How can you secure the loyalty of mercenary troops in times of turmoil and continuous wars? 2500 years ago as today the secret is money. Precious metal in those days, minted silver and gold. And to make sure the soldiers knew where their pay came from, the Diadochs, Generals, of the Godlike Alexander the Great, first added their names and new royal titles, and then their individual faces to the coins they paid out in abundance.

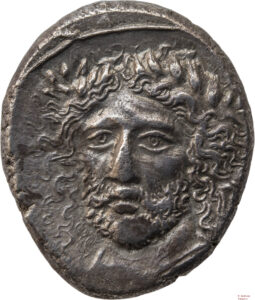

Still today these coins are our major source of knowledge of these Royal individuals. At that time showing individual portraits was a relatively new invention. Some two centuries earlier Greek celators employed by Persian Satraps, governors for the Achaemenid kings, and local kings in Asia minor (Lydia, Lykia, Cilicia), began giving images of bearded men on coins more and more individuality, now commonly accepted to be individual portraits.

Expressing human individuality was however still not wanted in the Greek motherland, not acceptable in these mainly city based democratic societies. Even Alexander the Great kept avoiding portrait individuality on his coins, even though his appearance was likely projected into the head of the beardless Heracles with the lion-skin on his ubiquitous silver coins.

In the early years after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, this barrier fell. Some of the following coin portraits are amongst the best ever made. We can identify and differentiate many hellenistic rulers just by looking “in their face” on coins.

Some Royal portrait types document closely natural changes of the king’s appearance, like the progressive growth of a beard. Later Hellenistic rulers who – as Alexander the Great – wished to be associated with Gods tended also to be shown with more idealized portrait types, combined with godly attributes.

Roman generals inherited the tradition of Royal portraits when they destroyed the hellenistic world (and subsequently undermined the democratic principles of their Roman republic). They brought the concept of a ruler’s portrait to Rome, where it continued in Roman republican and later imperial portraits. Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the Roman general who defeated Philip V of Macedonia, had himself portrayed on Greek gold coins echoing the portrait style of Philip V.

When Julius Caesar placed his portrait 44 BC on Roman coins it created still an uproar in Rome. Since Marcus Antonius and Octavian it had already become common practice.

The following Roman emperors continued this hellenistic tradition and very successfully “coined” their portraits. So successfully was their portrait branding, that many of us still today recognize an Augustus, a Nero, a Hadrian. One can assume that there must have been at least a certain level of Royal portrait type control already in the Hellenistic kingdoms.

While only very limited numbers of Greek Royal portrait sculpture survive to our time, the massive numbers of surviving coins, named and often dated, are our major source of what we know of those kings. Some kings are actually completely absent from literature, we know of them from only their coins. Most of the Bactrian kings fall into that category.

The traditionally close collaboration between numismatic and archaeological scholars, coin collectors and trade plays a key role to advance our knowledge of this important and exciting period. For example a previously completely unknown Greek king was recently discovered in a private collection: Hippokrates Autokrator Nikephoros.And more mysteries remain to be solved, like another coin of a private collection with the name Erotos, who is so far not attributable. If you find a way forward to attribute this one, please contact the author…

Literature:

- Fittschen 1988: Klaus Fittschen, Griechische Porträts, (Darmstadt 1988).

- Fleischer 1991: Robert Fleischer, Studien zur Seleukidischen Kunst, Band 1, Herrscherbildnisse, DAI (Mainz 1991).

- Pangerl 2017: Andreas Pangerl (ed), Portraits, 500 Years of Roman Coin Portraits, Staatliche Münzsammlung, (Munich 2017)

- Pangerl 2020: Andreas Pangerl (ed), Portraits, 400 Years of Hellenistic Portraits, Staatliche Münzsammlung, (Munich 2020)

- Richter 1965: GMA Richter, The Portrait of the Greeks, (London 1965)

- Smith 1988: RRR Smith, Hellenistic Royal Portraits, (Oxford 1988).

With the publisher Staatliche Münzsammlung München Andreas Pangerl published two books on the subject, 500 Years Roman Coin Portraits, and 400 Years Hellenistic portraits.

Find out more on the website of the Munich State Coin Collection. Alternatively, you can also contact the editor.

In her book “MenschenGesichter” (Human faces), Ursula Kampmann tries to answer the question of why human portraits were the typical motifs on coins for millennia. Here you can read all parts of the series.