Who actually has the right to create and issue money? And how has this balance evolved and changed over the course of history? These questions have been given center stage at the latest special exhibition curated by the Bundesbank’s numismatic collection, “Money Creators. Who decides what’s money?”.

Life is increasingly going digital – a development to which the monetary system is by no means immune. New digital forms of money, known as crypto-tokens, have already emerged. This money is being created by individuals and businesses, and increasingly across national borders as well. The Euro-system, too, is talking about a digital euro.

The question now is not only whether money will still be physical in the future, but also, who will be deciding what’s money by then? Reason enough for the Bundesbank to spotlight the subject.

In its 100 m² space for special exhibitions, the Bundesbank goes on the trail of the money creators of days gone by and takes a look at the present day. 300 exhibits – coins, currency notes and traditional payment instruments – have been selected from its internationally significant collection of monetary objects to illustrate the topic. Employing a rich mix of media that includes animations, hands-on stations and a children’s level devised specifically with younger visitors in mind, the exhibition – forged in the studios of Stuttgart-based designers Atelier Schubert – makes for a fresh and varied visitor experience. The exhibition is pitched at the general public and does not assume any prior knowledge. It is fully bilingual (German and English).

A tour of the exhibition

Entranceway: Money creators are individuals and institutions who are able to create and issue money. It is they who decide what counts as money in their jurisdiction. The curators open the exhibition by investigating a key question, namely “What is money?” A mixed assortment of objects provide the answer. An animation explains the traditional functions of money (as a means of payment, a store of value and a unit of account).

Module II: The state as money creator

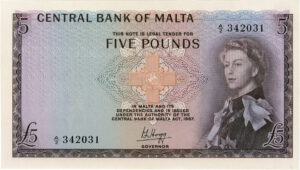

And who are these individuals and institutions behind money? The norm was and is for money to be issued by a state authority. They imprint images or symbols of themselves on coins and notes and sometimes make reference to the source of their authority.

Module III: The state delegates

The past also saw private agents, such as trading companies and banks, issue money. In the 19th century, numerous note-issuing banks existed across the world. There were 33 private banks issuing banknotes in Germany in 1875, for example. Nowadays state central banks have a monopoly on banknote issuance, with very few exceptions.

Module IV: The public money system in times of crisis

A stable monetary system is by no means a given. A government’s failure to maintain a functioning system of cash transactions or to keep the value of money stable entails severe consequences. Barter trade springs up, various forms of emergency and substitute money are born or foreign currencies start being used.

The disastrous hyperinflation of the 1920s is still seared into Germany’s collective memory. The plethora of “Notgeld”, or emergency money, issued by local authorities, businesses and individuals with state authorization or tolerance bears striking witness to those times. The Bundesbank’s numismatic collection holds an almost unrivalled selection of German Notgeld specimens.

Module V: Money without a state

From a monetary history perspective, money issued without a central state authority is the exception that proves the rule. It is a phenomenon often encountered among indigenous peoples – who, however, typically did not use money as an everyday means of payment. It was often used for ceremonial payments, such as dowries or redress when settling legal disputes and was, at the same time, a status symbol.

The phenomenon of privately created forms of money is one we encounter in the present day, too. The most well-known example is regional money, issued by associations with a view to promoting the local economy.

Module VI: Money today and tomorrow

In the final thematic area, the Bundesbank turns to the present day. Nowadays, we choose from an assortment of payment instruments. Central banks – endowed with independence from parliament and governments – like the Euro-system safeguard public trust in the cash and book money of a given currency through their monetary policy. Only time will tell how we will pay in future. But one thing is for sure, the use of money is becoming more digital.

The numismatic collection of the Deutsche Bundesbank

The numismatic collection is stored and cared for at the Bundesbank’s Central Office in Frankfurt am Main. It comprises upwards of 350,000 objects from every era and spanning the entire world. The majority of the items are coins and monetary notes, but it also includes objects which document the tasks of a central bank in respect of cash payments. Highlights from the collection are on show in the Bundesbank’s Money Museum in Frankfurt am Main. A regular roster of temporary exhibitions shed light on topics of current interest. The exhibition is open to visitors Sunday to Friday from 9:00 to 17:00 at the Money Museum and ends on 29th May 2022.

Here you will find further information on the Deutsche Bundesbank’s numismatic collection.

The collection’s inventory of coins, medals and banknotes can be found in the online catalogue.

The last special exhibition of the money museum was about the gold treasures in the vaults of the Bundesbank.