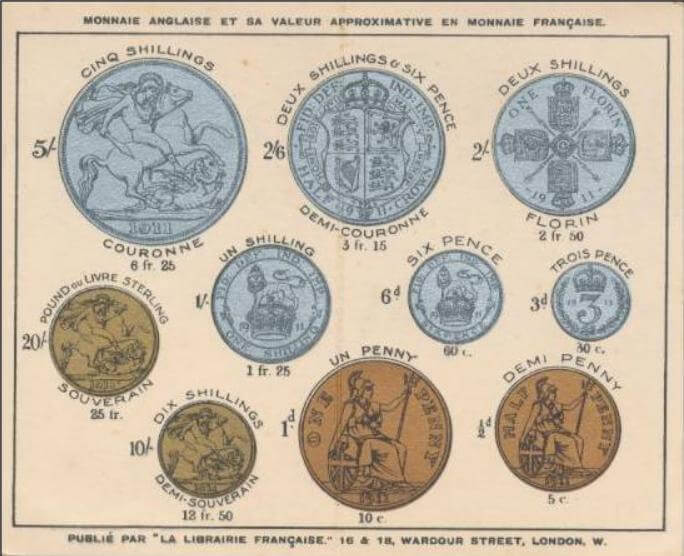

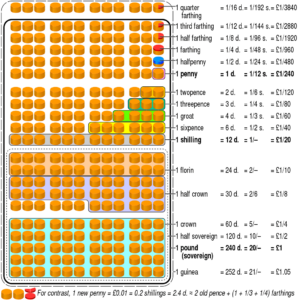

Almost no one remembers it, but on 15 February 1971 a centuries-old British tradition came to an end with the decimalisation of the pound. It was, in fact, called “D-Day” or “Decimal Day” and until that day the British unit of currency had been divided into 240 parts. The smallest unit was the penny (marked with a “d” from the Roman denarii), and twelve pennies made a shilling (marked with an “s” from the Roman solidi), and twenty shillings made one pound sterling. The currency sign of the pound, originally ₤ with two cross-bars, and now more commonly £ with a single cross-bar, derived from the letter “L” (from the Roman librae), continued to be used for pounds, as in the old currency system. From Decimal Day, however, the pound sterling was divided into one hundred new pence. Shillings were now a thing of the past, and “one penny” was now “one (new) pence” and written as 1p (instead of 1d). For many people it was a time of mixed emotions, despite all manner of declarations and calming reassurances the British pound had stayed; but the money – the coins – they had used their whole lives had been withdrawn and taken away from them. So while sterling still had pretentions of being a European and a global currency, the coins that constituted it were all demonetised and replaced by new decimal coins.

“Twelve Into Ten Won’t Go!”

With the change in currency came a subsequent change in language and thinking. For better or worse, many of the old words of the former currency system are no longer a part of the modern English language. As might be expected, the proper terms for a two-shilling piece, the florin, and a five-shilling piece, the crown, as well as the slang for a shilling, the once familiar “bob”, have all but vanished from common use. Similarly, the slang “tanner” for the old copper sixpence has also gone. References to the lower denominations, the small farthing, the halfpenny, or “ha’penny”, and the threepence, “thruppence” or the “thruppenny bit”, actually decreased well before the topic of decimalisation was publicly broached. Thankfully the colourful and popular term for the old pound, the slang “quid”, remains in common use.

The value of the pound was conceived differently, owing to the prices of goods and services that could be purchased with it. In the years just before the introduction of decimalisation two shillings would buy a gallon of petrol; a shilling might buy a small glass of beer; while a few pennies might pay for a packet of chewing gum. My Mum and Dad’s wedding album cost £11/11 or £11-11 (11 pounds and 11 shillings) in September 1963, and my Dad remembers that he earned £13/12/6 or £13-12-6 a month in the Merchant Navy during the late 1950s. After the decimalisation of the pound, however, it was 94p for a pair of women’s stockings, or 29p for a children’s book. The prices of small items never did sound the same again… Of course, this was because the actual purchasing power of the pence was different to that of shillings and pennies, even though the value of the pound remained unchanged. Britain still had its pound, but the monetary values it imparted were now denominated (or constituted) using new coins according to a different logic. Put simply, the number 10 replaced 12 as the base number of its currency system.

Base 10, 16, 20, or 60?

The main argument for the introduction of decimal currency relates to the advantages of 10 as a base number. Arguably made most famous by the Romans, the use of the base number 10 (positional numeral) system has ancient precedents with some of the oldest known hunter/gathering societies (evidenced in Papua New Guinea) having used a decimal counting system (starting with 1, often symbolised by the fore-finger, proceeding to 5, symbolised by the thumb, 6, symbolised by the wrist, going up to 10, symbolised by the shoulder). Moreover, Brahmi numerals, Greek numerals, Hebrew numerals, and Chinese numerals all used 10 as a base number, which is thought to derive from the number of fingers on two hands. Nevertheless, complex mathematical calculations remained very difficult to perform until integers (whole numbers) were represented in the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.

Simply put, our present-day base number 10 system may be seen as the further extension of non-integer numbers (decimal fractions) to the older Hindu-Arabic methodologies. Jumping centuries, if not millennia, the international system of metric Systeme International (SI) units make the decimal system an indispensable, if under-celebrated, part of our everyday lives.

The application of a decimal system to currency, commerce, and finance, however, is not without its own problems and limitations. For example, after “D-Day” six shillings and eight pennies (£0/6/8) was instead written as £0.33. Whereas three lots of six shillings and eight pennies (3 x 80 = 240) equalled a pound, now three transactions at £0.33 each totalled £0.99. Thus, in using the decimal system £0.01 remains unaccounted for (as my big brother liked to point out). Significantly, the number 10 may be divided into halves, fifths, and tenths to give the whole numbers (integers) of 5, 2, and 1 respectively, whereas 12 can be halved and quartered, as well as divided into thirds, sixths, and twelfths, to yield 6, 4, 3, 2, and 1. For mathematicians and almost anyone who buys and sells things for a living, the divisibility into thirds and quarters makes 12 a “very useful number”. Indeed, its functionality surrounds and symbolises us even today. Visit any of the magnificent Gothic cathedrals across the whole of Europe: almost everything you can see and measure has some relation to the number 12, with 3 “the mystery of the faith” being especially important in Christianity.

Indeed, in comparison to 12, the number 10 is quite limited in its utility. From our contemporary standpoint, having a base number that is divisible into integers for thirds and especially quarters (as whole numbers) may seem unimportant, but to many pre-modern societies it was a vital pre-requisite of their base number systems. To get around the problem of quartering 10, the Mayans simply doubled 10 to use 20 as their base number. The Yuki and other indigenous peoples in Central and Northern America used 8, counting the number of spaces between our digits, rather than the digits themselves. In feudal Japan a solution to the same problem was provided by using 16 as the base number of their currency system, as it may be divided into halves, quarters, eights, and sixteenths to yield very functional, whole numbers (integers). Interestingly, the main monetary unit (the ryō) could also be divided into a sub-denomination of 4,000 units for small-scale purchases (but that is history for another time). In a digital world the numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, etc., are still ‘very useful numbers’ with everything from length (in inches, 12 of which makes the next, larger unit) to computer memory (megabytes and now gigabytes) being expressed in these terms.

Bringing the decimal and ‘dozenal’ duodecimal systems together is base number 60 which, of course, comes to us from the Assyrian numerology of our earliest civilisation. A circle – and indeed the globe on which we live – is 360 degrees; an hour is 3,600 seconds (or a grouping of twelve 5 minute periods, with 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness making up a day); and a 360 day financial year (12 months of 30 days, with 5 and a quarter days for calendar-correcting festivals). Our debt to the ancient Assyrians who gave us laws, money, apricots, and so much else, extends to how we use numbers to conceive, measure, and calculate time and space!

Reasons for the “Great Non-Event of 1971”

Returning to the forgotten “D-Day” (lest we completely forget it), we must ask why did it happen in 1971? Through the lens of our 21st century viewpoint, of Brexit, we might link the pound’s decimalisation to the preparations for the United Kingdom’s entrance into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973. It would not be too much of a stretch for some in the UK to blame Brussels, the French, the Germans, the Italians (or perhaps the Romans); but astonishingly, the vital change had been continually under consideration by the Currency Board since 1828. It tells us something profound about the machinations of the British Empire that its financial authorities foresaw the benefits of having a decimal currency system early in the 19th century, but monitored the situation another 143 years before they thought the time was right for reform! The rather laboured explanation for their “change of heart” was the post-war, post-independence, global spread of decimal currencies around the world, and particularly its successful introduction in the former British Dominions of South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Decimal Currency Board was founded in 1964, with Lord (William Geoffrey) Friske as its Chairman, to investigate the possible introduction of the decimal currency system in the United Kingdom. In short order, its findings were presented to cabinet and country as being overwhelmingly in favour of a new decimal system. Its “many advantages” were briskly announced, with the need to conform to the international system of metric (SI) units being paramount. The problem was not framed around shop-keeping or accounting, or business and trade, or even innovation and research in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) as it might be now, but rather about the difficulties of teaching calculations in shillings, pennies, and other sub-pound denominations to children, while also having to teach them the decimal system. In short, the education of children in the United Kingdom was being held back. It was estimated that 6 months of teaching time to primary school students could be saved if the currency was decimalised. And in the background was the growing use of “machine technology” (ahem, computers) throughout the economy, and especially in banking and finance. For example, the Queen Mother had officially opened the Bank of England’s “Computerisation operations” in March 1968.

There is also another critically important, but politically sensitive reason to reform the way in which values less than £1 were expressed that was not publicly mentioned by the Decimal Currency Board: INFLATION! When I heard that my Dad earned £13/12/6 a month in the late 1950s, I thought, “That’s less than half-a-pound (or £0.50 today) a day for chugging around in coal-fired steamships”. A generation earlier, however, front-line British soldiers were paid around 2s (£0.10) per day, minus deductions, during the Second World War. Another generation earlier, and British infantry “of the line” were typically paid 1s (£0.05) per day during the First World War. What that illustrates is that inflation, as evidenced in rising wages and prices, had eroded the pound’s purchasing power (particularly after Britain suspended the gold standard in 1914). So why did Britain’s old coins disappear? It is not just a matter of their base number, but a matter of their monetary value – their purchasing power. As originally conceived the value of a farthing was 1/960th of a pound, a halfpenny 1/480th, a penny 1/240th, a threepence 1/80th, a sixpence 1/40th, and a shilling 1/20th… all small fractions of a pound that were losing their monetary “usefulness” as inflation took hold during the 1960s and 1970s.

And so on 15 February 1971 (coincidently 100 years after Japan) the United Kingdom became the last major country to decimalise its currency system, despite being one of the first countries to consider its introduction, almost 150 years earlier.

Conclusion: on Remembrance and Forgetting

The Chairman of the Decimal Currency is on record as having said if successful D-Day would be the “…great non-event of 1971”. Measured in these terms, the introduction of a decimal currency system throughout the United Kingdom in 1971 was an unqualified success; but success may be measured in many other ways.

Years ago, I came across a fascinating insight into France’s surprisingly conservative experience of using decimal currency and the metric system of SI units, from a French priest who in 1895 was quoted as saying: “Our villagers have passed their military service and our children have [passed through] school but the metric system [from 1791] has not passed into custom yet”. (Quoted from: Ted Wilson, Battles for the Standard: Bimetallism and the spread of the gold standard in the nineteenth century, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p.60, quoting Max Weber.)

This amazed Ted Wilson (from where the quote is cited), for the decimal metric system must surely be one of the most enduring legacies of the French Revolution. The introduction of the new franc in 1803 was supposed to have ground the previous currency systems (with their “outdated” base number 12) into the dust, and yet remarkably in late 19th century France (albeit if only in isolated, rural villages), obsolete coins (liards, blancs, reaux, and old crowns) were still being used by the public, decades after their official demonetisation.

What about in the United Kingdom? Was there an illegal, parallel monetary system, or evidence of any widespread public resistance to the 1971 D-Day campaign? By and large, the changes to the “old money” were accepted as inevitable at a time when many of the time-honoured standards and systems of the British Empire were being reformed, replaced, and relinquished. So while there may have been some nostalgia and fondness for the old pre-decimal system in late 20th century Britain, there was no credible demand, or appetite for its reintroduction. D-Day was a great, if unacknowledged, success. Indeed, today (almost 50 years later) our everyday use of base number 12 and the old coinage that it called into existence: the shillings, the crowns, the florins, the pennies, the halfpennies, and the farthings have been all but forgotten.

Author’s note: I was first encouraged to talk about twelve as being a ‘magic’ or ‘sublime’ number in my research with Mark Metzler, Central Banks and Gold: How Tokyo, London, and New York Shaped the Modern World, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016), p. 205, note 7, thanks again Mark!

In 2013, the Royal Mint remembered the D-Day issuing a coin with the historical design for the new coins of 1971.

To learn more about the author, please read our Who’s who article on Simon Bytheway.