The landmark exhibition “The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East”, which opened March 18, 2019, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, focuses on the remarkable cultural, religious, and commercial exchange that took place in cities including Petra, Baalbek, Palmyra, and Hatra between 100 B.C. and A.D. 250. During this transformative period, the Middle East was the center of global commerce and the meeting point of two powerful empires – Parthian Iran in the east and Rome in the west – that struggled for regional control.

Exhibition Overview

The exhibition evokes a journey along ancient trade routes, beginning in the southwestern Arabian kingdoms that grew rich from the caravan trade in frankincense and myrrh harvested there and used throughout the ancient world. Camel caravans crossed the desert to the Nabataean kingdom, with its spectacular capital city of Petra. From here, goods traveled west to the Mediterranean and north and east through regions including Judaea and the Phoenician coast and across the Syrian desert, where the oasis city of Palmyra controlled trade routes that connected the Mediterranean world to Mesopotamia and Iran and ultimately China. In Mesopotamia, merchants transported cargoes down the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to the Persian Gulf, where they joined maritime trade routes to India. These connections transcended the borders of empires, forming networks that linked cities and individuals over vast distances.

Across the entire region, diverse local political and religious identities were expressed in art. Artifacts from Judaea give a powerful sense of ancient Jewish identity during a critical period of struggle with Roman rule. Architectural sculptures from the colossal sanctuary at Baalbek and statuettes of its deities reveal the intertwined nature of Roman and ancient Middle Eastern religious practices. Funerary portraits from Palmyra represent the elite of an important hub of global trade. Wall paintings and sculptures from Dura-Europos on the River Euphrates illustrate the striking religious diversity of a settlement at the imperial frontier. And in Mesopotamia, texts from the last Babylonian cuneiform libraries show how ancient temple institutions waned and finally disappeared during this transformative period.

A key topic within the exhibition will be the impact of recent armed conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen on archaeological sites, monuments, and museums, including deliberate destruction and looting. Some of the most iconic sites affected – Palmyra, Hatra, and Dura-Europos – feature in the exhibition, which will discuss this damage and raise questions regarding current and future responses to the destruction of heritage.

“The compelling works of art in this exhibition offer a view into how people in the ancient Middle East sought to define themselves during a time of tremendous religious, creative, and political activity, revealing aspects of their lives and communities that resonate some two millennia later,” said Max Hollein, Director, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Further, in focusing on an area of the world that has been deeply affected by recent conflicts and the destruction of sites, monuments, and objects, this show also engages with complex questions about the preservation of cultural heritage.”

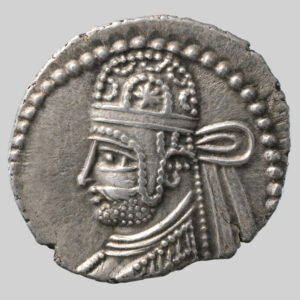

Also the sequence of the many rulers in that region is illustrated by a large choice of coins, partly on loan from the American Numismatic Society.

Mithradates I (r. ca. 171-138 B.C.). From a relatively small state in northeastern Iran, Mithradates I expanded Parthian territory at the expense of the Seleucid Empire, rapidly building an empire that stretched from Central Asia and northwestern India in the east to Mesopotamia in the west.

Mithradates II (r. ca. 121-91 B.C.) consolidated the empire created by Mithradates I (r. ca. 171-138 B.C.) and expanded farther west into Syria. Like other early Parthian kings, he stressed the Hellenistic aspect of his royal identity: his coin portraits show him sometimes wearing a Greek diadem, sometimes an Iranian miter (as seen here).

Under the Roman general Pompey the Great (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus), who arrived in the Middle East with his army in 64 B.C., the remaining parts of the Seleucid Empire were absorbed into the newly created Roman province of Syria, establishing Rome as a major power in the region and bringing the Roman and Parthian Empires into direct confrontation.

The Battle of Carrhae (modern Harran in southeastern Turkey) in 53 B.C. was a key early engagement between Roman and Parthian armies that caused a serious setback to Roman ambitions in the region. Tactically unsuited for fighting the Parthian combination of light and heavy cavalry, a large Roman army, led by Marcus Licinius Crassus against the forces of the Parthian king Orodes II, was badly defeated, suffering enormous casualties.

The first Roman emperor, Augustus, established peace with the Parthian Empire under Phraates IV (r. ca. 38-2 B.C.) and negotiated the return of Roman prisoners of war, as well as the Roman legionary standards that had been captured by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C.

Phraates IV (r. ca. 38-2 B.C.) established a peace treaty with Rome under the emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.-A.D. 14), including the return of prisoners of war and the Roman legionary standards captured at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C.

At times the kingship of the Parthian Empire was disputed, and in this case it is not clear which of two brothers, rival claimants to the throne, is represented. While most Parthian coin portraits follow the Hellenistic convention of showing rulers in profile, some, as here, instead show them frontally.

Trajan campaigned aggressively in Syria and briefly conquered all of Mesopotamia – the farthest east the Roman Empire would ever expand. His conquests were quickly reversed when his successor, Hadrian (r. 117-138), pulled back from much of the territory Trajan had seized, either because he was forced by rebellions or because the new acquisitions would be extremely difficult to defend.

During his occupation of Mesopotamia, Trajan (r. 98-117) installed Parthamaspates, a Parthian prince, as a puppet king. His reign was very brief and entirely dependent on the short-lived Roman occupation.

Vologases III reunited the Parthian Empire following a period of contested rule and fought a major war for control of Armenia against Rome under the co-emperors Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180) and Lucius Verus (r. 161-169).

The younger co-emperor of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180), Lucius Verus traveled to the Middle East to oversee a war against Vologases III (r. ca. 147-191). The focus of this and several other Roman-Parthian conflicts was Armenia, which the two empires vied to make their own client state.

Rome’s Severan dynasty was closely tied to Syria. Julia Domna, the wife of the emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211), was the daughter of the high priest of the god Elagabal in Emesa (Homs) in Syria. She and her sister Julia Maesa played major roles in Roman imperial politics in the early third century. Julia Domna’s son Caracalla (r. 211-217) and Julia Maesa’s grandsons Elagabalus (r. 218-222) and Alexander Severus (r. 222-235) all became Roman emperors: Elagabalus famously attempted to establish the cult of the god Elagabal in Rome.

During its final years, control of the Parthian Empire was contested between two brothers, Vologases V and Artabanus IV (r. ca. 216-224). Both brothers were eventually overthrown by Ardashir I (r. ca. 224-241), a local ruler in southern Iran, whose rebellion marked the end of the Parthian Empire and the beginning of the Sasanian Empire.

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue, suitable for specialists and the general public alike. Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, the book is available in The Met Store.

“The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East” is open until June 23, 2019.

Further information can be obtained from the Met Museum website.

This CoinsWeekly article tells you more about the horrible destruction and looting of cultural heritage in the Middle East in the last couple of years.

In spring 2016, Ursula Kampmann travelled to Iran. In her travel diary reports, she told us, among other things, about all of the fascinating historical sites she visited.

An abundance of articles about ancient coinage, including the Middle East, is available in our archive section.