by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

August 11, 2016 – Iran is a big country. Pretty big. But you only notice how big it really is once you’re on a bus and under the impression that this journey is never going to end. This episode we find ourselves in some sort of Iranian road movie. But don’t worry, the odd tourist attraction lies on our way. We do not only travel many kilometres but also see one city that was destroyed by the Urartians, way too many mausoleum towers, and what is probably the most fascinating relief preserved from Sassanid times – and that means something since there are quite a number of Sassanid reliefs in Iran.

A glimpse of Lake Urmia. (The silver bit on the lower left in the picture.) Photo: KW.

Thursday, 10 March 2016

Sleeping late, that was fantastic. We woke up early enough so that there was still time to cast a glance at Lake Urmia. Or rather the place that used to be Lake Urmia once. Lake Urmia, you must know, is a saltwater lake whose volume is regulated solely by evaporation. Or isn’t. Currently so much water is being taken out of poor Lake Urmia that the lake’s shore has already retracted several hundred meters. Which evidently poses a certain problem to a holiday resort. Our room did have a view onto the lake, just one you needed binoculars for.

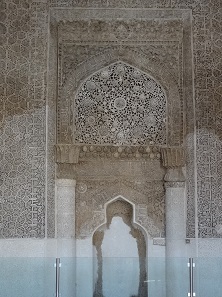

Mihrab of Urmia’s Jame Mosque. Photo: KW.

Our first destination was a mihrab of great art-historical importance in Urmia itself. It dates back to Seljukian times and is located right in the centre of a modern madrasa. A madrasa is an educational institution for Islamic scholars. All those that we’d probably refer to as hard-liners. And that is where, for the very first time on our journey, we met an unfriendly Iranian.

Detail from the mihrab in Urmia. Photo: KW.

The guardian of public morals was not satisfied with the way we had tied our headscarves. While pious Iranian women cover all of their hair with the scarf, less devout Iranian women let it slip back from time to time. Sometimes this reaches a state where the scarf is barely attached to the voluptuous bun at the back of the head. For us tourists, the situation is somewhat different. We simply have no idea how to attach these stupid headscarves in a way that they won’t slip off. They tend to slip off backward all the time. And Cerberus was not at all happy about that. Ranting and raving he hastened towards us from his booth to protect his students from this temptation. Obediently we stuffed our hair back to where it belonged and went to admire the mihrab.

Mausoleum tower, likewise from Seljukian times. Photo: KW.

Our next destination was a mausoleum tower, also from the Seljukian period. A magnificent construction! Which did not interest me in the least. Somehow I seem unable to warm to architecture that doesn’t feature any pictures.

Modern architecture – with a clearly visible Renaissance influence. Photo: KW.

I was much more fascinated by the modern building right next to the mausoleum tower. Somehow Renaissance art had been transformed into concrete. Still it seemed like you could detect the origin of the odd detail.

Artistic detail on the building. Photo: KW.

Let’s take, for instance, this little fellow here, who seems to be twisting a grapevine with an inexplicable gesture.

Thebes. Stater, 405-395. From Künker auction sale 182 (2011), 218.

Doesn’t it remind you of the depiction of Heracles as a young boy, strangling the snakes sent to him by Hera?

Overview of the ruins of Hasanlu as you see them today. Photo: KW.

Anyway. We got on the bus and off we went, driving on a country road. A short two hours later we reached Hasanlu, an important commercial city. Well, important 3,500 years ago. We took a million pictures.

Puppies are cute no matter where you are, also in Hasanlu. Photo: KW.

Yes, some of them even featured the excavation. But the undisputed stars were two cute little puppies, cute enough to be on YouTube.

Walls of the Hasanlu citadel. Photo: KW.

Even if it doesn’t show at first glance: Hasanlu used to be important, if nothing else because the small hill, on which you can see the ruins today, was populated between the 6th millenium BC until AD 300. Archaeologists have divided the hill’s layers into many phases and love it because it offers archaeological proof that even in archaeology there is sex’n crime.

On the topic of sex, there are the Hasanlu Lovers, two human skeletons whose pose has been interpreted as a couple of kissing lovers by archaeologists with a vivid imagination.

And regarding crime: What do you think about the relics of 150 people who have been killed and mutilated? Quite something, isn’t it? People have wanted to connect the bones to the conquest of Hasanlu by the Urartians.

Fortifications of Hasanlu. Photo: KW.

Well, I admit it, I sometimes have difficulty stretching my imagination too far when I’m standing in front of some ruins. So I wasn’t unhappy at all when we finally turned to our picnic. That, however, was remarkable. It did, after all, take place in the courtyard of the local police office. They even let us use their toilet – because there was no other available. We should definitely suggest that to our police, sharing their facilities with passing tourists.

Aaand another mausoleum tower. Photo: KW.

We drove on. And on. I admit that I would have liked to call it a day earlier so that I could finally go on with writing my travelogue, but we still had sightseeing dues to pay from day four, when we hadn’t gotten around to seeing the four mausoleum towers of Maragheh due to a humongous detour on the way to Takht-e Soleyman. Three from the Seljukan period, one from the period of the Ilkhanates. Now don’t ask me which was which. Fact is we saw them all!

One thing that Iran has plenty of is beauty parlours. Photo: KW.

One thing we also got to see on our way to the mausoleum towers was a bit of Iranian everyday life, a beauty parlour. This temple of female beauty was hidden from view by pink plastic film so that no man stood the slightest chance of catching as much as a glimpse. Beauty, I have to tell you, is a big thing in Iran. Even bigger than in Europe. No young Iranian woman with a degree of sophistication would ever be seen in the street without make-up. And those who can afford to get a nose job proudly show this off with a band-aid in the middle of their face. I even heard on the grapevine that this is a status symbol and so much so that some women who cannot afford cosmetic surgery will still wear a band-aid to pretend they can.

The beautiful city of Miandoab late at night. Photo: KW.

It was already late at night when we arrived in Miandoab. I had decided against dinner and for writing my travel diary. An idiotic idea. Which I discarded as soon as we’d reached the hotel lobby.

A look into my room – I’ll spare you the bathroom. Photo: KW.

I remember having occasionally stayed in hotels such as this in my days as a student. The solution is this: Stay at dinner as long as you can, drink as much as you can, at some point you won’t care anymore. Drinking a lot wasn’t an option because there wasn’t a lot to drink. And the restaurant also didn’t qualify as the cosiest of places. Luckily we were too tired to notice much of the room. Undressing before going to bed is overrated anyway, don’t you think?

Still, there’s one thing I need to applaud! Not a single member of our group complained. We all made our jokes but no one started yelling the popular package tourist anthem “I want my money back!” There simply wasn’t a better hotel in Miandoab, end of story.

Friday, 11 March 2016

I was already awake when the muezzin began calling the Muslims to the morning prayer. I’ll leave it to you to figure out why. We got ready in a hurry. Shower? Dream on! The shower consisted of a shower head randomly installed on the wall. When the only water emerging from the tap was red brownish and muddy, I skipped my dental hygiene for the morning.

The dining hall didn’t look much better. A meagre buffet was laid out, cups and plates, forks and knives were still on the trays. No problem, tourists are fast to distribute such things among themselves. Only the tea spoons posed a bigger problem. They were non-existent, so to speak. Sugar was on the table, but how exactly it was to dissolve in our cups remained a mystery. What still kind of works for sugar, doesn’t work for honey. That’s how I sweeten my tea, at home, in Iran, and, if necessary, in the Arctic too. So I insisted on a tea spoon. It only took ten minutes to retrieve two of the demanded items. Quite an unfortunate number. One would have been enough for me. But two were not quite enough for the whole group.

Pictures taken on the bus. Photo: KW.

No one was sorry to leave this place. So we took off. And drove. And drove. And drove. And drove. It felt like forever. Actually it was less than six hours until we arrived at a gigantic hotel that not only looked brand new but had also adapted itself to the needs of Western tourists.

Crossroads are often populated by dealers who sell their goods to those driving by. Here is a cart full of oranges. Photo: KW.

They had vegetables! Even so much of them that everybody could eat to their heart’s content! Should you ever travel Iran and suffer a shortage of greens, I can only recommend the buffet at the luxury hotel Shadi in Sanandaj. And – we were not at all used to this kind of luxury anymore at this point – even the public hotel toilets had toilet bowls designed after the Western model! We were overwhelmed with joy.

And then we had to leave. Again. We drove. And drove. And eventually we had reached our daily quota. Well, not quite yet.

Taq-e Bostan. Photo: KW.

What followed was the highlight of the day, a Sassanid stone relief, which is said to be the best preserved example of Sassanid art.

The great iwan. Dedicated to Khosrow II. Photo: KW.

Truly impressive is the great iwan – and no, I am not talking about a Russ. An iwan is an element of Persian architecture, a type of large niche, like the ones in mosques modelled on the so called four-iwan plan. Imagine a hall with a high ceiling that is entirely open on one side. Got it? Then back to the great iwan of Khosrow II.

Coronation ceremony of Khosrow II. Photo: KW.

On top it depicts the coronation ceremony of Khosrow II: the Sassanid king in the middle, to his left Anahita and to his right Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda hands over a kind of ring, which still makes archaeologists stutter when asked what this thing was supposed to be.

Khosrow, 590-628. Drachm, year 33 of his rule. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 237 (2016), 1573.

Khosrow II is counted among the most influential Sassanid rulers. He came into power after a coup against his father, was, however, quickly cast out by Vahram VI. To win back his throne Khosrow allied with the arch enemy of the Sassanids of all people, the Byzantine Emperor Mauricius Tiberius, whom he promised Amida and Carrhae as well as control over Armenia in return.

Vahram VI, 590-591. Dinarius, Susa(?). From CNG auction sale 100 (2015), 190.

The tactic succeeded. Vahram VI was murdered after only one year in power, Khosrow II crowned once more.

Vistahm, 591/2-597. Drachm. From CNG auction sale, Triton XIV (2011), Nr. 528.

Unfortunately this is not where the story ends. Khosrow had received support from two powerful noblemen, who had of course become yet more powerful after his accession to the throne. That bothered the new king. So he killed one of them. The other didn’t feel like dying – it was to be expected that he, too, was on Khosrow’s hit-list – and sparked a rebellion. Vistahm lived six more years until Khosrow’s assassins were successful and Khosrow comfortably back on top again.

Phocas, 602-610. Solidus, 604-607. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 233 (2015), 2784.

Let’s take a look at the Byzantine Empire, where, in 602, Phocas had Mauricius Tiberius murdered after the coup against him. Khosrow took this as the end of their contract. He went to war, of course only to revenge his friend Mauricius. And along the way he also recaptured those territories he’d once given the deceased for his help. And a few more.

Heraclius, 610-641. Solidus, 610-613. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 237 (2016), 2215.

The tide turned with the accession to the throne of Heraclius. In 627 Heraclius won the Battle of Niniveh and threatened to lay siege to Ctesiphon. Khosrow II took flight.

Kavad II, 628. Drachm, Susa. From Peus auction sale 416 (2016), 151.

And that was when the hour had come for Kavad to enter the stage. He was Khosrow’s oldest son who had until then lived in captivity since Khosrow had wanted to anoint someone else his successor. Kavad was supported by Khosrow’s enemies, escaped and had his father killed. Afterwards he made peace with Byzantium and would probably have lived a long and happy life had it not been for the pest, which carried him off only months later.

Wild boar hunt. Photo: Sigrid Hodel.

In Taq-e Bostan Khosrow II is a star, not because of the coronation relief but because of the reliefs along the sides of the iwan, which depict scenes from Sassanid everyday life – well, if you can call a king’s life ordinary. The most important scene is the boar hunt. Please note all the elephants, which drive the piglets toward the king.

Wild boar hunt. Detail. Photo: Sigrid Hodel.

Who is standing on a boat, surrounded by female musicians so that no piglet could come close enough to do him any harm.

Wild boar hunt. Detail. Photo: Sigrid Hodel.

After all, the boars are pretty treacherous and dangerous with their short tusks, which is quite visible in the relief.

Wild boar hunt. Detail. Photo: Sigrid Hodel.

The wealth of detail is adorable: Here you can see several servants discarding a wild boar in order to carry the meat into the royal kitchens.

And I’ll call it a day here. Our next episode will lead us deep into the Persian Empire, to Bisotun and Dareius the Great, and to the ancient royal city of Ecbatana. If only it hadn’t been so hot there …

You can find all episodes of the Iranian Diary here.