by Annika Backe

December 14, 2017 – The water in the flooded headquarters of the Iraqi intelligence in Baghdad was waist-deep when Dr. Harold Rhode was called to help by opposition leader Ahmed Chelabi in 2003. The building had been hit by a bomb that had not detonate but broken the water system. What seemed unspectacular at first for the experienced Middle East specialist in the service of the U.S. Office of the Secretary of Defense was to have wide-ranging repercussions. Rhode and Chelabi discovered an archive of Jewish documents that has become the focus of a heated debate that between Iraq, cultural experts and the Jews living in the American diaspora.

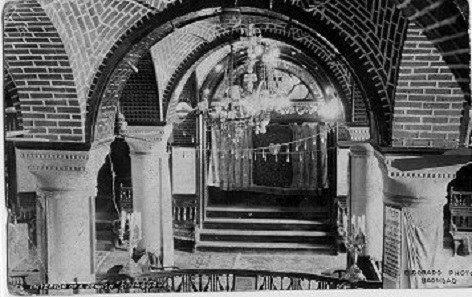

The Great Synagogue of Baghdad, photo in the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Center.

The fact that the archive was found at this site stems from events that occurred another 20 years ago. On behalf of the Iraqi state, documents and liturgical equipment had been seized from the only Jewish synagogue still functioning in Baghdad during a nightly operation in the 1980s. The confiscated objects included 16th and 17th century books, antique Torahs – some of which still in their original containers –, personal photos and much more.

The former owners no longer live in this country that looks back on a long history of persecution and attacks on Jews, with peaks during the time from World War II to the 1960s and again under Saddam Hussein’s regime. The one thing left are the testimonies of their faith and culture.

Torah scrolls continue to be an indispensable element of Jewish services. Photo: Roy Lindman / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Harold Rhode and Ahmed Chelabi planned to rescue the testimonies that formed part of the Baghdad archive. After they had the water pumped out, they realized that many artifacts and writings had suffered considerable damage and thus needed professional conservation. In consultation with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney – and according to Rhodes, in compliance with an agreement that was signed by official Iraqi authorities, the Coalition Provisional Authority and the opposition – the cultural property was shipped to the U.S. for conservation. According to media reports, in 2013 there was a second mutual agreement for an extended five year stay in the U.S.).

Iraq is now insisting on the return of these objects, which were on display during a traveling exhibition in various places in America and touched many Jewish visitors deeply. As for the objects’ future whereabouts, no decision has yet been reached. Observing experts fear a pro-Iraqi solution. After all, the United States have already signed Memoranda of Understanding with as many as 16 countries, Egypt being the most recent one. Following on the notable tightening of import regulations for objects of archaeological and/or cultural value coming from Syria, Libya is currently pressing for a similar codification of its demands. The regulations explicitly apply to objects of Jewish culture as well; experts throughout the world, however, criticize that particularly those countries are currently expressing an increased interest in such objects – or their return, as the Iraq case shows – that are threatening the Jewish owners with reprisals on the other hand.

Several Benin Bronzes, on display in the British Museum, London. Photo: Rtype909 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

This touches on the general question of how nations practically deal with their own history. Do we consider cultural heritage to be the property of the country or of those (minorities) that produced them? Let’s have a look at England. In the venerable university city of Cambridge a dispute has recently arisen over whether or not a bronze cockerel should be returned to Nigeria from its location in Jesus College. The figure is one of the so-called “Benin Bronzes”.

Benin Bronze: Portuguese slave trader surrounded by manillas; the magnificent Benin Bronzes were made from these bronze bracelets. Photo: UK.

These were made from Portuguese metal solely at the royal palace of the Benin Kingdom. The metal came to the royal court in exchange for slaves, as only the King and his licensed slave traders had a monopoly on the trade in slaves with European slave traders. The people whose lives had been bought with this metal were brought overseas as cheap labor, mainly to the U.S. and the Caribbean. That the descendants of these people may also have a claim to the Benin Bronzes is an aspect that gets barely a mention, of course.

Benin Bronze: the King’s local slave agents, holding European manillas in their hands. Photo: UK.

Rather, the focus is placed on the way the Benin Bronzes came to Europe. They used to decorate the royal palace in what is today’s Nigeria. In the 1890s Britain sent an official expedition to Benin under the pretext of stopping Benin’s slave trade with Portugal. Since Great Britain has abolished slavery, politicians have repeatedly exploited this moral high ground to intervene in the political situation of other nations.

The expedition was wiped out by an attack. It has not yet been found out who exactly was behind the attack. Only two men survived. The British government responded by sending a punitive expedition that, thanks to its superior equipment, crushed the belligerent military aristocracy of Benin and conquered the Kingdom. The Benin Bronzes were taken away as reparations for war damage and sold to museums in the western world.

Slaves from the Yoruba tribe, south-western part of modern-day Nigeria. Photo: UK.

The works of art then reached museums all over the world and had a lasting impact on the contemporary notion of Africa. Expressionism, for instance, drew profound inspiration from the magnificent art works from the “Black Continent”.

Today Benin Bronzes can be found in the London British Museum, the Berlin Ethnological Museum and the Metropolitan Museum in New York, to name just a few. The state of Nigeria, which has become independent in 1960, has already made various attempts to get these objects back.

As for the Cambridge cockerel, a permanent return seems to be within reach. As various media report, the University of Cambridge stresses that all museums with Benin Bronzes should aim for a coordinated approach: “Given the scale of the collection worldwide, we believe that collective discussion and engagement will achieve more than independent action.”

Both cases prove how complex the relationship between cultural heritage, the past, the victims, claims, guilt and coping with it, really is. Deciding everything through the nation may be practicable on a legal level, but in no way does it justice to historical developments.

The main information for this article comes from a contribution of the Committee for Cultural Policy from October 2, 2017.

To learn more about Libya’s request for an MOU with the U.S. read this article of the Committee for Cultural Policy.

How private individuals and experts have reacted can be read in this article published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

If you want to learn more about Harold Rhode visit his Wikipedia entry.

The history of the Jews in Iraq is elaborated on here and here.

It is rather difficult to find something on the internet on the complex case of the Benin Bronzes. Highly useful, on the other hand, is an old-school book, the catalog (written in German) “Benin. Könige und Rituale. Höfische Kunst aus Nigeria.” The exhibition was held in Vienna in 2007.

There is, however, a short version available on AncientOrigins.net.

For the return of the Cambridge Benin Bronze read this article in The Guardian.