A Tale of Two Empires: Rome and Persia considers the interactions of two of the world’s earliest superpowers through the prism of their coinages, which they used to promote their power to their subjects and around the world.

As the title suggests, we have tried in this exhibition to treat the two superpowers as equals, not as one against the backdrop of the other, neither does it make an arbitrary distinction between the history of ‘the West’ and the history of ‘the East’. We decided to take a period of history that would be well known, or at least familiar, to a large number of people, and then use it to introduce unfamiliar concepts and narratives. Popular culture has tended to either demonise ‘The Orient’ or silence it, transforming it into an alien, dangerous place. What this exhibition hopes to do is to remove these perspectives, and allow this fascinating period of history to speak for itself. The exhibition is as much a challenge to us today to question and challenge our views of the past, and our conceptualisations of the present.

It is also the case that museums and art galleries are often very old, white and middle class. With A Tale of Two Empires: Rome and Persia, we have attempted to remove the Euro-centrism, and supposition of common cultural reference points by explaining Late Roman Christianity and its expression through coins and seals in the same way that we have explained Sasanian Zoroastrianism – Christ has a short entry on the in-gallery glossary and prosopography in the same way as Zoroaster, Mars like Anahita, etc. In this way we have tried to be sympathetic to the base knowledge and ‘common cultural reference points’ for visitors from an Iranian, Caucasian or West Central Asian background, for whom Shapur I and Khusrau II are household names, as for western European visitors, who are more familiar with the background to the Roman world.

The exhibition focusses on coins, because it is the annual exhibition from the Barber’s coin collection. The Barber has the second largest public collection of Sasanian coins in the UK (after the British Museum), and yet, until now, it has never played a title role in any exhibition. These Sasanian coins are supplemented by the Barber’s excellent Late Roman collection of coins and some beautiful Sasanian gemstone seal stamps, which feature their own captivating artistic devices and are on loan from the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Following the success of The Last Roman: Peasant to Emperor, which focussed on the story of Justinian I, A Tale of Two Empires: Rome and Persia has again tried to make good use narrative, rather than simply presenting objects, and takes visitors on a journey through the story of these two civilisations. After introducing the Roman and Persian worlds, there are three case studies, which tell the story of three flash points in the shared history of the two empires. There are the more traditional yet compelling narratives of betrayal, revenge and war, but also narratives of friendship, tolerance and cultural fusion. The interactions between Rome and Persia through their long histories, as we hope the exhibition demonstrates, were complex and diverse.

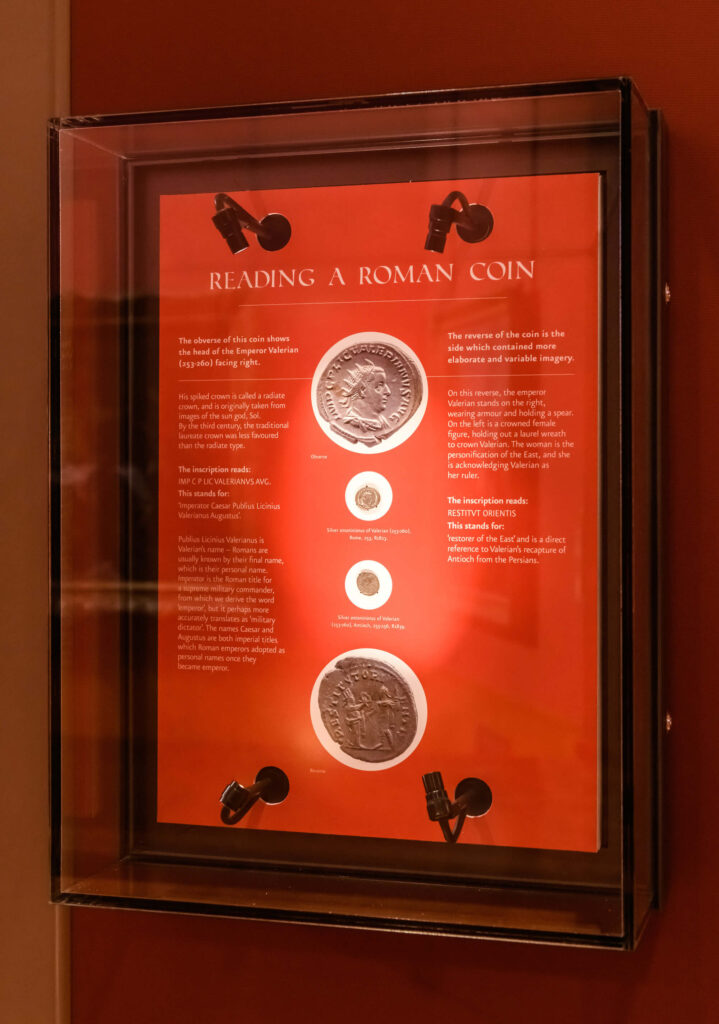

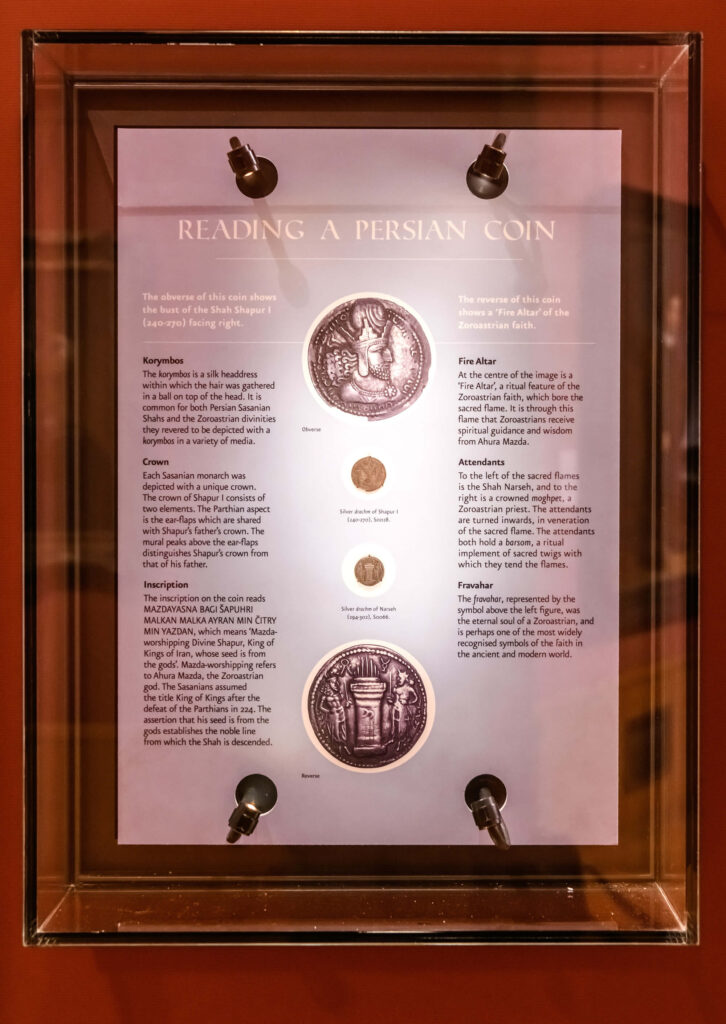

However, exhibitions are, ultimately, about objects – pieces of the past handed down through generations or rediscovered after a long burial. To this end, A Tale of Two Empires: Rome and Persia builds on positive feedback from previous exhibitions by including images of the coins alongside the objects themselves to aid visitors in identifying their features, and two cases by the entrance to the coin gallery, which explain the features on both the obverse and reverse of coins of the Roman Emperor Valerian I and the Sasanian Shahanshah Shapur I.

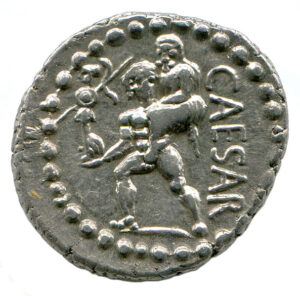

There are many ways to read a coin, however, and the exhibition tries to include a number of relevant points. Economically, the visible change in metal content during the so-called ‘Third Century Crisis’ in the Roman Empire is a microcosm of economic contraction and political instability reflected through coins. Politically, the incorporation of the ‘Fire Altar’ on Sasanian coins reflects both a break from a philhellenic past, and an assertion of a new political and cultural identity, which places the Zoroastrian faith and Middle Persian language at its centre. The reverse of a coin of Philip I ‘the Arab’ spins the conclusion of peace with Shapur I as a positive, while Shapur’s rock relief, used by the exhibition as a central point from which to consider the run up to and aftermath of 260, spins the same peace as a humiliation of Philip before the mighty Shapur. All coins convey in some sense a message, whether it is political, religious, economic or cultural.

The coin collection and its gallery occupy an odd position at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, being a museum piece amidst and art gallery. There are always connections to be drawn between the coins and the art in the galleries, however. These connections could centre upon the artistic quality of an object, but also the historical context of an object, or even a consideration of the perspectives we as a modern audience hold. To that end, the accompanying booklet for this exhibition leads visitors around the other galleries, inviting them to consider elements in the memory and preservation of Rome and Persia in wider art history. The coin gallery exhibition relies upon the extensive coin collection housed at the Barber, but it is the hope of the exhibition that visitors can trace more general artistic and cultural themes that run not only through the ancient world, but that are still relevant to us today. Ultimately, the exhibition sets out to challenge perspectives, of how we view history and its relevance today, of how we view art and what constitutes art, and how we should reconsider our views of the wider world.

For more information, visit the Barber institute’s website.

If you want to know more about the country where the Sasanian capital was located, please read our numismatic diary “Welcome to Iran!”

Claire Franklin-Werz wrote an interesting article about coins of Gallienus related to his campaign against the Sasanians – eurocentric of course.