by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

May 26, 2016 – Did you know what autocephalous means? An autocephalous church is one that is its own rule-giver. The Coptic Church, for instance, is autocephalous because it is said to be founded by an apostle, Saint Mark. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople functions like an honorary president of the Orthodox Church since Saint Andrew was the first bishop of Constantinople according to the written records. The Pope traces his honorary position back to Saint Peter. Well, and the Armenians have Jude the Apostle, also known as Judas Thaddeus, whose tomb in the St Thaddeus Monastery, the Black Church, we will visit in this episode.

But our first destination is Ardabil, where the founder of the Safavid dynasty is buried. Perhaps contrary to your expectations, he was not a powerful ruler but a Sufi, a kind of Muslim mystic.

Clay brick villages against a magnificent mountain landscape. Photo: KW.

Tuesday, 8 March 2016 – Continuation

It took us three hours to Ardabil. The drive was incredible! We were moving at an altitude of an estimated 1500 m. On the horizon, to our left and right, we could see the snow-capped mountain tops. Our hopes of catching a glance of the Caspian Sea went up in smoke when we heard that we were separated from it by a good 80 km distance and a mountain range.

The Iranian version of a self-service restaurant. Photo: KW.

We reached Ardabil at 2 pm and were carried straight to lunch. That is, we would have been carried to lunch had Ehsan found the restaurant. You could watch him get more nervous by the minute. He didn’t understand the local variation of Farsi! Ardabil is very close to the Turkish border in the Iranian part of Azerbaijan. And it sounded very Turkish around here, claimed Ehsan. So we kept walking up and down the main street, turned into a residential area, and back to the main street. And eventually we were back to exactly where we had started only to realise that the restaurant was just across the street.

Still, it was worth every meter of the detour. The restaurant was filled with locals. The men were sitting on chairs at the tables, women and families were lounging in carpeted niches at the fringe of the room. And yes, believe it or not, there were numerous groups of women without male company!

The bar parlour was dominated by a huge self-service counter, a combination of some kind of fast food and take-away. There were salads, kebab, meat in special sauces and – once again – no vegetables. Iran is not a country for vegetarians, at least not when you’re bound to eat at restaurants: It goes without saying that, in restaurants, you eat the best and most valuable the Iranian cuisine offers and that means exclusively meat dishes. Do I have to even mention that it was delicious? The Iranian cuisine is famous for a reason.

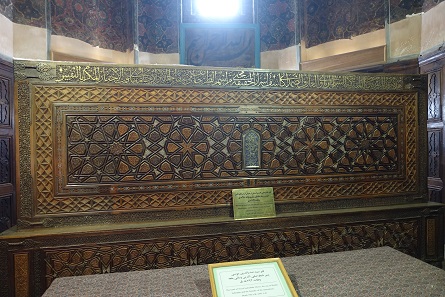

Burial monument of Sheikh Safi-ad-din. Photo: KW.

Reluctantly we left the restaurant to visit the splendid burial monument of the Safavid dynasty’s founding father.

The shrine of Safi-ad-din. Photo: KW.

Many European dynasties once proudly boasted of having holy kings among their ancestors. Sheikh Safi-ad-din, name patron of the Safavid dynasty, was worshipped as a Shiite saint already by his contemporaries. He was a Sufi, a kind of Muslim mystic, someone who searches God in his very own way. You don’t become a Sufi without help. You have to go through a comprehensive training. Safi-ad-din became a disciple of the famous Sheikh Zahed Gilani. He became his favourite disciple and, since Sufis are allowed to marry, was given his teacher’s daughter for a wife as well as the control over Gilani’s Sufi order.

As is usually the case with free spirits, the Sufis were not exactly favourites of the Islamic clergy. That’s why Safi-ad-din fled to Ardabil and there founded a new monastery. Under the name Safaviyya his order became known and famous and … rich, yes, also the Muslim versions of Christian monasteries attracted plenty of donations.

Mausoleum of Ismail I. Photo: KW.

Safi had several sons and they in turn had several sons and one of them rose to be the Shah of Persia. But I’ll tell you more about that once we get to Shiraz. Anyway, so the first Shah of the Safavid family was buried where Safi-ad-din already lay, and that turned the once humble Sufi sanctuary into a national treasure that each Shah of the Safavid dynasty, accompanied by his entire royal household, would visit once a year to commemorate his ancestors.

Mausoleum tower of Safi-ad-din. Photo: KW.

You cannot imagine the splendour of this mausoleum. Let’s take just the mausoleum tower which rises above the cenotaph of Safi-ad-din. It is preciously decorated with tiles which carry nothing but the name of God. How highly symbolic this is: for the faithful, God remains the most precious decoration of all (even though it took an artistic calligrapher, the exquisite craftsmanship of a bunch of craftsmen and, last but not least, a ton of money to manufacture this “simple” decoration.)

The whole building complex was raised to the status of World Heritage Site by the UNESCO in 2010. And still we were – once again – the only tourists. Not a single visitor was to be seen in the large square, in which one souvenir shop is to line up to the next soon. So far, most of the shops aren’t even rented out yet.

A look into the prayer room. Photo: KW.

The beautiful interior of the mosque is made up of several connected rooms. You first enter the actual prayer room, richly decorated, the contours of the wall paintings lined with subtle stucco work. The entrances and openings are exquisitely designed and also matched the floor until the 19th century.

To cover the floor, the Safavid rulers had commissioned a huge carpet that did not only take up the mosque’s ornamental decorative pattern but – being made of one piece – exactly covered the entire mosque. Today the carpet is exhibited in the Victoria & Albert Museum. It must have caught the attention of an English art connoisseur and due to very common practise of “exporting” goods in the colonial era became the world’s most famous carpet. There are countless copies of this type, all called “Ardabil”. One of these Ardabils once adorned the floor of Adolf Hitler’s Berlin office – not quite the best recommendation for it. And even today the British Prime Minister in 10 Downing Street looks down on a reproduced Ardabil.

Almost like a room in a baroque Bavarian castle: the Porcelain Cabinet. Photo: KW.

A porcelain chamber served as a representative festive hall for the Sufi monastery. Yes, correct, like the baroque German porcelain cabinets: A large circular room with many niches and shelves, which was still filled with precious china until the third Persian-Turkish War (1804-1813). Some among the Russian officers were obviously able to recognise a valuable object of art if they saw one, and moved the best pieces to St Petersburg, where they can still be seen today.

It had gotten late again when we arrived at the hotel. But hey, we have to get up earlier again tomorrow. The bus takes off at 7.30. That means getting up at 6.00. And some people like to call that a holiday …

Quick stop on the way. A beautifully restored caravansary. Photo: KW.

Wednesday, 9 March 2016

Wide awake? That was not something I was feeling when I crawled out of bed and into the bus at 7.30. We had a good three-hour drive before us to get to the St Thaddeus Monastery, the Black Church.

Mount Ararat. Photo: KW.

After a few hours we were utterly surprised to see Mount Ararat, which is technically on Turkish grounds, but so close to the Iranian border that you get an excellent view if the weather is good. And the weather was good. Ararat rose up against the sky in all its splendour: snow-capped, against a clear-blue sky.

With 5137 m the (great) Ararat is Turkey’s highest mountain. The “little” mountain next to it is called – surprise – “Little Ararat” and still makes it to 3896 m (by comparison, Germany’s highest mountain, the Zugspitze, is 2962 m high, the Austrian Grossglockner 3798 m; the Swiss Matterhorn at least can boast of its impressive 4478 m).

Those well versed in the Bible (well, the Genesis) know that Mt. Ararat is commonly linked to Noah’s Ark which ran ashore after the great flood.

Coat of arms of the Democratic Republic of Armenia (1918-1922). Source: Wikipedia.

Despite angry protests on the Turkish side, Ararat remains an Armenian symbol, which was even depicted on the escutcheon of the coat of arms of the short-lived Democratic Republic of Armenia. After all, the Armenians had settled around the Ararat before the genocide drove them out of their homeland.

Armenia. 500 Dram 2012. Noah’s Ark. From Rauch E-Auction sale 17 (2015), 922.

In 2001 the Armenians celebrated 1700 years of Christianity in Armenia as it must have become state religion under King Tiridates III in 313/4. That makes Armenia the first Christian empire in history. And the records of the Old and New Testament are still perceived as salvific history today, which may be the reason why this bullion coin, manufactured by a German company and issued by Armenia, features Noah’s Ark.

Livestock transport – Persian style. Photo: KW.

Mt. Ararat came as a big surprise to us. Everyone stormed out of the bus to take dozens of pictures. It was cold. It was solitary. And still there were other things than the Ararat to be seen, for instance this Persian-style livestock transport.

The Black Church, where Jude the Apostle is supposedly buried. Photo: KW.

By 12.00 we had arrived at the Black Church. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and will some day probably belong to the three-star sights that you just have to see. Right now it is still an insider tip. The large building that was put up to sell entry tickets and souvenirs remains vacant. The silence here in itself could qualify as a tourist attraction.

Dung as fuel, stacked to form a walk-in hut. Photo: KW.

Not to mention the adjacent village, something of which Europeans would like to believe that it doesn’t even exist anymore. The villagers live in clay houses, which are not that different from the ones that were built round about 9000 years ago in Catalhöyük. Some are modern and have their roof sealed off with a shiny silver foil instead of letting it grow over with grass as it is done traditionally. In front of the houses are huge dunghills and behind the houses dung is beaten into flat, round pieces and left out to dry. In a country with sparse forests that is the ideal and the cheapest fuel.

The oldest part of the church is built from black stone. Photo: KW.

St Thaddeus Monastery is the major sanctuary of the Armenians. It is said that Jude the Apostle founded the world’s first church here in the year 66. Well, at least we have actual written records that point to the existence of the monastery from the 5th century.

Ecclesiastical history doesn’t know much of Jude the Apostle; theologians even discuss whether the historical figure could have been a mixture of several different people. His attribute, a club, speaks of his martyrdom that is written down in the Legenda aurea: Jude the Apostle went to Persia with a companion, where they converted the King of Babylon and many of his courtiers to the Christian faith. But heathen priests were afraid to lose their influence and beat Jude the Apostle to death with a club.

The part of the church built from white stone in the 19th century is covered with the most delicate relief works. Photo: KW.

The Armenians, on the other hand, say that Jude the Apostle, together with Saint Bartholomew, came to Armenia and there founded the Armenian Church. According to tradition a hermit found his remains and saw to it that they were entombed in the monastery that Jude had founded.

There was just enough snow in front of the church for a few snowballs. Photo: KW.

The church is lovely from the outside. It is made up of two parts: One is seemingly unimpressive, black, with few geometrical ornaments. The construction of this part was begun in the 14th century, immediately after the first church had collapsed. Added in front of it is a larger nave from the 19th century with beautiful frescoes which trail the walls all around the church. Weaved into the vegetable-like garlands are delightful little scenes: the leviathan, a cross between whale and elephant, a couple of lovers in tender embrace, fighting knights and many others.

A look inside the church. Photo: KW.

The church itself is rather small and empty. But not all year round. Armenian Christians from all around the world gather here to celebrate the feast day of Jude the Apostle. Oh how I’d love to witness that myself! They build a tent city in this deserted area, decorate the church with liturgical items and celebrate their pilgrims’ mass.

Picnic in front of the church. Photo: KW.

We had a picnic next to the church. I know it is really hard to imagine in this world today but there was no beverage cart, no restaurant, no nothing at this UNESCO World Heritage Site. Not even enough tourists come through here to make a postcard stand lucrative.

The village Bastam at the foot of the Urartian fortification. Photo: KW.

Afterwards we headed to Bastam, a Urartian fortification. Although I personally thought the village at the bottom of it was much more interesting. We marched past several farms, made of clay and arranged in a rectangular shape around a courtyard. A cow was milked at one of the farms, at another one the rounded up cattle was awaiting us and everywhere small children were staring at us with big eyes.

Plastic: a bane. Photo: KW.

But let’s not get overly romantic in view of this idyll. Bastam, like many other villages in Iran, has a real waste problem. The creek that runs through the village is just one little example of that. It is filled with waste. And don’t think that is an exception! I have never seen anything like it in my entire life. Everywhere in Iran there are meadows and fields, nature in its purest form (you would want to believe), and they are littered with countless plastic bags. Waste is literally omnipresent unless you enter a city. Those are clean. Every city-dweller naturally gets rid of his waste in the next litter bin. Each cigarette is carefully taken to the bin. But once you get to the countryside, the place is just covered in empty crisp packets and plastic bottles.

The most attractive part of the ruin of Bastam. Photo: KW.

Leaving this aside, we walked across the village to the excavation’s back entrance, which isn’t really an entrance but rather a hole in a fence through which all members of our party squeezed one after the other. We were followed by a tail of the village youths. At first there were only one, two little boys. But they just kept getting more and more. They excitedly screamed “money” and “photo”. Not that this was intimidating or threatening but still more of them appeared. And they were a tiny bit importunate. Their good manners seemed not to apply to Western women. When I didn’t want to take a picture of them they barred my way so that I would have had to go round them on pretty uneven ground. Which, of course, I didn’t. I pushed through them, with body contact. Something they were uncomfortable with. Something that humble Iranian women don’t do, after all. And after that they left me alone. (Which may also have been because I only moved in the protective proximity of a man from then.)

Entrance to the Urartian fortification. Photo: KW.

Let me say a few words about the Urartians. They lived in an extremely mountainous area, first around Lake Van. Their capital was called Tushpa and was located where the modern Van is today. Its name first appears in Assyrian records from the 13th century. Of course the Urartians tried to expand their empire. They made it until Lake Urmia, about which you’ll read more in the next episode. Bastam was one of their border fortifications.

Several inconsequential Urartian fortifications. Photo: KW.

And that is not untypical. Most settlements that we know of from the Urartian Empire were fortifications. They served as administrative centres, religious centres and storage facility. In war time the farmers from the adjacent villages could seek shelter behind the walls.

We, too, sought shelter in our hotel. It was at most quarter past seven when we arrived in the holiday resort next to Lake Urmia. During this season we were the sole guests, which had a pleasant side effect: The kitchen staff, unfortunately, could serve breakfast at 8.30 only, which means that we had to get up as late as 7.30! Heavenly!!! I am definitely for the introduction of unions in all Iranian hotels!

Our next episode leads us to yet another Urartian fortification as well as to plenty of mosques and mausoleum towers. But then we’ll (finally) arrive in the Persian-Parthian-Sassanid period. We will see the relief of the great Dareius I, the Parthian temple of Anahita in Kangavar, and the Sassanid high-relief Tag-e-Bostan. Yes, we’ll even make it to ancient Ecbatana. But please don’t expect too much of the latter.

You can find all episodes of the Iranian Diary here.