New surprising information pertaining to Bank of England polymer notes has surfaced in which their lifespan has been put into question. The Bank of England has reported that nearly 50 million polymer £5 and £10 notes have had to be replaced since they were launched due to wear and tear. New figures offered by the Bank’s own statistics suggest the damaged notes were replaced mainly due to folds, tears, holes and wear on the security foil application. The figures, obtained by the Press Association news agency included information that around 20 million polymer £5 notes and nearly 26 million £10 notes have been replaced because of damage.

The £5 polymer banknote which includes an image of Prime Minister Winston Churchill on the reverse side was launched in 2016 and the £10 denomination which includes a portrait of early 19th century author Jane Austen was released the following year. At the time of their launch, the Bank stated they expected the new notes to last an average of five years in circulation, compared with an average of just 10 months for the £5 denomination and two years for the £10 paper-based series. However, information about the damaged notes reveal the wear and tear was consistent with expectations and the number of plastic notes replaced represents a small percentage of the total number in circulation.

Further information indicated that while the Bank of England expected the polymer notes to have a longer life, they have indicated that it is still too early in the polymer note’s lifecycle to yet understand the rate of replacement of polymer notes. Launching the Bank’s polymer notes was a particular project initiated by Governor Mark Carney who was the previous Governor of the Bank of Canada and presided over their switch to polymer banknotes between 2011 and 2013. Championing the polymer alternative, he stated polymer notes would be cleaner, safer and stronger. Carney, whose term as Governor ends in March 2020 also pointed out that the use of a polymer substrate meant the notes can better withstand being repeatedly folded into wallets or crunched up inside pockets.

There have also been claims by the public that engraved printed elements of the banknotes, including the Queen’s portrait can be rubbed off and that of the foil security application, which on some notes appeared to peel or flake away. Despite the claims, Governor Carney has recently stated the quality and security of banknotes is central to monetary stability. The Bank of England’s position on polymer notes is that they are safer than paper notes and last twice as long. They are also safer for the environment due to their longevity and their recyclability and as such remain supportive of their use.

From the 20th February, the Bank’s third polymer denomination, the £20 note which is part of the “G” series will be released into circulation. The reverse side will feature a portrait of eminent 19th-century painter Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851). For further information about Bank of England banknotes, please visit the banks website.

Polymer Banknotes Introduced During the Governorship of Mark Carney

The subject of a transition from paper-based banknotes to a polymer substrate had been a talking point for some years within the Bank of England and something the British public heard could be a possibility in the future. I had approached the subject during an interview as far back as April 2007 with then-Chief Cashier Andrew Bailey (published in COIN NEWS MAY 2007) The Bank of England had just launched the “F” series £20 banknote featuring 18th century Economist Adam Smith. During this time, Mr. Bailey reiterated: “We don’t have any plans to issue a polymer banknote, we do however look at a whole range of substrates as a potential.”

In November 2011 and on the occasion of the launch of the Bank of England’s £50 banknote in the same series featuring leading 18th century engineers Matthew Bolton and James Watt, I touched upon the subject of polymer notes again. During my interview with Chris Salmon (published in JAN 2012 COIN NEWS) who succeeded Andrew Bailey as Chief Cashier earlier that year, Salmon also commented: “There are no plans to introduce a £5 polymer note, contrary to previous stories in the media. At the same time, it’s not something I would completely rule out forever and it would be wrong to do so.”

It wasn’t until the tenure of Mark Carney who had been Governor of the Bank of Canada previously, that the Bank of England began the process of transitioning the country’s currency notes from paper to polymer. He had overseen Canada’s own transition of adopting an all-polymer “Frontier” note series between 2011 and 2013, becoming the first country in the Americas to do so. Part of the attraction of switching to polymer banknotes was the fact that under ordinary use, they have a greater life-span and in some instances, can last up to four times longer than their paper alternative. During my interview with Andrew Bailey, he had mentioned the fact that many of the letters he received from the public referenced the poor quality of £5 banknotes in circulation. This denomination had been chosen as the first one to print on polymer as the paper versions had an average life-span of around eleven months before needing to be replaced.

With the Bank’s announcement in April 2013 that Winston Churchill would be the new personality to be featured on the reverse side of the new “G” series £5 note, the Bank also confirmed the smallest banknote denomination in circulation would be printed on polymer. The note with its new reverse design and decreased dimensions included state-of-the-art security features only applicable to polymer and was issued in September 2016, becoming the first circulation-type note to be in general use in the United Kingdom. Further versions of the new polymer note were also launched in due course in Scotland and Northern Ireland through the six commercial banknote-issuing entities.

One of the immediate controversies to become a point of contention was when the Bank of England confirmed reports that the new polymer £5 note contained traces of tallow in the substrate, a rendered animal fat derived from suet and which was a concern for vegans and religious groups. The Bank addressed their concerns but reiterated they would continue to produce banknotes printed on the same polymer substrate and were committed long-term to the programme.

Following on the issue of the £5 note, it was announced by Mervyn King – one of the last tasks he undertook as Governor that early 19th century novelist Jane Austen would grace the reverse side of the new £10 banknote. This denomination was issued in September 2017 and by this time the British public had become accustomed to the new plastic notes. On the 20th February, the country’s newest polymer banknote, that of the £20 denomination will also be issued featuring eminent 19th century artist JMW Turner (1775 – 1851) which was unveiled in October 2019 at the Art Centre in Margate bearing the artist’s name.

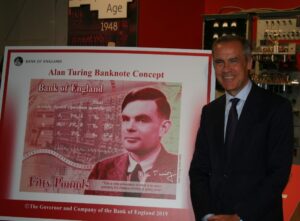

Completing the new “G series” family of banknotes will be the £50 denomination featuring an image of Scientist and computer genius Alan Turing (1912 – 1954) which is expected to be released in 2021.

The author, Michael Alexander, is president of the London Banknote and Monetary Research Centre.

Recently, he wrote about the curious case of the elusive 50 Pence Brexit Coin.

Michael also reported on the announcement that Turing would feature the new £50 banknote.

You can learn more about Great Britain’s banknotes on the Bank of England website.