanced and open to various interpretations. In keeping with this thinking, the two most recent issues of the British Art Medal Society, Weathered the Storm by Matt Evans and The Space In Between by Katrin Hanusch, are examples of subtly allusive medals. Other medals find more forthright ways in which to proclaim their meaning.

The thirty-eight submissions for the 2021 American Medal of the Year award were as diverse as ever. Some celebrated individuals, among them Charles Bukowski, Dara Torres and William Bolcom. Some were political (Donald Trump; Black Live Matter). It was no surprise that several focussed on the Covid pandemic, whilst others took the natural world as their subject or served as commemorations. Some of the designs were extraordinarily complex; others seemingly simple. Portraits, townscapes, surreal visions, fractured vistas, human figures, animal subjects – the variety was immense, and this in itself made the juror’s task more difficult. How to compare chalk with cheese, as the English expression has it.

Various medals particularly drew my eye. The very vivid portrait of Bukowski seemed to capture something of the spirit of the writer, cigarette in hand. A couple of medals of figures wearing masks were poignant evocations of the new world in which we find ourselves. Two medals of German subjects made very effective use of convex and concave forms to produce designs bursting with dynamism. The surfaces of another seemed to be formed almost entirely from the artist’s thumbprints, resulting in representational imagery that worked equally well as an abstract design. Others took the form of assemblages of ironmongery. And then there were the Black Lives Matter medals, one of which stood out from the others. There was no question here of having to tease out the meaning. George Floyd on one side; raised fists on the other. The plaintive ‘I can’t breathe’ as an inscription, contrasted with the angry ‘No justice No peace’. Doubtless it took a good deal of time to make this medal, but to me it looked almost as though it could have been made in minutes, its execution mirroring the urgency of its demands. It seemed actually to shout out loud.

How though to “judge” this medal alongside all the others. I took some time, but what I noticed was that this medal seemed to stay with me. My mind would return to it when I was no longer thinking of the competition. It was this that finally made me give it my vote – a very different sort of medal from those I’ve voted for in the past, but an incredibly powerful one. The thought momentarily crossed my mind as to whether objections might be raised at having a white artist, as I suspected was the case (all submissions are anonymous), taking on (appropriating) a Black subject. But no, the outrage that resulted from the Floyd case was felt by people of all ethnicities around the world and this medal clearly came out of a deeply-felt urge to respond to an horrific injustice. After two rounds of voting, the medal won.

I certainly did not expect the award to be questioned for having been made for the medal’s subject matter rather than its qualities as a medal. Perhaps, with all the accusations of ‘wokeness’ that are flying around at the moment, I should have. This reaction did, however, raise the question in my mind as to whether I would vote for a medal if I disagreed fundamentally with the views it expressed. If it fitted the criteria mentioned above and made its point effectively – more effectively than the other medals in the competition – then yes, I like to think I would. But I could perhaps be more definite if you showed me the medal.

You can find more information on the award at the FIDEM website.

And to learn more about Mel Wacks read his Who’s who article.

Of course you will also find Philip Attwood in our Who’s who lexicon.