The British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) announced the discovery of the largest hoard from the immediate post-Conquest period ever unearthed.

The hoard, which primarily includes coins depicting Harold II (1066), the last crowned Anglo-Saxon king of England and his successor, William the Conqueror (1066-87), first Norman King of England, is also the largest Norman hoard found since 1833, and the largest ever found from the immediate aftermath of the Norman Conquest.

How the treasure was discovered

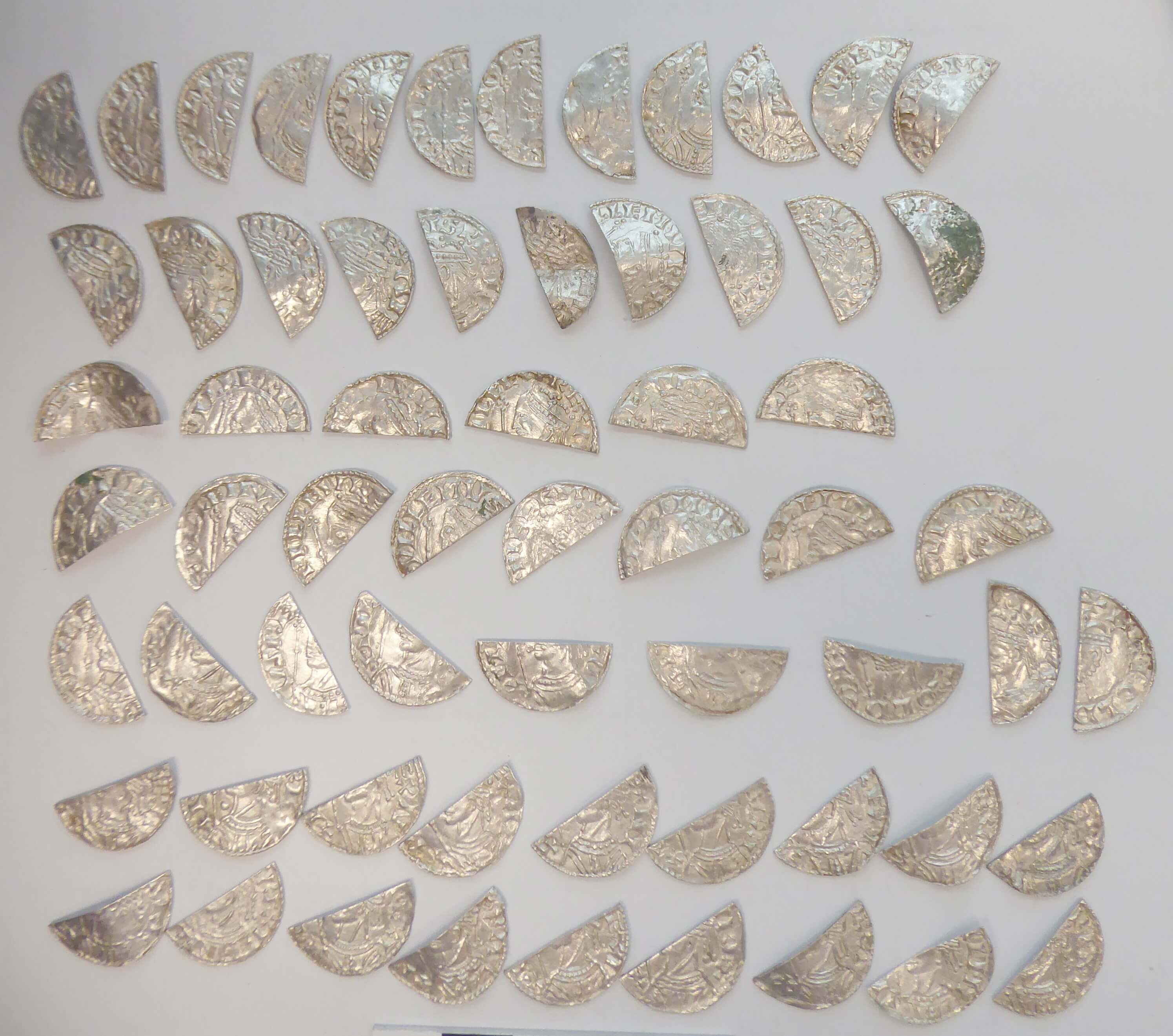

In January 2019 a group of metal-detectorists including Lisa Grace and Adam Staples were searching on land near the Chew Valley, Somerset when they discovered an initial group of coins. Along with five other colleagues they found a total of 2,528 coins dispersed in the ploughsoil over a small area. The find was reported to the local Coroner, as required under the Treasure Act 1996. The coins were brought to the British Museum the day after being discovered, where they have been cleaned for identification purposes and catalogued in a report for the Coroner. The hoard is in good condition and is made up of 1,236 coins of Harold II and 1,310 coins of the first type of William I, as well as a number of fragments.

Treasure or not treasure?

It will now be examined by the local Coroner to confirm if it is Treasure. Under the Treasure Act, which in England is administered by the British Museum, museums are given the opportunity to acquire finds of Treasure. If the finder(s) and owner of land where Treasure is found wish to claim a reward, the find is then valued by the independent Treasure Valuation Committee and museums have to raise funds to acquire it. If this find is declared Treasure by the coroner, the Roman Baths & Pump Room in Bath have expressed interest in acquiring the hoard for their collection.

The hoard testifies of the fight against the Normans

The discovery is hugely significant, not least because it contains almost double the amount of Harold II coins compared with all of the previous known examples combined. Most of these Harold coins were produced in Sussex and the South East, which indicates financial preparation in the area to resist the Norman invasion. In addition, the hoard makes up five times more examples of the first coin type issued by William I, following his coronation on Christmas Day, 1066.The hoard thus provides an unprecedented opportunity to examine changes in the coinage in the immediate aftermath of the Norman Conquest. Preliminary analysis indicates the presence of mints previous unrecorded for Harold and William respectively, including coins of Harold from the local mint of Bath. There are also suggestions that the Norman die cutters producing these coins struggled to understand Old English based on the quality of spelling on the coin.

The Chew Valley hoard also contains the first known examples of a ‘mule’ between Harold and William. Mules are coins with a design from different coin types on each side of the coin, indicating that the moneyer for the coin re-used a die to create one side. An early form of tax evasion, this avoided the moneyer paying a fee each time new dies were acquired – re-using an old die one illicitly avoided the fee. In this case, the mule demonstrates that coins were produced with Harold II’s name on after William I had taken control of the country following the Norman Conquest and established coinage of his own. The hoard also includes a rare example of a mule of Harold’s predecessor Edward the Confessor (1042-66) and William I.

The historical relevance

The exact circumstances in which the hoard was buried are uncertain. It was buried in the period c.1067-8, but in 1067 the Welsh attacked Herefordshire, in 1068 William himself besieged Exeter, and later the same year the sons of Harold returned from Ireland, raiding around the mouth of the Avon, Bristol and down into Somerset. The last of these is the most likely to be directly associated with the hoard, but all three indicate a period of unrest in the south-west which might lead to wealth being buried for safety.

Gareth Williams, Curator of Early Medieval Coinage, said: “This is an extremely significant find for our understanding of the impact of the Norman Conquest of 1066. One of the big debates amongst historians is the extent to which there was continuity or change, both in the years immediately after the Conquest and across a longer period. Surviving historical sources tend to focus on the top level of society, and the coins are also symbols of authority and power. At the same time, they were used on a regular basis by both rich and poor, so the coins help us understand how changes under Norman rule impacted on society as a whole.”

Councillor Paul Crossley, cabinet member for Community Services at Bath & North East Somerset Council, said: “We are very excited about the discovery of this important hoard in North East Somerset with such strong connections to our area. If we are able to acquire the coins, we will work to display them locally, as well as partnering with the British Museum to make them available for loan to other exhibitions so that they can be seen by a wider audience.”

Lisa Grace and Adam Staples, finders of the hoard, said: “It’s an amazing feeling to have unearthed this spectacular hoard. We’ve been dreaming of this for 15 years but it’s finally come true.”

Rebecca Pow, Minister for Arts, Heritage and Tourism said: “This is a very exciting discovery and important finds like this shed new light on the remarkable and fascinating history of our country. If the Coroner rules that the Chew Valley Hoard is Treasure, then I hope it might find a new home in one of the UK’s museums, where it can be seen, studied and enjoyed by all.”

For more information on the Portable Antiquities Scheme go to the PAS website or read our article on 20 years of PAS.

Only in January 2019 the British Museum announced that the number of treasure finds made by the public was at a record height for the second year in a row.

In 2016 detectorists discovered an important Anglo-Saxon settlement.