‘I saw many of my miserable countrymen chained two and two,’ remembered former slave Ottobah Cugoano in 1788, recalling his kidnapping from his homeland in what is now Ghana. ‘…there was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men.’ This was in literal terms what Jean-Jacques Rousseau had decried, more than a quarter of a century earlier, in the figurative sense: that people are born free, and yet are everywhere in chains.

But when, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, the ideas of the Enlightenment philosopher for whom ‘the words slave and right contradict each other’ found their way into the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, they brought neither freedom nor rights for the people stolen from Africa. Far from it. In the year of the Revolution alone, more than 130 slave ships set sail from France’s Atlantic ports – the height of a legitimate trade that was to experience a further upswing in the decade that followed.

People as a Commodity

In the transatlantic slave trade, which had begun with the settlement of Europe’s overseas colonies, people were taken by force from the African continent to the Americas and put to work as non-paid labour on the plantations – mostly sugarcane plantations at first, and later cotton plantations. The financially grasping plantation owners spent little money on feeding and caring for the health of their slaves – if slaves died early, they were easily replaced. On average, a person who started working as a slave on a sugarcane plantation in Barbados in the 18th century survived the hardships of slave life for around seven years.

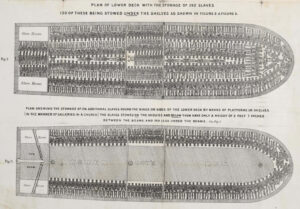

The trade in these enslaved people became part of a triangular commercial arrangement criss-crossing the Atlantic: in Europe’s Atlantic ports, European traders loaded their ships with rum, weapons and textiles – particularly the indienne fabrics from Switzerland and France that had become so popular in the royal courts of Africa. In the ports of West Africa, these goods were exchanged for people who had been brought to the coast by African and Arab slave traders. Crammed like sardines into the ship’s hold and chained together – so they couldn’t jump into the sea and end their suffering – the people were freighted to the New World. From the 16th century onwards, a total of 11 to 12 million people are thought to have been taken. 10 to 15% did not survive the crossing. In the colonies, the slaves were sold and the profits used to buy sugar, cocoa, tobacco, rice and spices – exotic goods that found a ready market in Europe.

Colonial empires such as Great Britain and France were leaders in the slave trade. Scores of Swiss families and companies also invested in the booming business, often making large profits. The Basel-based international trading company Christoph Burckhardt & Cie., for instance, was involved in the inhuman trade through share certificates in slave journeys. A leading player in the trade in indienne fabrics, the firm’s owners also saw, in addition to the direct profit, an opportunity to gain access to African markets by supplying their fabrics to chandlers (ship suppliers). Financial institutions, including the Zinskommission Leu (later Bank Leu), held significant shares in French firm Compagnie des Indes, which had large-scale slave trading operations. At times, 30% of its shares were in Swiss hands.

‘You May Choose to Look the Other Way, but You Can Never Say Again That You Did Not Know!’

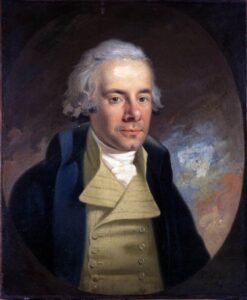

Towards the end of the 18th century, the financial rationales slowly lost ground to the humanist arguments. The autobiography, published in 1789, of former slave Olaudah Equiano played a significant role in this about-turn. The book rapidly became a bestseller, and by the time of the author’s death in 1797 it had run through eight editions. With the story of his brutal abduction as a child and the harrowing crossing to the New World, Equiano gave a face to the ‘person as a commodity’. Spurious justifying arguments, such as the claim that slaves would have a happier life in the New World than in Africa, finally lost all credibility. The glaring contradiction between the values of the Enlightenment and the servitude of the slaves on whose backs Europe was growing so rich could no longer be ignored. In May 1789, in an impassioned speech before Parliament, British politician William Wilberforce presented the first draft of a bill proposing a ban on the slave trade. ‘So much misery condensed in so little room, is more than the human imagination had ever before conceived,’ he exclaimed in Parliament, placing the human tragedy firmly above the economic arguments. But these economic arguments still carried a lot of weight – few people wanted to support a ban on an industry which, despite the risks, promised returns of up to 15%. In France too, people continued to merely pay lip service to the concept of equal rights for all humans: the enslaved people languished in chains while the slave traders in Nantes lived like princes.

Wilberforce would not let go of the issue, tabling new draft laws on an almost annual basis. Eventually his efforts paid off: the prohibition of the slave trade became law in 1807 in the British Empire, and in 1815 in France, with laws prohibiting slave ownership coming into effect in 1834 and 1848 respectively. Slaves in the independent states had to wait longer: after the USA in 1865, Brazil became, in 1888, the last country in continental America to abolish slavery.

The enslaved people had thus finally achieved the freedom proclaimed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and so brutally denied them because of the colour of their skin. However, the exploitation of workers continued: people from India and China soon replaced the slaves. While their obligations were contractually regulated, deceptive recruitment practices, intimidation and violence were commonplace. This form of ‘contractual servitude’ (sometimes referred to as ‘indentured labour’) condemned many to a fate similar to that of the people abducted from Africa so many years before.

This article was originally published on the blog of the Swiss National Museum.

The author Dr Noëmi Crain Merz is a research associate at the Swiss National Museum and a lecturer at the University of Basel. You can read all of her articles for the museum’s blog here.

For more information, visit the website of the Swiss National Museum.

Here you can find an overview of the blog posts.

And if you want to know what the African vendors of human beings asked for the slaves in return, read this article on traditional means of payment.