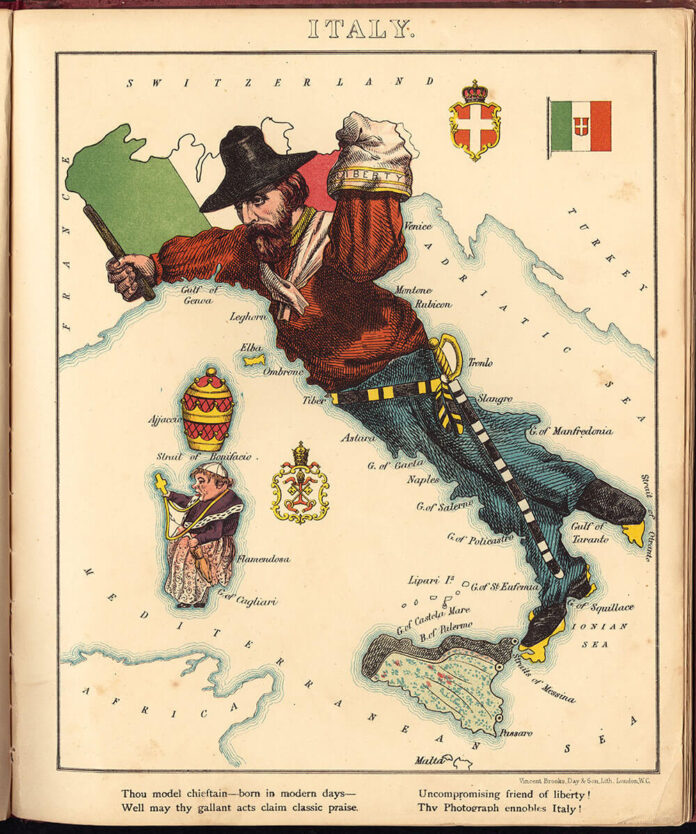

In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi entered the political stage of Italy. At that time, Piedmont had won the war thanks to French help. However, the goal of the war had not been achieved: the Austrians were not completely expelled from Italy, they still ruled in Veneto. And yet – the war unleashed the Italian national movement: referendums initiated by Cavour took place in duchies in central Italy and resulted in the annexation of these territories to Piedmont. In the Romagna and the Legations – the papal territories – unrest was growing. And volunteers flocked from all over Italy to join the Piedmontese army.

Garibaldi and the “Expedition of the Thousand”

On 5 May 1860, the so-called Expedition of the Thousand set out to unite the south and to annex it to northern Italy: 1000 volunteers, most of them intellectual people from the cities, embarked for Sicily under the lead of Garibaldi. There, the Thousand quickly found more supporters. They expelled the royal Neapolitan troops, sailed to the mainland and entered Naples shortly after accompanied by tremendous cheering from the people.

At that point, Cavour also started to advance: he marched his Piedmontese army to the papal territories, and then united forces with Garibaldi and his supporters. In October 1860, Cavour and Garibaldi were able to present the result of the plebiscites of Sicily and Naples to King Victor Emmanuel II, who had rushed over to meet them. An overwhelming majority of the people had voted in favour of the annexation of the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. On 18 February 1861, the first Italian parliament met in Turin and decided to proclaim the Kingdom of Italy. Victor Emmanuel II became the first king of the unified country and Florence its new capital. The Papal States around Rome remained in place for the time being – although they had lost a lot of their territories.

From 90 to 1: Italy’s Lira

Let’s now take a look at the monetary situation of the time. In 1859, about 90 different types of coins circulated in the territory of Italy – a monetary muddle that could only be cleared up with the unification of the country. Therefore, creating a single currency for the new economic area was a top priority. They could either choose to adopt an existing currency or to create a new monetary system – they decided to go with the first option: in 1859, the coinage system of Sardinia-Piedmont – 1 lira = 100 centesimi – was adopted in the entire kingdom.

The lira was first mentioned in Italy in 953 as a coin of account: the name comes from the Latin word “libra” for “pound”. However, they only started to mint actual libra coins in 1472 in Venice, and called them “lira tron”: they were commissioned by the then Doge Nicolò Tron (1471-1474), and the coin’s obverse featured the bust of this gentleman. The reverse depicted the Venetian lion, the Lion of Saint Mark. However, the lira tron soon aroused distrust in the republican circles of Venice – after all, the city-state was a republic and for true republicans the proud doge’s portrait on the coins was too similar to the way contemporary monarchs portrayed themselves. That is why the doge was relegated to his rightful place on Venice’s later lire: he kneels before the depiction of Saint Mark.

Italy Makes Bella Figura with Its New Coins

Following the example of the Venetian lira, several city-states in northern Italy stared to produce silver lire according to various weight standards. We learned already that the lira according to the French weight standard was established in the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont at the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. This is the coin that was adopted by the Kingdom of Italy in 1859. Together with the common currency, the decimal system was also introduced in Italy: one lira italiana was worth 100 centesimi.

By the way, the young state of Italy attached great importance to well-minted coins. Not only silver and gold coins but also the smallest fractional copper issues were designed in a sophisticated style and carefully minted. The image with the king’s portrait reveals nothing about the fact that Victor Emmanuel was a coarse, peasant figure and that his appearance rather resembled a tough steward than a king.

Italy Joins the Latin Monetary Union

In 1863, Italy made another minor change to the lira: the fineness was slightly reduced. A lira weighed 5 grams, exactly the same as a French franc. The gold coins of 10 and 20 lira corresponded to the gold 10 and 20 franc pieces, and the issues of the franc countries – France, Belgium and Switzerland – were also legal tender in Italy. As was to be expected, Italy joined the Latin Monetary Union in 1865.

The Union experienced its first crisis as early as in 1866, when Italy had to introduce a set exchange rate for its paper money due to the costly war against Austria. As a result, Italian silver coinage and even the small copper coins migrated abroad, where they were used as official tender too. In 1893, all Italian silver coins were confiscated in a large-scale operation in Switzerland and sold to Italy. In a vain attempt to return to the metal currency, they were melted down in Italy and newly minted. As early as in 1894, the banks’ obligation to redeem paper money had to be abolished again; Italy’s paper money economy lasted until the First World War.

In the next episode, we will conquer a new capital: Rome! And, of course, this also changes the monetary system of the Papal States …

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.

You can find out more about the Latin Monetary Union in our article “The Gold Standard Part 1: How and Why Gold Became the Most Important Metal for Coins”.