The State Department Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and US Customs and Border Protection have imposed extremely broad “emergency import restrictions” on cultural goods “sourced” to Afghanistan. The restrictions that were put in place address few of the concerns raised by representatives of museums, collectors and the small and micro businesses of the numismatic and ethnographic art trades at a rushed Cultural Property Advisory Committee meeting that took place on 5th October 2021.

“The Designated List includes archaeological and ethnological material sourced from Afghanistan. Archaeological material ranges in date from the Paleolithic (50,000 B.C.) through the beginning of the Durrani Dynasty (A.D. 1747). Ethnological material includes architectural objects and wooden objects associated with Afghanistan’s diverse history, from the 9th century A.D. through A.D. 1920.”

The real question is how these restrictions are going to be enforced and if any material that may be seized will be repatriated to the Taliban once diplomatic relations are restored. CPO also wonders if these “emergency import restrictions” will morph into a memorandum of understanding with Afghanistan’s Taliban government as was recently done with Libya.

There also is a significant issue whether these import restrictions were promulgated legally. As recounted in the Federal Register Notice, a request from the former government of Afghanistan was only acted upon after that government fell. Although Afghanistan’s former government evidently requested a MOU, “emergency import restrictions” which do not require a signed agreement were imposed instead. Such “emergency import restrictions” also require a “request” from a “State Party.” See 19 USC § 2603 (c) (1). Thus, the same question arises, can the State Department act based on a “request” of a government that no longer exists?

There also is a significant practical issue for collectors, museums, the trade as well as the representatives of displaced religious and ethnic minorities. “Emergency restrictions” were contemplated to be imposed on a much narrower range of cultural goods than “regular restrictions.” The baseline requirements of “cultural significance” and “first discovery” still apply, but emergency restrictions otherwise focus on material of particular importance. In essence, the material must be a “newly discovered type” or from a site of “high cultural significance” that is in danger of “crisis proportions.” 19 USC § 2603 (a). Alternatively, the object must be part of the remains of a civilization, the record of which is in jeopardy of “crisis proportions,” and restrictions will reduce the danger of pillage. Here, in contrast, the “emergency import restrictions” that were imposed are hardly narrow. Rather, they are instead exceptionally broad, including items produced as late as the 1920’s.

The one bright spot is that the designated list does not include “textiles” under the ethnographic category. If it did, such import restrictions would potentially devastate the livelihoods of Afghan women who make a living weaving textiles for export.

Aside from that, the exceptionally broad designated list is concerning because import restrictions are not applied prospectively solely to illegal exports made after the effective date of regulations under 19 U.S.C. § 2606, but rather are enforced far more broadly against any import into the U.S. made after the effective date of regulations, i.e., an embargo, not targeted, prospective import restrictions. It remains to be seen whether the Federal Register’s limitation to cultural goods “sourced” to Afghanistan has any effect whatsoever on enforcement.

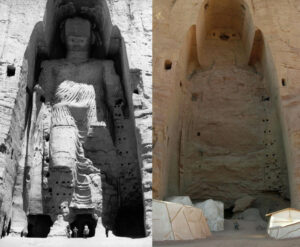

Those of the Buddhist faith should be particularly concerned about restrictions encompassing Buddhist material of the sort the Taliban has destroyed in the past. The inclusion of musical instruments under ethnological material is particularly chilling given the Taliban’s strictures against music and murder of a prominent folk musician.

The designated list of coins is particularly broad and includes coins that circulated regionally as well as internationally. It goes far beyond coins that “primarily circulated” within Afghanistan, the State Department’s prior standard and encompasses coin types (like Roman Imperial coins) purposely left of prior lists. Hopefully, such broad restrictions made on an “emergency basis” will not be cited as “precedent” in the future, particularly given the Federal Register’s requirement that they be “sourced” to Afghanistan.

Included Coins

Ancient coins include gold, silver, copper, and bronze coins; may be hand stamped with units ranging from tetradrachms to dinars; includes gold bun ingots and silver ingots, which may be plain and/or inscribed. Some of the most well-known types are described below:

- The earliest coins in Afghanistan are Greek silver coins, including tetradrachms and drachmae. Approximate date: 530-333 B.C.

- During the reign of Darius I, gold staters and silver sigloi were produced in Bactria and Gandhara. Approximate date: 586-550 B.C.

- Achaemenid coins include round punch-marked coins with one or two punched holes and bent bar coins (shatamana). Approximate date: 5th century B.C.

- Gandhara coins include janapadas, bent bar coins based on the silver sigloi weight. Approximate date: 4th century B.C.

- Mauryan coins include silver karshapanas with five punches, six arm designs, and/or sun symbols. Weights ranged from 5.5 to 7.2 gm. Approximate date: 322-185 B.C.

- Gold staters and silver tetradrachms were produced locally after Alexander the Great conquered the region. Approximate date: 327-323 B.C.

- Greco-Bactrian coins include gold staters, silver tetradrachms, silver and bronze drachms, and a small number of punch-marked coins. The bust of the king with his name written in Greek and Prakit were on the obverse, and Greek deities and images of Buddha were on the reverse. Approximate date: 250-125 B.C.

- Common Roman Imperial coins found in archaeological contexts in Afghanistan were struck in silver and Start Printed Page 9443 bronze. Approximate date: 1st century B.C.-4th century A.D.

- Kushan Dynasty coins include silver tetradrachms, copper coin (Augustus type), bronze diadrachms and gold dinars. Imagery includes portrait busts of each king with his emblem (tamgha) on both sides. Classical Greek and Zoroastrian deities and images of the Buddha are depicted on the reverse. Approximate date: A.D. 19-230.

- Sassanian coins include silver drachms, silver half drachms, obols (dang), copper drahms and gold dinars, and gold coins of Shapur II (A.D. 309-379). Starting with Peroz I, mint indication was included on the coins. Sassanian coins may include imagery of Zoroastrian Fire Temples. Approximate date: A.D. 224-651.

- Hephthalite coins include silver drachms, silver dinars, and small copper and bronze coins. The designs were the same as Sassanian, but they did not put the rulers’ names on the coins. Hephthalite coins may include imagery of Zoroastrian Fire Temples. Approximate date: 5th-8th centuries A.D.

- Turk Shahis coins include silver and copper drachma with portraits of the rulers wearing a distinctive triple crescent crown. The emblems of these Buddhist Turks were also included on the coin. Inscriptions were in Bactrian. Approximate date: A.D. 665-850.

- Shahiya or Shahis of Kabul coins include silver, bronze, and copper drachma with inscriptions of military and chief commanders. Hindu imagery is included on the coin design. The two main types of images are the bull and horseman and the elephant and lion. Approximate date: A.D. 565-879.

- Chinese coins belonging primarily to the Tang Dynasty are found in archaeological contexts in Afghanistan. Approximate date: A.D. 618-907.

- Ghaznavid coins include gold dinars with bilingual inscriptions, Islamic titles in Arabic and Sharda and images of Shiva, Nandi, and Samta Deva. Approximate date: A.D. 977-1186.

- Ghurid coins include silver and gold tangas with inscriptions and abstract goddess iconography. Approximate date: A.D. 879-1215.

- Timurid coins include silver and copper tangas and copper dinars, both coin types are decorated with Arabic inscriptions. Approximate date: A.D. 1370 -1507.

- Mughal coins include shahrukhi, gold mithqal, gold mohur, silver rupee, copper dams, and copper falus. The iconography varies, depending on the ruler, but popular designs include images of the Hindu deities Sita and Ram, portrait busts of the rulers, and the twelve zodiac signs. Approximate date: A.D. 1526-1857.

Peter Tompa is Executive Director of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild.

This post is based on a post from the cultural property observer blogspot.

You can find out more about Peter K. Tompa in our Who’s Who.

This is a link to the Federal Register Notice announcing the restrictions.

For a long time there was a myth that ISIS made millions of dollars in the antiquities trade. An expert from the British Museum declined that myth.

Here you can read about how to prevent trafficking in Afghanistans cultural heritage.