by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Christina Schlögl

June 14, 2018 – Poland witnessed three partitions until the country did not exist anymore. We all learned this in school. But only few people have considered what this meant for the museum identity of this nation. After all, when the country was divided, people naturally took the easily portable and precious coins and medals from the collection of the Polish king Stanislaw Augustus with them…

Facade of the gigantic National Museum in Warsaw in the year of 1938. Photo: Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN 1959.

The Polish National Museum

Even though most normal visitors will not notice it, the Polish National Museum – Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie – has the largest numismatic collection in Poland. But this is just a small part of the National Museum. Let us insert a few figures here: The museum was founded in 1862 and it got its status as Polish national museum in 1916. It has extensive collections containing – and this does not include the numismatic collection – more than 780,000 objects.

A glance into the Faras Gallery with Nubian and Early Christian art. Photo: UK.

Here you will find the biggest European collection of Nubian art and the biggest collection of Chinese art in Poland. (Although there are also some interesting Chinese numismatic objects in the coin collection…)

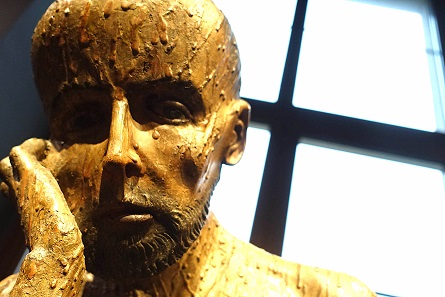

Man of Sorrows from 1502. Photo: UK.

Personally, I was deeply impressed by the gallery with religious art from the Middle Ages. The art work on display consists of absolute highlights. Visitors will appreciate that they are not flooded with mediocre art but instead they are presented with a selection of individual masterpieces.

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902), The Christian Dirce. Photo: UK.

If you love historicism, you should not miss the National Museum! You will find great paintings here! And if you feel like you are familiar with this motif, I should probably remind you that the Author of “Quo Vadis”, Henryk Sienkiewicz, was a Polish man.

This is practically an icon of Polish historicism, the painting of the Battle of Tannenberg (Grunwald) by Jan Matejko from the year 1878. Photo: UK.

This image by Jan Matejko, which depicts the Battle of Tannenberg (Grunwald), is practically iconic. It was painted in Krakow, which belonged to Austro-Hungary at the time and it pursued a relatively liberal policy in 1878. The painting – and the perspective on history it conveys – was received with great enthusiasm. The Krakow city council honoured Matejko as king of painters.

Let me take this opportunity to mention that the later Nobel Prize winner Sienkiewicz took this painting as inspiration for his very readable novel on Teutonic Knights. Readable not in a literary way but as a valuable historic source – to show how history can be used to convey political messages.

And with that we have arrived at the fact that the painting was hidden from the German Wehrmacht at the hazard of the concealers’ lifes and it was the same painting which hung behind Lech Kaczynski when he announced his candidacy for Polish state president. This painting is just much more than a painting. It is an important part of Polish identity.

Andrzej Romanowski in front of one of many of his big safes. Photo: UK.

But enough about historico-cultural detours. We are of course mostly interested in the coin collection. And it is a fascinating coin collection, as Andrzej Romanowski demonstrated in a guided tour which took almost two hours. And even then we had to limit ourselves to the absolute highlights.

Boleslaw I, called the Brave, first king of Poland since 1025. Denarius. – The effigy inspired the logo of the International Numismatic Congress. Photo: National Museum Warsaw.

The greatest numismatic collection of Poland

Let’s start with a few figures: The National Museum features the largest numismatic collection in Poland with roughly a quarter of a million objects. The spectrum ranges from antiquity to the present day, it has coins and bank notes but the collection of Polish coins is certainly the most extensive part – there are 58,000 inventory numbers.

This is all the more interesting because the collection, as we have already mentioned, does not go back to a royal collection. With the first Partition of Poland in the year 1772, the entire stock was transferred to Kiev. Why Kiev? Well, Kiev was once part of the kingdom Poland-Lithuania and it only belonged to Russia from 1667. Today, Kiev is in Ukraine. Consequently, the collection can be seen in the National Museum of the History of Ukraine.

The Treaty of Riga which ended the Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921), contains a clause which states that a selection of numismatic objects should be returned from Soviet possession to the national coin collection of Poland to make amends especially for the scavenging of the coin collection of the University of Warsaw. This promise was kept and these coins were the foundation of the new coin collection.

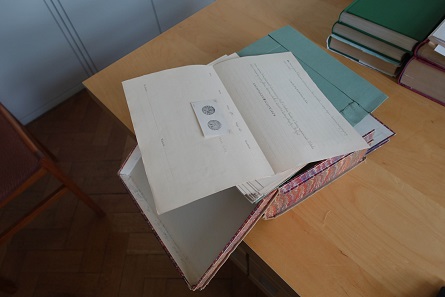

The collection of the count Sobanski was catalogued by Gumowski, a great expert of Polish numismatics. Andrzej Romanowski can still use this catalogue until this day. Photo: UK.

The Sobanski collection

It was in the same year that the museum got the collection of the count Kazimierz Sobanski, which was known to be one of the most precious collections of Poland during his lifetime. It is said to have consisted of almost 11,000 Polish coins and medals, which ranged from the time of King Sigismund the Old until 1867. Shortly before his death, Count Sobanski left his collection to the city of Warsaw. He settled a rent which was planned to be used to finance a curator. Due to administrative reasons, the collection has been on display at the National Museum not before the peace agreement with the Soviet Union.

Every coin has its own entry. Photo: UK.

Today, there are “only” 8,882 items of this collection at Warsaw. Count Sobanski had numerous gold coins which were plundered and smelted down during the time of German occupation.

A glance into the workspaces of the coin cabinet. Photo: UK.

The collection of the National Museum grew rapidly afterwards. In 1922, they bought the collection of early medieval coins of Baron Józef Weyssenhoff. In addition, all significant hoards of the country went to the museum.

The room with the safes. Photo: UK.

The German occupation brought great change. The museum lost 50% of its stock to plundering. And so things had to be rebuilt. The collection of the destroyed national mint was transferred to the National Museum. Some privately owned collections were confiscated by the new communist government and taken to the museum as well. One example for such a collection would be the Potocki collection, which had been brought together since the first half of the 19th century.

Magnentius. Solidus, Aquileia. Photo: National Museum Warsaw.

Naturally there are not only Polish coins at the National Museum. There are more than 40,000 coins from antiquity for instance. Wladyslaw Semerau-Siemianowski donated a basic stock of almost 30,000 coins from his estate in 1921.

China. Province Fengtian. Dollar, 1903. Photo: National Museum Warsaw.

And the 50,000 coins and medals from Europe, the ca. 4,000 Chinese coins, the 19,000 bank notes, more than 17,000 seals and their imprints as well as the extensive collection of orders and awards are certainly very impressive.

It is all the more disappointing that there is no permanent exhibition of numismatic objects in the generally accessible part of the National Museum. The coin gallery, which was installed in 2012, had to be closed again. It is thus great news that Alek Bursche has informed us that the gallery will be opened for the International Numismatic Congress. The contract for this exception has just been signed.

Canaletto, view from Warsaw overlooking the Royal Castle.

The Royal Castle, Warsaw

The Warsaw Castle Square is at a walking distance of only half an hour. The way from coin collection to coin collection is gorgeous and offers enough pretty cafes and interesting shops to take some time to relax.

The Castle Square is the entrance to the old town. It gets its name – surprise, surprise – from the Royal Castle Warsaw.

The Royal Castle during royal weather. Photo: sfu, cc-by3.0.

The castle was completely torn down by German soldiers on September 4, 1944. Today, the Castle stands in its place again.

A glance at the numismatic collection, which is only open by prior appointment. Photo: UK.

The numismatic collection

And this Royal Castle has a numismatic collection which can be viewed after advance reservation.

Michal Zawadzki and Grzegorz Sniezko in the permanent exhibition at the Royal Castle Warsaw. Photo: UK.

I had made an appointment with Michal Zawadzki and was greeted by him and his colleague Grzegorz Sniezko in the gallery.

The exhibition is split: There are coins on one side and medals, banknotes and orders on the other. Photo: UK.

Looking at the cabinets, one does not notice that the collection of the Royal Castle was only created in 1981. It has more than 15,000 Polish coins, bank notes and orders, which were donated, or bought with sponsored means on the free coin market. In the 1980s, the representatives of Castle collection were well-known and popular guests at the important European auction houses and some objects come from the great collections which were auctioned at the time.

It was as early as 1982 that the descendants of the Polish general Jerzego Wesierskiego living in Great Britain gifted his collection of 3,234 coins and medals to the castle museum. Other collections ensued and in 1985, a permanent exhibition of coins and medals from Poland was opened, which uses spectacular objects to tell the country’s monetary history.

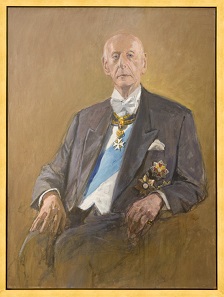

Portrait of Andrzej Chiechanowiecki.

A benefactor of the Royal Castle: Andrzej Ciechanowiecki

The collection of the Polish-British art historian Andrzej Ciechanowiecki, which is permanently accessible as a permanent loan at the cabinet is particularly remarkable. Do not miss out on reading his biography on Wikipedia. It describes a highly intelligent, brave man, who was part of the Polish resistance, who served Poland directly after the war as an ambassador, which lead to a long period of communist imprisonment later on. He wrote his doctoral dissertation in German at the University of Tübingen, while teaching Polish language and Polish culture at the university himself. He was a fellow of the Portuguese Gulbenkian foundation and decided to start a career as an art dealer in London in the 1960s.

This art dealer loved – like many other art dealers do – art and he loved his native country, therefore he used his respectable income to buy Polish antiquities which were sold for good value at the time. He hoped that he would be able to bring them back to Poland at some point. When the rebuilding of the Warsaw Castle was planned, he established a foundation, which provided 3,000 objects to decorate the Royal Castle. Among those objects were coins and medals, as well.

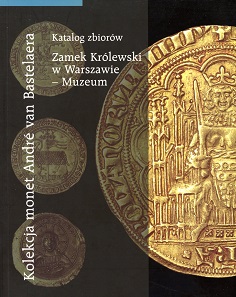

The publication of the André van Bastelaer collection.

And the acquisition policy continues. In 2016, the catalogue of the André van Bastelaer collection, which was recently donated to the Royal Castle Warsaw, was published. It entails 583 coins and medals, with an emphasis on Roman and Byzantine antiquity as well as Belgian coins.

Many of them are gold coins and a lot of them are unique! The most important specimens are supposed to be on display during the International Numismatic Congress and an English catalogue is planned to be printed.

A cabinet which was specially made for a daktyliothek, a collection of plaster casts of gems, which was very popular in the 18th and 19th century. Photo: UK.

The corresponding desk, with an antique vase at the right. Photo: UK.

A few numismatic glances during the round tour of the Royal Castle

Aside from the coin cabinet you should not forget to take a look at the rooms of the castle. It is definitely worth it, even from a numismatic perspective. The room where Stanislaw Augustus kept his coins for instance, is part of the tour.

A cup with portrait coins of the Polish kings. Photo: UK.

And the silver hall features some precious coin-vessels.

A Baroque bowl with gems. Photo: UK.

If you like gems, you will surely ponder over this Baroque set which is decorated with ancient and modern gems.

Approachable Polish history: The room with portraits from the Polish kings. Photo: UK.

I really liked this gigantic museum, where one can get footsore, especially because it is thus a museum for young folk.

A glance into old Warsaw. Canaletto’s paintings do not only shape our image of Warsaw, they have also shaped the actual city, since his paintings were used as models for the reconstruction. Photo: UK.

There is one highlight, no visitor should miss: the room with Canaletto’s 22 paintings of Warsaw. Luckily, they were preserved because German soldiers stole them from the castle. And it was due to these detailed paintings, that parts of the old town could be reconstructed after the Second World War.

In the next episode we will introduce you to the Polish Numismatic Society and we will take a detour to the Polin-Museum, the museum of the history of Polish Jews.

You will find the first part of our report on Warsaw here.

The website of the Polish National Museum can be found here.

If you can read Polish (or know how to use Google Translate) you can find extensive information on the numismatic collection of the National Museum with great pictures here.

Here you’ll find a few highlights of the Polish coinage.

And here you can take a glance at the ancient coins.

If you love sigillography, you will love this link.

If you are interested in the highlights of the National Museum, here is a Youtube podcast by Radio Poland.

This trailer of Quo vadis will show you how Hollywood has adapted the “Christian Dirce”.

This is the English website of the royal castle.

Incidentally, the Lanckoronski collection there does not go back to the relatively famous Swiss numismatist Leo Lanckoronski but instead to his lesser known father Karl.

Here is some information on the coin collection in the Warsaw Royal Castle in Polish language…

… and on the collector Kazimierz Sobanski.

You can order the catalogue of the André van Bastelera collection for 99,00 zloty plus shipping here. The catalogue will be available in English in 2021 for those who can wait that long!

There is a beautiful film on Canaletto presented by the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

Even today, every state visit will have a greeting in the Royal Castle Warsaw. Donald Trump visited the castle in 2017.

Much fewer people have seen this impressive film fragment on the fire in the Royal Castle.

And here you’ll find a podcast on the rebuilding.