by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

April 7, 2016 – Forget everything you thought you knew about traffic in the Middle East. It’s different in Iran. As soon as you reach the highway large billboards ask you to fasten your seatbelt. We counted four speed cameras on the 180 km long way from Tehran to Qazvin – three fixed installations and one flying up in the air (and I am sure we didn’t even notice the camouflaged ones). Our driver had to contact the police every few hours to show his tachograph. And when his driving hours exceeded the number of permissible hours per day, a second driver would suddenly pop up at a random intersection and take over for a few hours.

So traffic regulations are taken extremely seriously on the highway. Once you cross the city limits, however, the rules go out the window and you’re back to survival of the fittest. Everyone makes his own rules. Traffic regulations? For weaklings only!

Road markings? More like orientation points. When stuck in traffic, lanes can be extended at will. Unless you prefer to just park your car on the middle lane. If there’s no getting through anymore, at least a motorcycle will always squeeze through somewhere, if necessary on the pavement, the roofed bazaar or the courtyard of a mosque. And those motorcycles are quite something. They can carry up to 4 people and are overburdened with tons of goods of all sorts.

Saturday, 5 March 2016

The Azadi Tower (= Freedom Tower), a landmark of modern Tehran. Photo: KW.

So in the eyes of the Iranians unknowing tourists are unable to cope with their traffic. That’s why we had strict instructions to take photos of the Azadi Tower from the side of the road only. And I have to admit, I almost found the rushing traffic more fascinating than the tower itself. Reza Shah Pahlavi had it built on the occasion of “2,500 years of Iranian monarchy” – oh well, I guess every monarch writes history as he pleases. Only eight years after its completion, after the Revolution of 1979, it was renamed Freedom Tower.

And just like that we are right in the middle of the history of modern Iran like I promised you last week.

Mohammad Khan Qajar, 1750-1779. Half toman, Qazvin, 1792/3. From CNG auction sale 369 (2016), 623.

Although the first mention of Tehran in writing is from AD 942, only the Qajars made the city their residence. There was so much bloodshed in the early history of this dynasty that I am surprised Hollywood hasn’t turned it into a film yet. (Most likely because in Hollywood – like in the rest of the world – people don’t know a whole lot about Iran’s history.)

Under Safavid rule, members of the Qajar upper class traditionally held important administrative offices in Azerbaijan. So did the father of Mohammad Khan Qajar, whose story we will sum up here for you. Daddy was disposed from his office, started a rebellion, failed and was executed. During one of the battles, young Mohammad, only four years old, was castrated so as to get rid of him as a potential enemy. He lived in captivity for 16 years.

When he managed to escape, he started – surprise! – a rebellion. He was, however, more successful than his father. He conquered the whole of Iran. The cruelty which he used became legendary. But, let’s be honest, how cruel would you be if you had been castrated as a four-year-old only to live in captivity for the next 16 years?

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, 1797-1834. Toman, 1815/6. From Künker auction sale 256 (2014), 6890.

He made Tehran his capital since the city is further north than the traditional centres and thus closer to the Qajar power base in Azerbaijan. And Tehran remained capital even under Mohammad’s successors.

Historically we are now in the 19th century and the European powers are fighting for the supremacy over different parts of the world. Russia was especially dangerous for Iran. After all the two countries shared a common border and many tsars, among them Peter the Great, had gone to war with Persia.

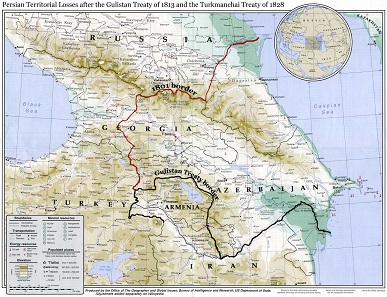

Persian border according to the Treaty of Gulistan. Source: Wikipedia.

Peter conquered four Persian provinces; due to the Treaty of Gulistan from 1813 the Persian Shah lost the provinces Georgia, Armenia, and, north of the Aras, Azerbaijan. The treaty remains one of the severest humiliations in the history of Iran.

Nasir al-Din, 1848-1896. 1 toman, 1895, on the occasion of his 50 years in office jubilee. From Künker auction sale 261 (2015), 5987.

Of course there was also a reform movement in Iran. Attempts were made to keep up with the West by slowly modernizing. But all efforts were in vain. It was too comfortable for the Shah and his closest advisers to lean back and leave things as they were, to their personal advantage.

That worked by way of granting concessions: Foreign investors helped the Shah exploit his subjects yet more effectively. The Shah (and a few intimate friends) received a substantial share.

Nasir al-Din gets into his saloon carriage after visiting the Krupp works on 16 June 1889. Source: Wikipedia.

So in 1890, for instance, Nasir al-Din sold the monopoly for the import and export of tobacco to a British officer. The English were giddy with excitement about this. They were expecting an annual revenue of 500,000 pounds. They generously promised 25% of the revenue to the Shah. But this time he had gone too far. Too many people suffered from the impact of the trade agreement. Tobacco farmers were dreading the price decline; local dealers lost the handsome profits from the daily tobacco trade; and consumers had to expect higher prices.

Suddenly a new fatwa was being circulated: “From this day onwards, the consumption of tobacco is considered a declaration of war against the Twelfth Imam.” A fatwa is a legal opinion. And Islamic jurists have always had a big influence on Shiite Iran, especially when they said what everyone believed to be right anyway. Not much later, a second appeal was in circulation: “The jihad will begin on Monday. Be ready.” And the Shah got cold feet: He ended the monopoly and compensated the officer with 500,000 pounds for his loss. Five years later Nasir al-Din was dead. Assassinated.

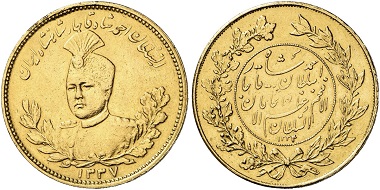

Ahmad, 1909-1925. 10 Toman. From Künker auction sale 260 (2015), 2045.

I could tell you many other depressing details. They all talk about greed, uneven power relations, poverty and humiliation. To cut a long story short: the Qajar rulers became weaker and weaker. The British became more powerful. They even tried to turn Iran into a British crown colony after World War I.

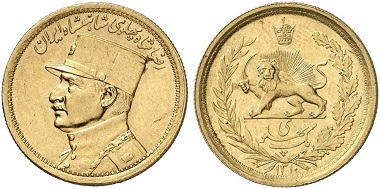

Reza Shah, 1925-1941. 1 Pahlavi 1931. From Künker auctions sale 251 (2014), 3281.

Of course that called for resistance and that resistance came from the military. In fact events in Iran unfolded not much differently than in Turkey. Both states felt their national independence was threatened. In both states a high-ranking military officer took the initiative. In Turkey his name was Mustafa Kemal, in Iran Reza Khan. In 1925 this Reza Khan overthrew the last Qajar and declared himself his successor.

What happened next could almost be a blueprint of the reforms that Atatürk implemented in Turkey: traditional clothing was done away with, reforms were made in administration, education and the judiciary system, the economy was modernized. No, wait a second, the economy. Iran was and still is one of the most important oil providers worldwide and that means national agendas were involved. A national agenda of the British because they owned 52.5 % of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Iran received – and that is just an example – a mere 10 % of the profits from the petroleum industry in 1923 …

Islamic Republic. Azadi 1991. From Künker auction sale 269 (2015), 6630.

I am certainly not going into the reasons that led to the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Other, notably better informed, authors have done that before me. But I think that, in view of the current re-islamisation that is taking place, and the fact that modern-day Turkey is reversing Atartürk’s reforms one by one, the question is justified if some things that happened after World War I weren’t done too quickly and for the wrong reasons.

Entrance to the Jameh Mosque of Qazvin. Photo: KW.

But enough of that. Back to Iran, more specifically, to Qazvin, which is geographically located 180 km northwest of Tehran. There are several fine buildings in Qazvin because it was the capital of the Safavid Empire between 1548 and 1598. (I’ll tell you who the Safavids were when we get to Isfahan. You’ve learned enough about history for the day!)

Reconstruction works at the Jameh Mosque of Qazvin. Photo: KW.

Among the buildings is the Jameh Mosque of Qazvin, a Seljukian-Safavid construction, which was allegedly already founded by Harun al-Rashid. That, however, doesn’t show anymore today. The only thing you do see today, actually, is a courtyard and one where not much was going on.

Imamzadeh Hossein. Photo: KW.

By no stretch of the imagination can you say that about the Imamzadeh Hossein, which is a very busy pilgrimage site. A two-year-old boy is buried here: not because he did something special but because he was the son of one of the twelfth imams recognised by the Shiites.

The tomb of Hossein. Photo: KW.

Little Hossein died when his daddy stopped in Qazvin on his travels in 821. Now he lies buried in a magnificent sarcophagus and serves the same purpose as the pictures of Virgin Mary in our pilgrimage churches.

Hard-core Muslims, by the way, are not at all happy about such superstitious practices. Like Calvin did once, they rail at the stupid women folk, who believe themselves in need of such intercessors. That doesn’t bother Hossein’s fans at all. The grave mosque is their refuge and sometimes also a place to rest or do your homework.

Putting on the hijab. Photo: KW.

Anyway. First thing on arrival, hijabs were being put on us so we wouldn’t dishonour the sanctity of the place. But not the elegant, black coats that we had admired on many slim Iranian women. Ours were made of synthetic material, way too hot, of a dirty brown colour and anything but fashionable. Besides, putting this thing on is not that easy at all. When I took a little longer to slip into it, an Iranian woman took my arms and energetically shoved them into the sleeves.

A glance into the sanctuary. Photo: KW.

Dressed like that we were allowed to enter our part of the sanctuary. In there we were bestowed with curious looks and cordial greetings. Nobody felt disturbed by our presence, on the contrary. We provided an exciting topic of conversation. “Where do you come from? Welcome to Iran!” As you can see, taking pictures was also permitted.

An automated dispenser for prayer candles in the sanctuary, something other religions do too. Photo: KW.

After that it was lunch time. The way to the restaurant was pretty long, pretty hot and along a pretty busy street, not quite the touristic highlight. Our local guide Ehsan took the lead while staring at his phone in concentration, on which Google Maps was showing him the way. He couldn’t admit that he had no clue where we were going after all. Only very few tourists ever come to the north. At least we found the restaurant eventually, ate a fantastic meal, even if it was a bit too heavy on the chicken and mutton again. With a full belly I fell asleep on the bus and missed most of the 150 and something km to Soltaniyeh.

Ilkhanate. Öljaitü, 1304-1315. Dirhem, Amul. From CNG auction sale 369 (2016), 606.

Let’s admit it: Soltaniyeh is a dullsville. A really small one, to be precise. It is more reminiscent of the end of the world than of a capital. And still it used to be a booming centre when towns in Germany only began to take shape.

A Mongolian prince studying the Q’ran. Source: Wikipedia.

Öljaitü was an Ilkhanate. That means he ruled over a part of the Mongolian empire. His predecessors had been direct subordinates to the successors of Genghis Khan. At the beginning of the 14th century, however, when Öljaitü came into power, the central government had lost control over his Khanate so that Öljaitü could do as he pleased.

This Öljaitü (I simply like the name, I cannot write it often enough and maybe, someday, I’ll even remember it!) had gotten about a lot when it came to religion: originally baptised as a Christian, he had converted to Buddhism as a young adult, then confessed to Sunni Islam a little bit only to convert to Shia Islam later.

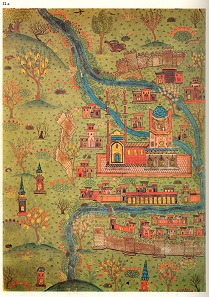

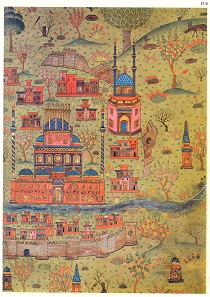

Map of Soltanyieh from the 16th c. Source: Wikipedia.

Öljaitü founded Soltanyieh in 1306 and planned to make it a religious centre. To this end he wanted to bring the remains of the highest Shiite martyrs, Ali and Hossein, to Soltaniyeh. He also had a large sanctuary built in advance. Unfortunately neither Najaf nor Karbala could do without their profitable dead.

Öljaitü’s magnificent tomb. Photo: KW.

Tough luck. Now there was the structural work of a magnificent tomb and no martyr in sight. Öljaitü made the best of the situation. Without further ado, he rebranded the construction and had himself buried in it.

A look inside the tomb of Öljaitü. Photo: KW.

It is hard to find words to describe the sight that was offered to us adequately. Maybe it is enough to say that it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. And while, in other regions of the world, tourists knock each other over to see cultural heritage sites elevated to the UNESCO ranks, we were all alone. Our group and no one else.

The tomb of Öljaitü is embellished with the most delicate ornaments on the inside. Photo: KW.

The sanctuary is as impressive on the outside as it is elegant on the inside.

Decorated dome on the first floor. Photo: KW.

Narrow stairs lead to the first floor, where visitors can follow a circuit through numerous rooms with beautifully decorated domes.

The outer circuit on the second floor. Photo: KW.

There is another round tour on the second floor. What is missing, on the other hand, are properly secured banisters, toilets, postcards and, not to mention, a café. As I said, tourism in this country is still in its infancy.

Look at the dome. Photo: KW.

We were not able to get a look into the dome as Iran’s oldest double-shelled dome is currently undergoing restoration. At least the outer shell is completed now. We were still impressed, though, that the master-builder here had the idea to build a double-shelled dome a century before Brunelleschi, who built the dome of the Florence Cathedral in 1436.

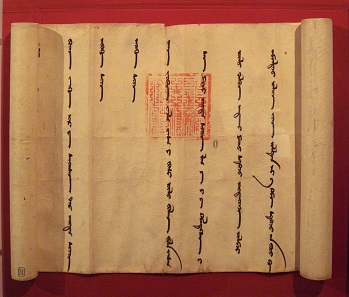

Letter from Öljaitü to Philip the Fair from 1305. Source: Wikipedia.

Perhaps I should have approached the matter from a different perspective: Why could Brunelleschi not have gotten his inspiration from Soltanyieh? Even with leaving Marco Polo out of the picture, there was an animate dialogue going on between East and West, i.e. between Genoese and Venetian tradesmen and Soltanyieh. We even know that Öljaitü was attempting to form a coalition with Philip the Fair and the Pope. In 1305, 1307 and 1313, he sent delegations to the West to find allies against the Mamelukes.

Be that as it may. Our journey continued. We had a little under two hours left to Zanjan, where we would spend the night. Oh had we only known how good the hotel was where we rested this one night. We would have appreciated the few hours of sleep even more!

In the third part of my Iran travelogue, you learn what the average study trip traveller must suffer. We visit the Throne of Solomon with its fire temple from Sassanid times and learn more about Zoroaster. And, last but not least, I will tell you why every Iranian hotel – no matter if it has 2 or 5 stars – has a pair of plastic shoes with high wedges in its closets.