With the exhibition „New Images in the Age of Augustus: Power and Media in Ancient Rome“, the Bucerius Kunst Forum is spotlighting a central chapter in the visual culture of antiquity: the veritable boom in imagery under Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. Curated by Prof. Dr. Annette Haug and Prof. Dr. Andreas Hoffmann, the show reveals the new understanding of pictorial language and strategies that took hold during this period as well as innovative uses of media and materials. This sea change is illustrated based on slightly more than 200 objects, including statues, portrait busts, reliefs, wall paintings, coins and ceramics, lent by the Louvre in Paris, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Capitoline and Vatican Museums in Rome, the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, and other major European museums and collections. This is the first Augustus exhibition in Germany in 34 years.

The reign of Augustus marked a turning point in Roman history. Applying radical methods, Augustus was able to prevail over his opponents to become absolute ruler in Rome. As Rome’s first emperor (27 BCE to AD 14), he not only possessed immense power but also implemented novel communication strategies. Images would play an unprecedented role during the Augustan Age. Visual cues were omnipresent as never before, in particular portraits of the Emperor, and a great interest on the part of the general public in figural representation ensured its proliferation everywhere. New clients were part of this upsurge, because for the first time not only elites but society at large could participate in both commissioning and appreciating works of art. The economic circumstances of the time favoured this flowering of the arts: successful wars brought greater prosperity, the discovery of quarries in Luni ensured wide availability of marble, and skilled copyists now made it possible to serially reproduce artworks. Augustus made strategic use of a variety of media for visual communication: portrait statues, busts, reliefs, images and inscriptions on architecture as well as the construction of new public buildings. Coins and jewellery likewise spread his intended messages in all walks of life and throughout the empire. During his reign, Augustus periodically changed the way he staged his likeness to suit the respective political and social situation, thereby shoring up his power base.

Tastes underwent some changes in the private realm as well. Interiors were adorned with a profusion of panel paintings on the walls and figural motifs on ceramics and furniture, while private courtyards and gardens featured statuettes as well as richly decorated water basins and fountains. Rather than being politically inspired, the themes here revolved mainly around the gods Bacchus and Venus.

The way in which Augustus made targeted use of persuasive imagery to achieve his political ends seems quite relevant to our world today. Staged images still play a significant role in the political arena, especially in dictatorships and controlled democracies as well as during wars, which are increasingly also media wars. Parallels can be found between the transition from the late Roman Republic to the Principate, Augustus’s autocracy, and contemporary regimes that lend Augustan imagery a fascinating topicality.

The exhibition illustrates the new approach to imagery during the Augustan Age in five chapters:

- Portraits of the Emperor and Empress;

- New narratives and memorable images;

- The new cityscape;

- New and old cult representations;

- Domestic imagery between tradition and innovation.

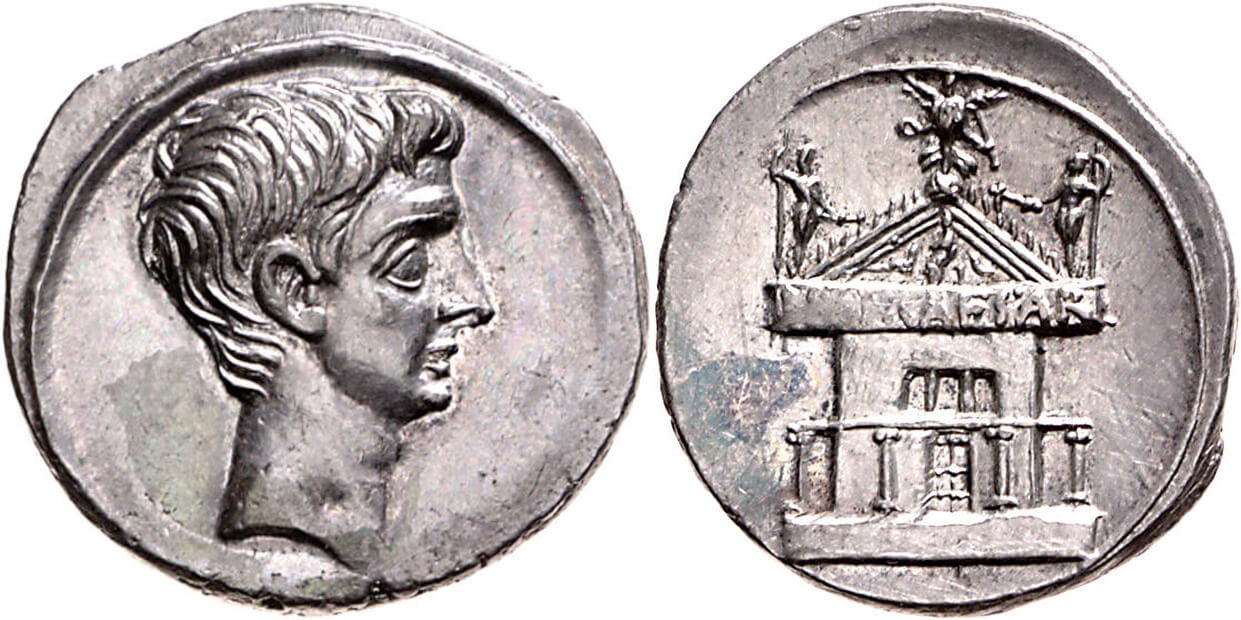

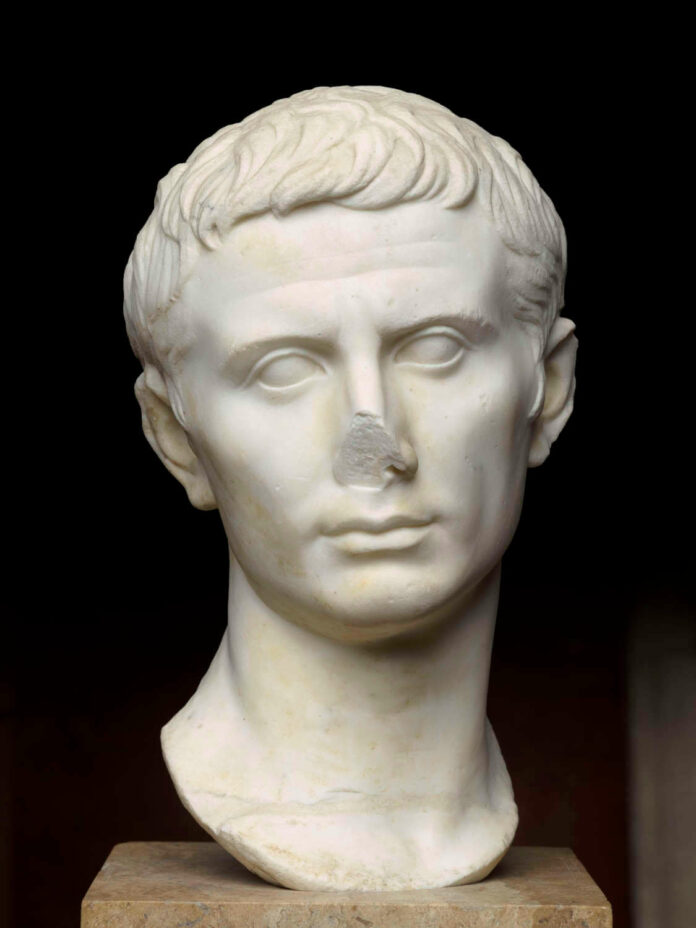

In the first section of the show, pictorial innovations are demonstrated by the way in which the Emperor chose to portray his own likeness. Various portrait types trace the development from the image of youthful saviour of the state to that of military commander and emperor and onward to the revolutionary invention of the imperial portrait. For the first time, a prominent woman also took pride of place in the public eye with Augustus’s wife Livia, whose image was no less carefully curated. Through likenesses in the form of portrait heads, busts, statues and coins, which circulated as never before throughout Rome and the provinces, the imperial house was able to communicate with the people via a variety of media.

Augustus couched his self-portrayals in new narratives and memorable images representing the history of the city of Rome, the divine origins of his own family, his various successes and the generally triumphant tenor of his reign. These pictorial motifs were displayed on prominent new buildings, for example, and attracted attention throughout the empire. Examples on view in the exhibition include wall frescoes, architectural fragments, works in terracotta, statues and statuettes, and reliefs and inscriptions.

Rome’s cityscape was transformed during the Age of Augustus into a major construction site as prestigious new buildings went up everywhere. While sacred sites had previously been the main locus for imagery, now secular buildings as well were embellished with pictorial programmes. The exhibition examines selected examples, such as the Forum of Augustus. Augustus publicised important buildings and construction projects across the empire by reproducing them on coins.

Among the most prominent building complexes of Augustan Rome was the Temple of Apollo, patron god of Augustus, on the Palatine Hill, where the Emperor lived. During Augustus’s lifetime the cult of the Emperor was already integrated into the sites where the common people worshipped. At crossroads in the city districts, citizens worshipped their personal guardian deities, the Lares. The rites at the Lares shrines were now reorganised to link them to the person of the Princeps. Shortly after Augustus’s death, sanctuaries dedicated to the Emperor’s cult were already being built in many cities. Based on statues, precious herms, busts, altars, frieze fragments and images on terracotta slabs from Rome, Herculaneum and Cuma, the exhibition conveys the figural motifs that could be found in places of worship.

The new devotion to imagery in the early imperial period was particularly evident in the private sphere. Homes were adorned inside with murals and picture galleries in the third, or ornate, style, while affluent citizens decorated their gardens with sculptures as well as marble and bronze tripods and candelabras. Tableware was now also discovered as a new pictorial medium. The motifs revolved around tales of Bacchus and Venus and were thus far removed from public political imagery.

The exhibition attempts to render building complexes such as those making up the Forum of Augustus, the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill, the Temple of Apollo in Pompeii and the Augusteum of Herculaneum as well as Pompeiian residences including the Augustan Casa di Cecilio Giocondo and the Casa della Fortuna spatially tangible at least in part in the exhibition so that visitors can imagine what they must have been like for those living in the Augustan period.

A catalogue will be published by Hirmer Verlag to accompany the exhibition, featuring essays by international professors of classical archaeology, museum directors and curators.

The exhibition is to a great extent a German-Italian project. An international honorary committee including the Director General of Italian Museums, Massimo Osanna, brought together some of the most important museum directors in Italy. They have all devoted themselves to working closely with the Bucerius Kunst Forum and arranging loans. A large number of Italian museums are participating as lenders, including the Vatican and Capitoline Museums, the Colosseum Archaeological Park, the Palatine Museum, the Uffizi Gallery, and the National Archaeological Museums of Florence, Naples, Spoleto and Venice. The Italian Ministry of Culture played a central role in making the exhibition possible by approving works on loan. The exhibition is taking place under the auspices of the Embassy of the Republic of Italy.

For more information about the exhibition and how to visit, please visit the Bucerius Kunst Forum website.

Read more about Augustus and the beginning of a new era.

Honestly, what do you think: was Augustus a peacemaking emperor or a mass murderer?

His coinage clearly illustrates how Augustus saw the world or rather wished it to be seen.