by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

February 23, 2017 – Do you know what Newroz is? No? Well, you can’t travel Iran on March 20 or 21 without experiencing Newroz. It is the Iranian New Year and the celebration of the vernal equinox, and the most important family holiday in Iran. Everybody celebrates Newroz, orthodox Shiites, Zoroastrians, the few Christians that there are, simply everyone. It’s a little bit like Christmas and Easter together. The Christmas part is that something is being decorated – not a tree, in this case, but a table, and the Easter part is that the whole family goes for a walk together. And this amazing holiday we spent in one of the world’s most beautiful cities, in Isfahan, of which the old poets say that Isfahan alone offers half the world.

The most beautiful breakfast room I’ve ever seen in my life. Even the chairs were modelled on the royal Achaemenid throne. Photo: KW.

Saturday, 19 March 2016

Today I had breakfast in the most beautiful breakfast room I’ve seen in my life so far! And I could take all the time I wanted. Yesterday we had checked out with Ms Hodel because we thought we could handle Isfahan on our own. So we’ll explore the city by ourselves and take as long as we want.

Not pressed for time we sat there, watching the Iranians come to have their breakfast. The foreigners or, in other words, the tourists, had already left. After all, they had a full schedule to get through.

We didn’t. Instead of the Jame Mosque, we saw an adorable petite Iranian woman with a blue headscarfhop over to the buffet again and again to fill her family’s plates with everything that was desired or had been forgotten the last time. At a different table, a young mother relied on a trick to feed her reluctant baby girl: Daddy had to hold his eyes shut and whenever he did that, mother and daughter surprised him by having yet another bite vanish from the plate. Across the room, three generations of a family sat together: Granddad and grandchildren did not come to an agreement. That much was clear from their gestures, although I have no idea what the disagreement was about.

Naqsh-e Jahan Square in the centre of Isfahan. Photo: KW.

So we only left the hotel at 9.30 am! What sin! And that in Isfahan of all places, where there is so much to see! And see much we did. We saw half the world.

Gamasp, 496-498. Obol year 1 (496/7), minted in Isfahan (mint mark AS). From Peus sale 380 (2004), No. 641.

Already the Greeks knew Isfahan. They called it Aspadana. At least it is listed under this name in the geography of the Alexandrine scholar Ptolemy (c. AD 100-160 AD). Of course Isfahan is much older. Excavations have discovered traces of settlements which go back until the Old Stone Age. But Isfahan only achieved real significance under the Sassanids, who made their army camp here and established a mint in the city.

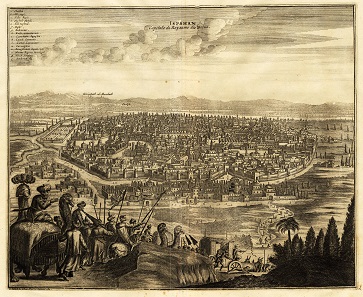

The city of Isfahan, capital of the Persian kingdom. Engraving from 1725 by P. van der Aa.

That Noah Gordan sends the hero of his novel “The Physician” as a Jew to Isfahan of all places has a historical precedent. Isfahan was famous for its large Jewish community. Even if the Bible wants to link it to Cyrus, it only came into being under Sassanid rule. The Jewish spouse of Yazdegerd I founded a colony for her fellow believers here. In the centuries to come, new and old settlement merged into one.

Faramarz, 1041-1051, as vassal of the Seljuk Thugril. Dinar 1043, Isfahan. From Gorny & Mosch sale 120 (2002), No. 4409.

In the course of the 10th century, Isfahan became a wealthy trading city ruled by very different dynasties until the Seljuk Thugril made it its capital in 1051 and heralded its most prosperous era. The Physician is set precisely in this time (and pays no regard to such boring details as the historically correct dynasty in power. I mean, why would it? Those Islamic rulers are all the same anyway… And what could possibly be wrong with a name like Allah Shah?)

Mongols. Ilkhanates. Abaqa, 1265-1282. Dinar, Isfahan. From CNG sale 281 (2012), 539.

After the Mongols had assumed power, Isafahan’s importance declines – first slowly, then quite rapidly, when Temür ibn Taraghai Barias, better known as Timur or Tamerlane, took the city in 1228, slaughtered its inhabitants, and had their heads piled up into towers as high as minarets.

The battle between Shah Ismail and Khan Shaybani. Fresco in the Forty Columns Palace. Photo: KW.

Shah Ismail (1484-1524) is considered the founder of the Safavid Empire, but Abbas I of Persia, also Abbas the Great (1587-1629), was more important for Isfahan. He consolidated the empire, extensively expanded its borders, and made Isfahan his capital.

The conquest of Tabriz painted by a European traveller. The heads of Ottoman Turks are spiked on poles, a welcome sight in Europe at the time.

The Shah of Persia became the talk of the town everywhere in Europe. After all, he was the other great enemy of the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg dynasty would have loved to win him as an ally. That no new Turkish attack on Vienna was attempted during the Thirty Years’ War is probably largely due to the fact that the Ottoman Sultan was fighting the Persians.

Safavids. Abbas, 1578-1629. Mithqal, Isfahan. From Peus sale 400 (2010), No. 779.

Under Safavid rule Isfahan became one of the grandest cities of the world at the time. Round about 600,000 people lived there – Zurich, by comparison, had only some 5,000 inhabitants at the time. And all the magnificent buildings! Back then Isfahan presumably had some 150 mosques, 50 madrasas, and 200 bath houses.

The Procuress, oil on canvas, 1656 by Johannes Vermeer, depicting a precious rug.

Isfahan was the most important trading centre between West and East. It was here that the great trading companies from England, France, and the Netherlands established holdings. Here they bought the precious silk which travelled to Europe from China via Isfahan. Persian rugs were so highly coveted that in German the word “Perser” (“Persian”, short for “Persian carpet”) has even come to be a stand-in for woven carpets in general.

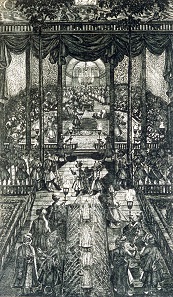

Engelbert Kaempfer is being received at the Persian court. Contemporary steel engraving.

The young German researcher and traveller Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) also came to Isfahan on his travels and described it in much detail. Among others, he mentioned that it took two days to circle the city walls on horseback.

The Shah of Persia receives the Indian Mughal ruler Humayun. Forty Columns Palace. Photo: KW.

The end of the Safavids came in 1722, when Afghan troops mutinied, laid siege to the city, and forced the last Safavid to abdicate. Therewith Isfahan lost its status as capital, which was perhaps to the best. As it is, many buildings which might have been replaced in the 19th or 20th century by larger ones could be preserved.

Maidan, or Naqsh-e Jahan Square. Photo: KW.

But back to our city tour. We were standing in Naqsh-e Jahan Square, the central square in Isfahan. It is huge. I don’t know any one square or courtyard from pre-Modern times that is even remotely as big. The centre is occupied by a shallow water basin, complete with water gushing from the fountains to honour the New Year. Surrounding the basin are elegant galleries, which offer everything to the tourist heart’s desire.

Galleries on the ground level floor; then, as now, the scene is perfect for a stroll. Photo: KW.

Already Kaempfer was enamoured with this square: “The square is shaped like a rectangle, 660 feet long and 212 feet wide. All around it are two-storeyed, vaulted niche buildings. The upper rooms are separated into small chambers, which are rented out as bedrooms to all sorts of strangers and also to harlots. The ground level floor serves partly as a promenade, but mostly it houses spacious bazaar stalls for craftsmen and hucksters, who manufacture and offer all kinds of goods for sale there. Still, disorder does not rule here but everyone is assigned a place according to his profession.”

Look at the Safavid palace. Photo: KW.

Situated on two sides of the square are two mosques, the palace of the Safavids is on the third side, and the entrance to the bazaar on the fourth (although we realized that only after kilometre-long detours…).

First we visited the palace, but unfortunately found it somewhat disappointing. And that despite Kaempfer’s raving accounts of it: “Although it is not in accordance with the classical style, I do find it quite charming. In the centre of the terrace is a rectangular marble basin with a water fountain. Also the rest of the furniture is of the most exquisite Persian taste.” Anyhow. At least the view from the terrace was phenomenal.

The bazaar of Isfahan – not just for tourists after all… Photo: KW.

Then we wanted to see the bazaar. That was easier said than done because we had decided to leave the heavy art-historical travel guide in our hotel room and use the city map of the hotel instead. Well, the graphic design was prettier, it had a few useful numbers on it, and was way too smart to be read by anyone not from Isfahan.

So we had to rely on our memory – yup, we had taken a look at the travel guide at the hotel – as well as on the city maps in Farsi and English put up by the municipal administration, and ended up on an interesting walkabout with many insights into Isfahan’s everyday life. A good hour later we even discovered a bazaar. Unfortunately not the one we were looking for. All sorts of cars, delivery vans, motor bikes, and pushcarts were driving around there and it smelled like a garage.

A bazaar for the locals. Photo: KW.

We kept walking straight ahead, kilometre after kilometre. We saw stalls with hair clips and underpants, curtains and pans, t-shirts and Chinese headscarves. No trace of the craftwork Isfahan is so famous for. Finally we discovered a water fountain which signified that we’d found the older part of the bazaar. We saw little stalls with gold jewellery and now our stroll could have really begun, if our feet hadn’t been hurting so much.

The impossible becomes possible: this café serves good coffee after the European fashion. It is easy to find if you don’t take endless detours. It is right next to the entrance to the great bazaar. Photo: KW.

And then the impossible, the long hoped-for, that which we had not believed to be possible anymore, happened. In front of us a sign with the label “Segafredo” popped up. Of course we sat down at the only free table left. We ordered a double espresso. “Doppio” repeated the waiter laconically. A good sign! To cut a long story short: The espresso served there was indeed Italian. The first we’d gotten anywhere in Iran. And despite its prices, which were very high by Iranian standards, the café was crowded. We were lucky to get the two chairs.

So refreshed we gathered courage to find the bazaar’s exit. We walked towards the light with the vague hope that we would be able to orient ourselves from there. We were. The exit led into the open, to the Maidan. What we’d done was quite an accomplishment, actually: Coming from the square, we had found the back entrance to the bazaar and wandered about until we reached the main entrance. There would have been an easier way to do this. But it wouldn’t have been the same…

The private mosque of the Shah of Persia. Photo: KW.

One mosque. Nor more than that. We had sworn we wouldn’t see more today. Our chosen mosque was the private mosque of the ruler. It is located – how could it be otherwise – next to the square and it is said to be the most beautiful mosque in the world.

A look at the interior of the dome. Photo: KW.

Of course I don’t know all the mosques of the world, but this intimate building surely deserves a place in the top ten. I have rarely seen such a balanced, well-proportioned, and friendly space. The many shades of blue are brightened up by a warm, earthy colour. And that, as we learned from Ms Hodel, is a sign of it being a private mosque.

The mihrab, without children romping about, without couples taking selfies, extended families taking selfies, or idiots so busily talking on the phone that they don’t realize they’re in the picture. Photo: KW.

The locals enjoy their mosque at least as much as we arty tourists did. The place was packed. And it was close to a miracle that I got a picture of the mihrab without an Iranian woman with a baby on her arm. It seems like mihrabs are the perfect selfie background. (Whereas the concept of taking pictures solely of the architecture, without any people in it, is not met with understanding.)

We strolled around the square some more, looked into shops, and observed how Iranian families spend their holiday. Then we had enough and were back at the hotel by 3.00 pm. Have you ever heard of such a thing! So many great mosques are in the surrounding area, and probably will still be there in 100 years even if I don’t go to see them…

Instead, we sat in the hotel’s traditional tea house sipping delicious tea, writing diary, and enjoying the day. Sometimes I think travelling shouldn’t be merely ticking sights off the list but also just being and enjoying the moment.

In the lobby, hotel guests waiting for Newroz to begin. Photo: KW.

Newroz, Sunday, 20 March 2017

To be honest, we didn’t quite know what was going on in the lobby when we headed to breakfast in the morning. Dozens of families were standing around, waiting, watching the table set up for Newroz, and then again waiting some more.

The table set up on Newroz. Photo: KW.

Somehow the Newroz tables remind me of our Christmas decorations. It looks a little different in every house but basically it’s always made up of the same elements. The same goes for the Newroz table. Here the theme is the seven “s”, seven things which begin with an s and which can vary from one table to the next. Sabzeh (= cereal), samanu (= a sweet dish),…

Garlic as Newroz decoration. Perhaps an inspiration for the next Christmas tree, maybe instead of the traditional Christmas tree ball? Photo: KW.

… sir (= garlic), …

The “Persian olive”, the fruit of the elaeagnus angustifolia plant; I have not the faintest idea what it tastes like but I am told it tastes good. Photo: KW.

… senjed (= Persian olive), serkeh (= vinegar, which used to be wine before the Islamization), somagh (= elm-leaved sumac, a spice), …

Apples on the festive Newroz table. Photo: KW.

… and sib (= apple).

Coins, indispensable on Newroz. Photo: KW.

Another item on the table is sekeh (= coins), which symbolises wealth. Apparently the national bank specifically releases freshly minted coins and brand new banknotes for circulation before Newroz.

And, of course, the goldfish! Photo: KW.

Already weeks in advance, the small goldfish, which symbolise fortune on the Newroz table, are sold out on all bazaars across the country. What happens to them afterwards? Well, that remains a secret (and one that I honestly don’t want to know).

Not everybody is happy on Newroz. Photo: KW.

Anyway, we just joined the waiting crowd. Not on the ground floor, but on the gallery above, from which we had a good view. Then somebody said something – as I have learned in the meantime, he announced the beginning of Newroz. And then all hell broke loose. Everybody hugged everybody else. And wished them luck. And gave away presents. And laughed. And beamed. And then I raised my eyes from the cheerful crowd below and saw the people on the gallery with us. The maids on the left, the boys on the right. They didn’t laugh but looked down in a very serious manner. One woman turned away because she was crying and didn’t want to be seen like this. Another man was crying too and affectionately surrounded by the other boys. I suppose they felt like people who cannot spend Christmas with their beloved ones because they have to work at a distant place. Over the holidays the imposed distance from the own family must hurt more than usual.

Newroz table afloat on the water. Photo: KW.

Of course all tourist attractions were closed on Newroz. Thank God. We wouldn’t have had time anyway since we much preferred going with the flow and joining the others in their celebration. The city was packed; families from the surrounding areas had come to town together. I think on our walk I received enough invitations to feed me until the next Newroz celebration. The Iranians, which are very sociable anyway, are even more so on Newroz.

Let’s stop the account of this journey across Iran here, with this outlook on Newroz. The only thing left was our journey home. We had to get up at 1.45. Not pm. am. And the shift to summertime gave us the rest. When the alarm went off at 1.45, Kurt’s watch said it was 0.45 and the hotel clock said 11.45 – utter confusion.

We went down to the lobby a little bit earlier to be safe because we hadn’t been able to pay our hotel bill the night before. After all, we could have taken another coke from the minibar, which was being checked by the hotel staff precisely at the moment when we were asking to pay our bill, couldn’t we?

We took off to Istanbul at 5.45 and arrived home in the early afternoon. Well, we did, but our luggage didn’t. My adventurous suitcase had taken a little detour via Erbil, Iraq. And I had already wondered why the Farsi-only speaking airport staff had put my suitcase on a different conveyor belt. Unfortunately, the vocal concerns I had raised in English only vanished into silence in the sleepy airport hall…

And thus ends my numismatic travelogue of Iran – and for all those, who still can’t get enough of my numismatic diaries: The next one, documenting my travels in the south of Spain, will follow in mid-April. But first, I have to go travel some more so I can write about it…

You can find all episodes of my Iranian travelogue here.