The young Italian state faced pressing problems: a mountain of debts, severe poverty, low industrialisation, poorly developed transportation routes and a high illiteracy rate. Although the nation was largely united, it was deeply divided at the same time.

It soon became apparent that there were irreconcilable differences between the north and the south of the country: a rich, industrialised middle class of the north contrasted with a poor, traditionally oriented rural population in the south. Moreover, Catholics that were loyal to the Pope took virtually no part in creating the political shape of their country because the Pope forbade the faithful to participate in the political life of the secular state.

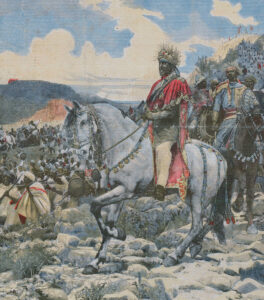

To distract attention from the economic and social problems within the country – and to demonstrate Italy’s new status as a major European power – the Italian government initiated a colonial program and set off to obtain territories in Africa. Initially, the Italian troops conquered Eritrea (1885-1896) and Somalia (1889-1905). However, in 1896 the Italian army suffered an unexpected defeat in an attempt to occupy the Abyssinian (Ethiopian) highlands. This defeat seriously shook up Italy’s position in terms of foreign policy – and the national self-confidence of its citizens. Nevertheless, over time, Italy succeeded in taking over the rule of smaller African territories, not always by means of war but by acquiring them.

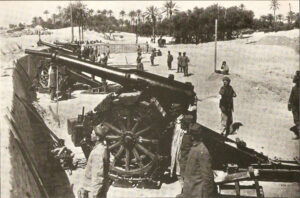

In the fall of 1911, Italian troops marched into Libya, which was part of the Ottoman Empire. This territory was to provide space for the impoverished rural population of southern Italy. The Italian people largely approved of such large-scale projects – they were celebrated as a resumption of the imperial policies of ancient Rome. However, Turkey was anything but pleased about Italy occupying those territories. When Constantinople rejected the Italian request to occupy Libya as they saw fit, Italy declared war against the Ottoman Empire without further ado. By the way, in this war an airplane was used for the first time – the Italian captain Carlo P. Piazza (*1871, †1917) made a reconnaissance flight from Tripoli over a Turkish military camp.

In the slipstream of the Italo-Turkish War (1911/12), the Balkan countries took their chance to rise up against the Ottoman Empire. Faced with this threat, Turkey agreed to a peace treaty in 1912. Italy received Tripoli, the capital of Libya, and the coast of Cyrene as well as some islands in the Aegean Sea. This made at least partially up for the defeat in Ethiopia; the self-confidence of the Italian state got a new boost.

At the beginning of the 1890s, a patch of land changed hands at the Horn of Africa: the Sultan of Zanzibar, who had severe financial problems, sold Somaliland, as the region is henceforth known, to the Italian government for 120,000 rupees. Italy hoped that this acquisition would enhance its domestic and foreign prestige. In addition, the new territory was expected to calm the situation in Italy itself: overpopulation had become a serious problem over the past years and the country was in urgent need of an outlet. Cities were overflowing – 580,000 people lived in Milan in 1910; in 1880 there were only 320,000. Thus, population almost doubled, which inevitably lead to a housing shortage; on average, 3.8 people shared a room in Milan. This made the poor sanitary conditions of the cities even worse. Epidemics such as typhoid, cholera, smallpox and syphilis raged across the cities. Strikes, demonstrations and roadblocks occurred on a daily basis.

The government in Rome hoped to mitigate these problems by creating new settlement areas in Africa. However, it was mainly the poor who emigrated to Africa – i.e. mainly people from the south. Those who could afford it bought a ticket to America, the country of unlimited possibilities. Between 1900 and 1910, more than 600,000 Italians left their home.

To lend weight to its territorial claims, Italy issued coins for African colonies: tallero of 5 lire were minted for Eritrea – in Roman and Milanese mints. From Italy, the coins were then shipped to Africa. In Somaliland, Italian rupees of 8 Italian lire were put into circulation, before the Italian lira became the official currency of the colony in 1925.

In the next episode, we will see how the Italian mafia established itself and how rising the bread price resulted in violent uprisings.

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.