Athens takes pride in its Numismatic Museum, and they are right to do so. Even in our hotel the Museum’s address and opening hours had been put up for everyone to see, alongside those of the National Museum and the Acropolis Museum. Of course, we were looking forward to our visit. It was meant to be a highlight of our journey. After all, it is one of the most important numismatic collections of the world and, what’s even more, it is located in the mansion of the famous amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann! No coin enthusiast would be able to resist this combination.

Founding a Museum as an Act of Nationalism

Let us first take a look at the history of the Athens Numismatic Museum, as it has had a lasting impact on its collection. A national coin collection for Greece was founded as early as on 21 October 1829, by Ioannis Kapodistrias. If you collect euro coins or at least take a look at them every now and then, you probably know that this man is featured on Greek 20 cent pieces.

And there is a reason for it: unlike King Otto or George I, Ioannis Kapodistrias is considered the founding father of autonomous Greece. He created the basis for institutions that strengthened Greek nationalism. These include, for example, the Archaeological National Museum and, of course, a numismatic collection. Back then, both were located at the seat of the government in Aegina and were rather small. The coin collection comprised exactly 359 pieces. Today it has 600,000 items.

The collection owes this enormous growth not only to excavation finds but above all to gifts from abroad: many wealthy Greeks living in exile donated or bequeathed their coin collections to the Greek nation. Let us mention some names like the Zosimas brothers (18,000 coins and medals), Pavlos Lambros (the acquisition of his unique collection of coins of the Ionian Islands was financed with 25,000 drachmas provided by Alexandros Mourouzis, who lived in Saint Petersburg) and Ioannis Dimitriou, who entrusted the museum his collection of about 10,000 coins of the Ptolemies and Alexandrian tetradrachms that he had gathered in Egypt. These are just the most important of the many collectors whose collections are responsible for the fact that today’s exhibits are of outstanding quality, and do not only stem from hoard finds and excavations but from the most famous coin dealers of their era.

The numismatic collection soon grew so much that a separate place was needed to store it. Since 1867 it had been kept in an annex of the National Library of Greece – conditions that are not ideal in terms of security. It was a tragedy that, even though moving it had been planned since 1887, the collection was still there when a group of thieves broke in. A large part of the irreplaceable collection probably ended up in a melting pot at that time.

The Era of Svoronos

In 1890, Ioannis Svoronos was hired as a numismatist at the coin collection of Athens. The scholar, who had trained in Berlin, London and Paris, became the director of the institution in 1899 and served in this capacity until 1922. Under his lead, the numismatic collection gained international reputation. His works on ancient Crete and Ptolemaic coinage – which are based on the donations of Ioannis Dimitrious – are still standard references today, as are several articles of the Journal Intérnational d’Archéologie Numismatique, which was founded by him.

His attitude towards the coin trade – and the fact that both trading coins and exporting ancient objects was considered perfectly legal in 1922 in Greece – is evidenced by a small remark in one of his works, a publication of the counterfeits of Constantin Christodoulos (translated from French): “The most frequent victims of the counterfeiters are the caravans of thousands of tourists, who want to take at least one ancient coin as a souvenir of their trip to Greece. They depart feeling satisfied with their beautiful acquisitions; but once they discover that they have been robbed [as they were sold counterfeits], they declare in their homelands that modern Greece still houses skilled robbers in its glorious capital – even though the legendary kings of the mountains no longer exist. To react to the shame of seeing my country being discredited, I started to make the masterpieces of Athenian counterfeiters public once I was appointed director of the Numismatic Museum. As it was the only measure to eradicate counterfeiters and all powerful clandestine antiquities dealers, I suggested to the government of my country at the same time to take trade into their own hands, just like the museums of Egypt, Berlin, London etc. did: auctions could be held to exchange duplicates and all the coins and other ancient objects, which equal millions and lie dormant in our museums. By selling them, our museum could acquire large financial means. This would allow us to acquire all the hoards that peasants and other people happen to find – just like our Archaiokapeloi regularly does it, at a good price and without being fooled.” (J. N. Svoronos, Synopsis de mille coins faux du faussaire C. Christodoulos. Athens 1922. Reprint Basel – Amsterdam 1963, p. 3.)

Moving to Schliemann’s Mansion

Since Svoronos, many directors of the Numismatic Museum have worked at an international level. Mando Oekonomides, who was director from 1964 to 1994, succeeded in getting the political agreement to move the numismatic collection to the Schliemann mansion. Her successor Ioannis Touratsoglou, director from 1994 to 2002, realized the relocation. It is not clear who runs the museum today. According to the in-house website, Georgios Kakavas is head of the museum while Evangelia Apostolou is responsible for the numismatic department. According to the German Wikipedia, Despina Evgenidou is the museum’s director. Thanks to CoinsWeekly, you can find the answer to this riddle: the Numismatic Museum does not only have a Director but also a Honorary Director.

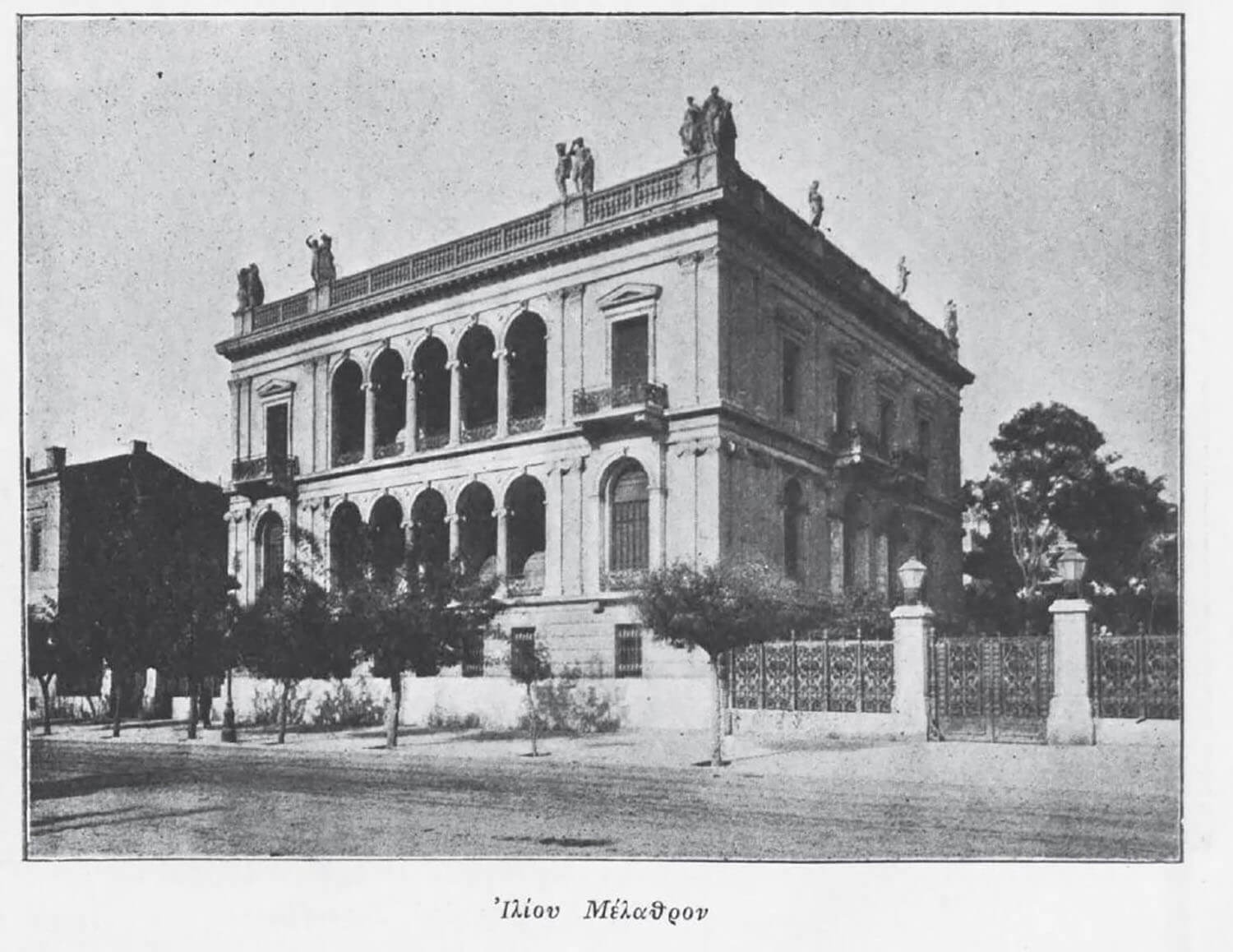

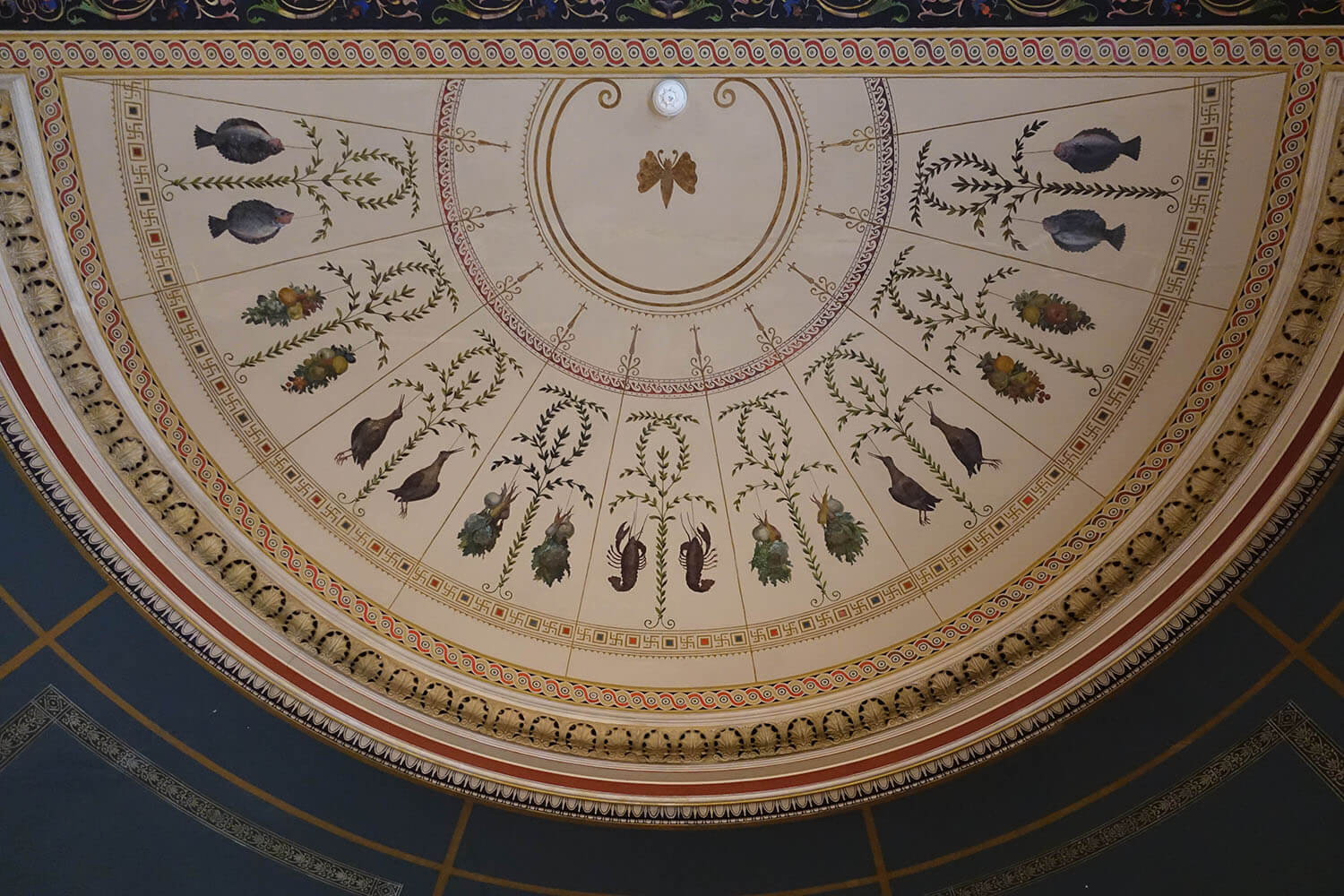

In high spirits, we headed to what was supposed to be the highlight of our stay in Athens. We were immediately captivated by the Schliemann mansion. It is the childhood dream come true of an antiquities fetishist who made a lot of money. Schliemann said about himself that he hated the narrow rooms of the poor dwellings of his childhood. That is why he used his money to build a house where air and light were omnipresent. Therefore, the Schliemann mansion is the perfect location of a museum: today’s tenants can only dream of rooms of such size and height.

Schliemann’s Dream of a Mycenaean Palace

On 30 January 1881, proud Heinrich Schliemann and his Greek wife Sophia inaugurated the magnificent house. Ernst Ziller, the then most popular artist of Athens, was the architect. Building it cost 439,650 drachmas. It was designed in the Neo-Renaissance style. This was quite programmatic. At that time, the style of a building was chosen according to its purpose, and the Neo-Renaissance was associated with education and the bourgeoisie.

Heinrich Schliemann’s Coin Collection

Heinrich Schliemann was not only a renowned hobby archaeologist, he was also a coin collector. We know this because the numismatist Achilleas Postolakas, who was born in Vienna and trained there, was appointed to the numismatic collection of Athens in 1856 and catalogued Schliemann’s collection. The original manuscript has survived. Schliemann collected Greek, Roman and late Roman coins, which were sold by his widow to the Numismatic Museum of Athens in 1928.

The coins were kept in the study. On the first floor there was kind of a private museum with objects from his excavations, which he was happy to show personally to curious visitors. We, too, admired the magnificent first floor. And, of course, we were thrilled by the quality of the coins that are exhibited there today.

The wealth of coins of the city of Athens is particularly impressive. It contains rarities that can rarely be spotted in high-class auction sales: from early heraldic coins of Athens that were minted before Athena conquered the obverse to a specimen of the famous decadrachm series to a 295 gold stater minted from the temple treasure that was kept on the Acropolis during the siege by Demetrius Poliorcetes and a reverse die for tetradrachms, not to mention a state emergency issue of the kind that Aristophanes made fun of in his comedy “The Frogs” 725-276: „Just like we treat old and trusted coins along with the new gold. Both are pure metal and used all over Greece and by the rest of the word, but we don’t use them at all and, instead, we work with these useless copper coins, which we’ve only just minted a day or two ago with the worst possible stamp!“

Hoard Finds in the Numismatic Museum

Of course, the collection of the Numismatic Museum also comprises hoard finds that were brought there from all over Greece: The hoard of Karditsa was discovered in 1970 and buried around 440 BC. It contains an interesting assemblage of Aeginetic staters. Experts will be thrilled by the find of Olynthus, which was buried in 348 BC and unearthed in 1931. We know exactly when it was hidden because the hoard is associated with the conquest of Olynthus by Philip II. The specimens of the Corinth coin hoard are magnificent too. They were buried after 330 BC and discovered in 1930. The gold staters of Philip II and Alexander III were hidden in the temple of Apollo along with a gold necklace.

Expulsion from Paradise

As we were standing there, thinking that we arrived in numismatic paradise, the archangel came with his flaming sword, i.e. a museum guard who kindly informed us that our 15 minutes were up. 15 minutes? Confused, we looked at each other. Yes, the guard told us, each visitor of the numismatic museum was only allowed to spend 15 minutes on each floor. Due to Covid. That’s a new rule.

We were speechless. The Numismatic Museum was not the first museum we visited in Athens. It was, to be precise, the sixth. In each of the five previous museums visitors had to wear masks and only a certain amount of people was permitted per room – by the way, all the Greek museums we visited later adhered to these two rules too. A maximum number of visitors? That’s okay for me. It is understandable and reasonable. But it is still beyond my comprehension why the numismatic collection, of all places, adopted a 15 minute rule. It is a museum with a wealth of items – I believe there are more than 1,000 pieces on the first floor – and very few visitors – during our entire visit we only encountered one other collector, who was also sent away, and a family with two children hurrying through the halls.

I appealed to reason – after all, there was just one other person on the floor and nobody was waiting outside. I appealed to the heart – I told them that we were coin enthusiasts, come from Germany and will not have the chance to see the treasures of their collection anytime soon. Yes, I even had them take me to the numismatist in the basement and asked to be granted a little more time given that I was a colleague. But both of them, the guard and the numismatist, rejected my request without turning a hair. I should have sent an email to the director before coming there, was the unhelpful tip of the colleague. The director could have permitted me to stay longer. She was sorry, she said, but that’s the way it was: 15 minutes per floor, period.

We were annoyed. We hurried through the rest of the museum – Byzantine coins and seals and Middle Ages on the first floor, modern coins and medals on the second. That’s why I cannot show you any pictures of the exhibition.

When we left the Numismatic Museum, still snorting with rage, a friendly guard, who had noticed how incredibly disappointed we were, rushed over to us. She told us about a trick: leave the museum, have a coffee in the café next door, buy another ticket and spend another 15 minutes on every floor.

Great idea: that’s one way to make your visitor numbers go up.

Here you can find the Greek website of the museum. Thanks to Google Translate you will surely understand most of it. By the way, I only found the website thanks to Wikipedia.

If you want to travel to Athens in times of Covid and be granted the permission to stay longer than 15 minutes on every floor, send an email to the director of the museum.

The last time we were in Greece was exactly ten years ago. If you want to travel with us through the north of the country, read the numismatic diary.