In the mid-1750s, a young enslaved albino woman, named Amelia, journeyed from Jamaica to London, where she not only attracted the attention of a curious British public, but also of the most renowned naturalist of her time: Carl Linnaeus.

Like the Bank of England, the Linnean Society of London, a natural history learned society, has been working to uncover its “hidden histories”. These include the stories of black and indigenous artists, collectors, and others who have contributed to knowledge of the natural world. Sadly, in many cases they have never been recognised and their stories have been forgotten.

The Bank’s exhibition on Slavery & the Bank features a coin of Amelia Newsham, an albino enslaved young woman, who was the object of scientific curiosity in 1758. Letters kept at the Linnean Society shed more light on the difficult and devastating transatlantic story of Amelia.

You may be wondering why this albino woman seemed so fascinating. In the 1700s, scholars were dedicated to studying, sorting and naming the natural world – particularly the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). Linnaeus sorted, or classified, the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms in his famous book, Systema naturae (“Systems of Nature”), and was one of the first to include humans in the kingdom of animals. He named our species Homo sapiens (“wise man”) and divided it into four varieties based on geographical origin and skin color. Linnaeus constantly updated his books with new information, and in the 10th edition of Systema naturae in 1758, he split the group Homo into two species: one being Homo sapiens (a “diurnal” species, or active in the day) and the other Homo troglodytes (a “nocturnal” species, or active at night). Homo troglodytes was a species based on ancient literature, similar to a cave dweller, which Linnaeus was keen to investigate.

On Display in London

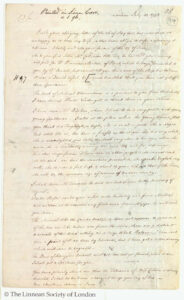

In February 1758, when Linnaeus heard that “A troglodyte can be seen in London”, he wrote to his London contacts, the linen merchant and naturalist John Ellis (1710–1776), and a young Swedish physician and former student of Linnaeus, Pehr af Bjerkén (1731–1774), saying:”I learn by letters from London, that a Troglodyte, or Homo nocturnus, (…) is arrived in your capital. (…), I therefore most respectfully beg of you to examine this animal with attention.”

Linnaeus then listed a few questions to guide them when putting together their observations.

So, during the spring and summer of 1758, the ‘animal’ visited by Ellis and af Bjerkén, examined by gentlemen of the Royal Society, and gawped at by Londoners for the price of 1 shilling was, in fact, the young enslaved albino girl, Amelia. Born in Jamaica around 1748 from black enslaved parents, she was sent to England in 1753. She was sold to John Burnett, who kept a bird and beast shop off St Martin’s Lane in London – as shocking as it is to us now, in the eighteenth century it was common for men and women with unusual physical attributes to be paraded with other animal curiosities. Amelia’s albinism had made Linnaeus think that she was nocturnal, and a possible Homo troglodytes.

Manuscripts and letters found in the Linnean Society reveal how the visits went, and provide a detailed description of Amelia by both men. Though af Bjerkén’s letters make for uncomfortable reading, John Ellis’s letter is rather more humane, depicting Amelia as a “young woman” who speaks English well, and who can read. Both concluded that the girl was not a Homo troglodytes, but a ‘strange’ specimen of Homo sapiens.

Amelia’s Later Life

Amelia toured the country as a curiosity for most of her life, and was baptized in Exeter, in Devon, as Amelia Harlequin. Believing her baptism made her free, she left John Burnett, exhibiting herself by her own rules. Souvenir coins were made with the likeness of the “White Negress” and sold at fairs like Bartholomew fair, in Smithfield, London, where she exhibited herself. She married an Englishman, Mr Newsham, and had at least six children.

The letters kept at the Linnean Society shed light on how, as an albino, she puzzled 18th century scientists all across Europe. From other sources, we know that Amelia Newsham eventually took her destiny into her own hands, turned the European curiosity for the unusual and exotic to her advantage, and became a shrewd businesswoman, a wife and a mother.

This article, written by Dr Isabelle Charmantier, Head of Collections, The Linnean Society of London, was first published on 26th August 2022 on website of the Bank of England Museum.

This article is an adaption of a blog originally published by the Linnean Society of London. If you would like to learn more about Amelia Newsham’s story, including reading more archival excerpts, read Black Lives in the Linnean Society Collections: Amelia Newsham.

Learn more about the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Here you can read how the Bank of England was involved in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Do you know about Humphry Morice? A slave trader, embezzler of the Bank – and also its Governor, making a reckoning with his legacy a massively important undertaking.