One tends to assume that Turks and Christians were bitter enemies in the 15th century. After all, they were separated by faith. And the Ottoman Sultan Murad II had just – in 1431 – conquered Venetian-dominated Salonika., this was followed by the Battle of Varna 1444 and the Second Battle of Kosovo 1448, where the Ottomans defeated the Christian armies of crusaders. At this time, Murad’s son Mehmet II was probably already dreaming of conquering Constantinople, which was to make him go down in history in 1453. The fall of the Byzantine capital became a symbol of the unstoppable growth of the Ottoman Empire and the historic defeat of Christianity, which was mired in strife.

Christian Artists in the Service of Turkish Propaganda

Therefore, it may seem strange to some of us that Mehmet the Conqueror did not only hire Muslims for the purpose of his self-promotion – he also brought in renowned artists from Italy to present his image to an astonished audience. Likewise, one might marvel at the fact that Christians were willing to glorify a Muslim ruler. However, as is true today: business doesn’t ask questions about faith or political views. When the Venetian Signoria sent its ambassador to the Sublime Porte after the conquest of Constantinople, he was given specific instructions: “Our intention is to live in peace and friendship with the ruler of the Turks.” Of course, otherwise the profitable trade would have declined.

Thus, it was in the interest of Italian city states for their painters and engravers to take commissions from the Ottoman ruler. The most popular of them was probably Gentile Bellini, who not only created the famous image of Mehmet, which is now on display at the National Gallery in London, but also a wonderful medal. The specimen was one of several medals that Mehmet the Conqueror had created as he used the new medium for propaganda just as skilfully as his Christian peers did.

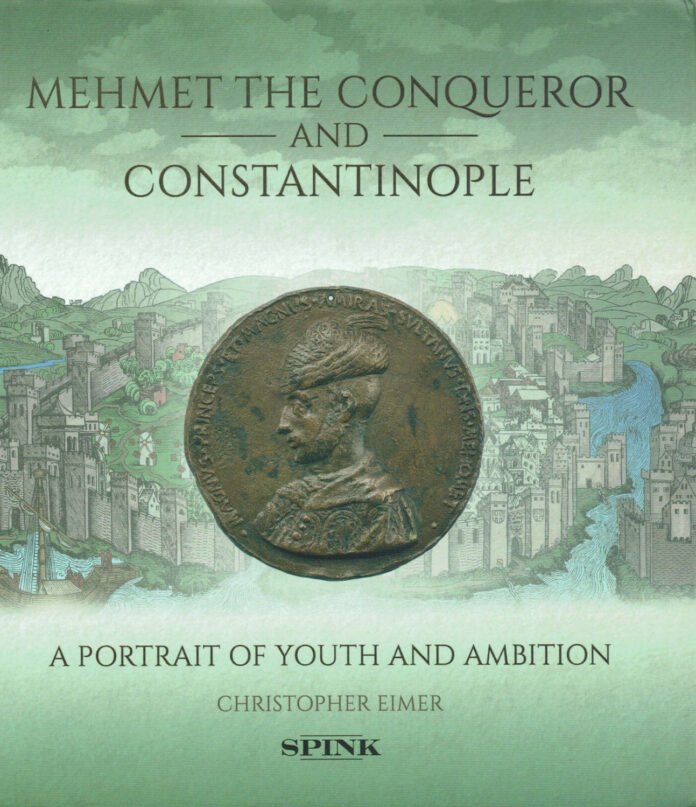

In his book, Christopher Eimer presents a new example for this phenomenon, dating from the early years of the Conqueror. The unique medal was only published in 2000 and its importance was recognised by him when Christie’s sold it as part of an old collection. The portrait of a young man wearing a turban can be clearly identified thanks to the circumscription.

Christopher Eimer dedicated a monograph to this impressive piece, giving it back its history. He meticulously reconstructs the historical and artistic context. In this way, he provides us with a summary of the self-promotion of Mehmet the Conqueror in the Western style.

A Bibliophile Book and a Wonderful Read

If you love books, you will be delighted by Christopher Eimer’s monograph. It has everything a book lover appreciates: First of all, it is a book that is fun to read. It is precisely written and not too long. Including the comments, it’s just 81 pages long. The author attached particular importance to illustrations. They help to understand his explanations. The layout is modest, serving the text and thus supporting the structure of the book. The paper, cover and jacket of the book were chosen with an unobtrusive taste for aesthetics. Briefly put: it is a pleasure to pick up the book.

And one can indulge in this pleasure without a guilty conscience. For the monograph costs as little as 25 pounds, and we recommend the edition to anyone who is interested in the history of the 15th century, in Renaissance medals and / or the Ottoman Empire.

Christopher Eimer’s work illustrates that it is indeed possible to write a readable book that conveys new scholarly findings to a broad public, focusing on a numismatic object and its cultural-historical context instead of the interpretation of literary sources.

The book can be purchased from Spink or from Christopher Eimer, who will be happy to add a brief dedication for the purchaser if desired.