Humphry Morice was a slave trader, embezzler of the Bank – and also its Governor, making a reckoning with his legacy a massively important undertaking. As Curator Jennifer Adam noted in her blog post Beginning the Exhibition on the opening of the Museum’s current exhibition “Slavery & the Bank”, “the Bank of England was founded and came to prominence at a time when… Britain was at the forefront of the transatlantic slave trade.” Its offices of Director and Governor “were held by wealthy and successful businessmen, many with commercial interests in slavery.” Of all the men with connections to both the Bank and the trade in enslaved Africans, none was connected more intimately to both than Humphry Morice. A longtime Director of the Bank, Humphry Morice became Deputy Governor in 1725 and then Governor in 1727, serving in that role until 1729 before returning to the ranks of the Directors. All the while he also served as a Member of the House of Commons.

Humphry Morice was also the biggest London-based trafficker of enslaved human beings from Africa to the British colonies in America – the “prince of London slave merchants,” as Hugh Thomas dubbed him in his book The Slave Trade, a phrase I borrowed for the title of my own book on Morice. Between 1704 and 1732, Morice was responsible for outfitting something like 110 voyages to Africa, transporting over 30,000 individuals to Jamaica, Barbados, Virginia, and elsewhere in America. This was his principal commercial activity, and it is for this that he must chiefly be remembered.

And yet, though for us Morice’s slave-trading represents his most evil legacy by far, to his contemporaries the worse crime was the fraud he perpetrated against the Bank at the end of his life. Morice had always prided himself on having the most innovative and effective strategies for trading with Africa. By the late 1720s, however, merchants from Bristol had begun to improve upon his methods while also taking advantage of their easier access to Atlantic trading lanes. As his ship captains found it increasingly difficult to exchange European and Asian goods in African ports for enslaved persons to bring to America, Morice found it increasingly difficult to fund his vast transatlantic operations. So, between May and November 1731, Morice forged thirteen separate bills of exchange – payment instruments not unlike modern cheques – and cashed them at the Bank, receiving £27,700 in total (roughly £3.26 million in today’s currency).

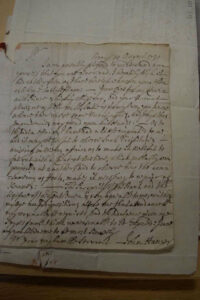

This letter to Morice of 19 August 1731 from John Hanger, himself a Bank Director and former Governor, cautions him not to ‘fall out with a Cheat at One time, which probably was projected at another’ – possibly a veiled warning that Hanger had detected Morice’s fraud.

Humphry Morice died on 16 November 1731 under mysterious circumstances. London newspapers gave “the Gout in his Stomach” as his cause of death, but according to rumor, “Tis supposed he took poyson.” His widow Katherine Morice briefly took over his slave-trafficking operation and served as executor of his bankrupt estate. In this role she attempted to salvage some portion of the family’s wealth against the claims of Humphry’s many creditors, including the Bank, which unsuccessfully sued the estate in the Court of King’s Bench for restitution of £28,993 8s 1d. This litigation is documented mostly in the National Archives, but the bulk of Humphry Morice’s papers – business and personal letters, marine insurance accounts, orders to his slave ship captains, and others that provide an astonishingly clear view of his way of doing business – are held by the Bank’s own Archives.

If you would like to learn more about Humphry Morice’s life and legacy, visit the exhibition Slavery & the Bank.

The article was written by Matthew David Mitchell, Associate Professor at the Department of History, Sewanee, University of the South (USA). It was first published on the blog of the Bank of England Museum.

In a temporary exhibition the Bank of England investigated their involvement in the Transatlantic Slavery.

To learn more on the subject, don’t miss our article “A Lesson in Economic History: The Transatlantic Slave Trade”.