In the 17th century, indiennes – printed and painted cotton fabrics from India – became a popular commodity in Europe. The new temporary exhibition at the National Museum until January 19 2020 displays a number of these magnificent fabrics, tells the story of the textiles’ production, explores their colonial heritage and travels the trade routes between India, Europe and Switzerland.

The Beginning of a Success Story

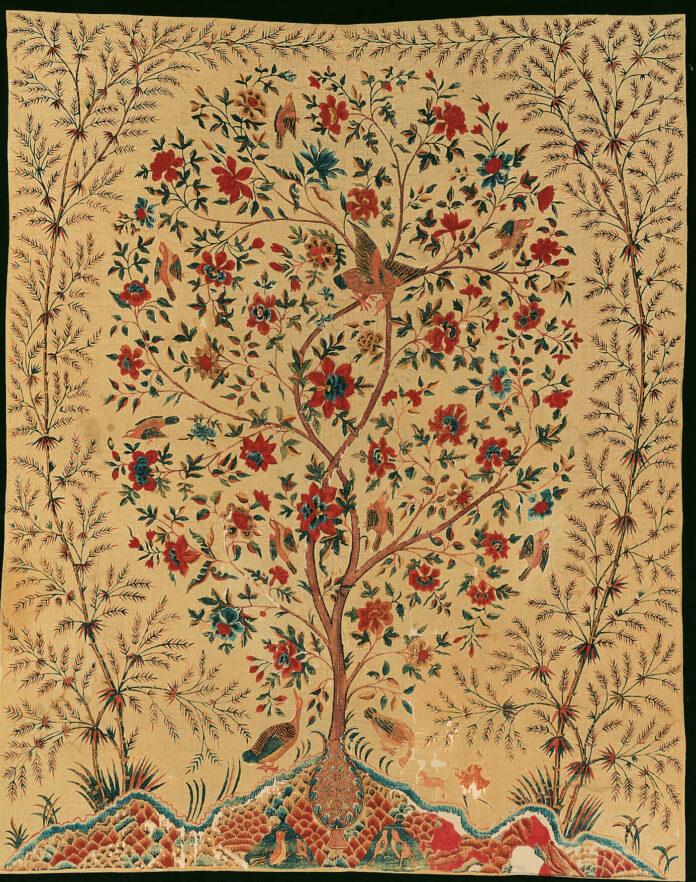

Until well into the last century, cotton was one of the most lucrative commodities in the world. The plant, which grows only in tropical and subtropical regions, was used to produce fabrics which, along with raw cotton, became a major trade product. India played a key role: since pre-Christian times, dyeing and printing techniques had been developed there which for a long time remained inaccessible, and were the paradigm for textile printing in Asia and Europe.

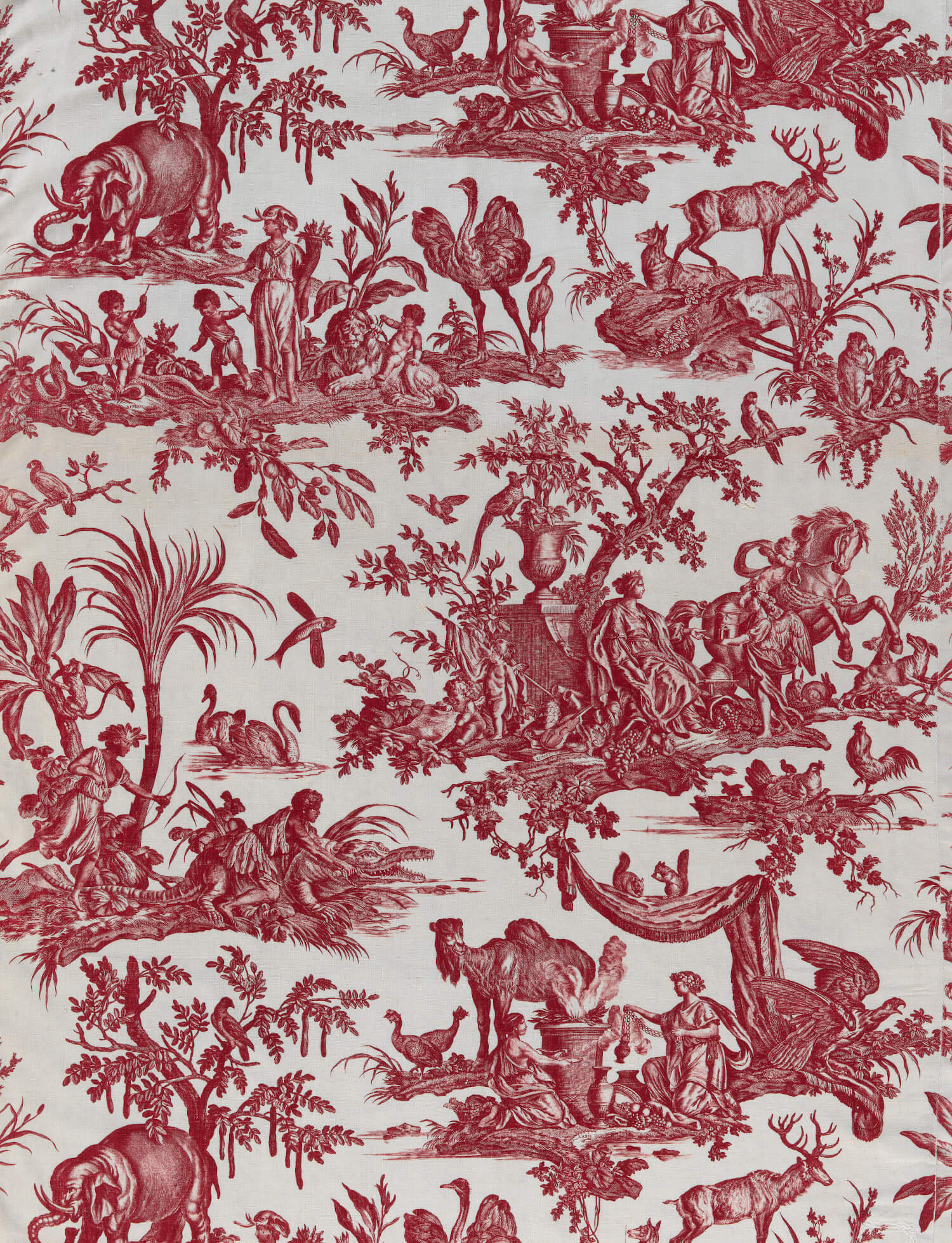

Indian fabrics with unusual motifs, later referred to as indiennes, started to reach Europe from the 16th century. In the 17th century savvy business professionals copied these patterned fabrics, and the following century saw an explosion of interest in them. Western factories, including numerous companies in Switzerland, imitated these precious items and soon indiennes were everywhere.

Indiennes Conquer Europe

The fabrics were used for clothing, curtains and wallpaper or upholstery for chairs and sofas in the homes of society’s upper echelons. The new fabrics were so successful that France closed its borders to protect its domestic silk production. This opened up new opportunities for Switzerland, and soon Swiss firms were heavily involved in trading in the cotton fabrics. For almost two centuries, the unprecedented enthusiasm for these fabrics with their exotic motifs left its mark on the society, economy and fashion of the time.

The Success of European Trading Companies

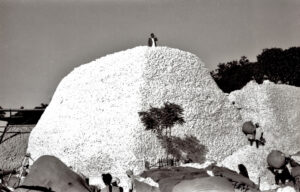

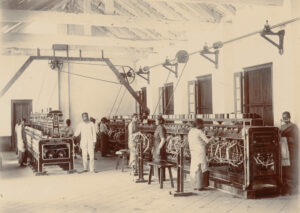

As early as the late 18th century, indiennes industrially-produced in Europe were able to compete, and as a consequence the trade flows were reversed: India’s once thriving textile industry got into difficulties as a result of imports of cheaper textiles from Europe. Unemployment, poverty and hunger became widespread. As of the 19th century, raw cotton was the main product exported for processing in industrialised Europe. Bombay, however, became the centre of the cotton trade, and a separate, rapidly booming textile industry was established. The Swiss trading company Gebrüder Volkart, which would become one of the world’s largest cotton exporters in the late 19th century, established its first branch in Bombay in 1851.

Colonial Life in India

But it was not only businesspeople from Switzerland who were finding their way to the subcontinent at that time. Protestant missionary society the Basel Mission, founded in 1815, sent its missionaries to convert the Indians, who were mostly Hindus. The welfare organisations, hospitals and schools the missionaries set up also had to be financed. Money was brought in with brickworks, printing presses and weaving mills, but at the same time there was fierce debate as to whether it was permissible to generate earnings with the mission.

In the 20th century, cotton again took on a new significance in India. From 1930, hand-spun and hand-woven cotton, known as khadi, became a symbol of India’s independence movement and the trademark of Mahatma Gandhi. Swiss press photographer Walter Bosshard was there, and captured the moment with his camera. His 1930 photo essay shows Gandhi spinning cotton by hand – an early behind-the-scenes glimpse of celebrity homelife. The photos were seen around the world.

The exhibition at the National Museum Zurich presents selected Indian and European fabrics, including beautiful items on loan from within Switzerland and abroad. It also examines how Swiss companies were tied up in the trade in “white gold”, as these highly profitable fabrics were referred to. It’s a story with numerous interwoven threads – an example of how Swiss history is always global history as well.

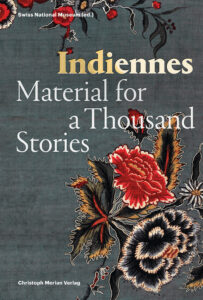

The National Museum published an opulent designed publication bearing the same title and complementing the exhibition. By means of numerous coloured reproductions of masterpieces from both Indian workshops and the prestigious French and Swiss factories, the book highlights production secrets and myths about the thriving and wide-ranging market that made indiennes the first-ever globalised product. The book deals with countless links within Swiss indiennes production.

Find out more about the exhibition “Indiennes. Material for a Thousand Stories” on its website. In this film, you can take a look at the exhibited pieces.