This article is a republication of: St John Simpson Interview: Afghanistan repatriation, Daesh, remote-archaeology and the ILLICID report

The British Museum’s Senior Curator for the Middle East talks about collaboration with foreign museums, restoring stolen art, and the museum’s role as expert witness to looting by Kate Fitz Gibbon.

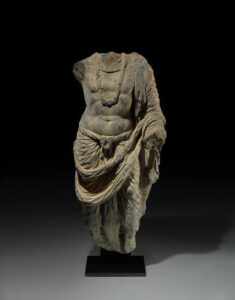

Dr St John Simpson is an archaeologist and the Senior Curator in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum, where his area of oversight also includes Afghanistan, Iran, and Central Asia. He has excavated extensively in the Middle East and Central Asia and from 1992-2000 co-directed an international collaborative project at the important ancient city-site of Merv in present-day Turkmenistan. His research delves deep into Sasanian and early Islamic-Late Antique and early medieval material culture from Iraq, Iran, the Persian Gulf and Central Asia, as well as ancient South Arabia. Some of his best-known exhibitions at the British Museum are “Queen of Sheba: Treasures from ancient Yemen” (2002), “Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World” (2011) and the most recent “Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia” (2017/18).

St John Simpson has been a key player in the successful collaboration between the National Museum of Afghanistan, the British Museum, the UK Border Force, the British Metropolitan Police Service (Art and Antiques Unit) and others in the return of stolen antiquities to Afghanistan.

When Britain implemented the Dealing in Cultural Objects (Offences) Act 2003, it became unlawful to import objects known to have been illegally excavated in or exported from another country. The law also covers objects that have not been stolen, but have been illegally excavated or removed from a monument. UK law enforcement asks the assistance of experts to determine the authenticity and origin of seized objects.

Kate Fitz Gibbon: Cultural Property News has published a number of articles setting out how Western institutions are rethinking their relationships with source countries and moving towards collaboration with museums worldwide. British Museum Director Hartwig Fischer addressed how these responsibilities are balanced with the museum’s obligations to preserve and study their collections in “Collections entail responsibilities: Notes on a global institution.”

Day-to-day, in your curatorial work, you are also dealing with war and the complete disruption of ordinary life in almost every region you cover. I wanted to talk about specific aspects of your collaborative work with institutions in Afghanistan and in Iraq and other Middle Eastern countries, on how these partnerships have evolved to meet the needs and capacities of the museums there, and of course about your work to repatriate looted objects to Afghanistan.

You have a truly unique position, working to connect all the parties involved in the circulation of art – where you can see the whole picture. You stepped forward recently to point out that cultural policies in Germany in particular were being driven by misrepresentations about the illicit circulation of art. Can we talk about that first, and get the unreal picture out of the way, and then talk about the realities, and the way forward?

St John Simpson: Yes, let’s get the ILLICID report out of the way.

The key fact about the ILLICID report is that out of the sample of the 356,500 objects that they say they looked at, only 0.1% were identified by them as genuine pieces from Syria or Iraq. That is very telling. I think it implies that there is a considerable amount of hyperbole about the volume of trafficking from those countries at least, even though there has sadly been a lot of destruction across the country. That hyperbole is something that we’ve seen in a lot of press stories over the last few years. Compare that to the fact that in the last nine years, we’ve not seen a single antiquity entering Britain or passing through Britain from Daesh-controlled areas of either Syria or Iraq. That’s despite the fact that the UK is a major transport hub and there has been very high-risk profiling of individuals and freight from Daesh-controlled areas. We have also yet to see any objects on the market which we can show might have been stolen from the Mosul Museum in 2015.

I think that the absence of any such objects that we can demonstrably prove comes from these past nine years of conflict is very telling. It’s in complete contrast to the decade-long period from 1993-94 to 2003-2004 in Iraq where the satellite imagery of the ground matched the market picture. At that time there was organized looting of sites known to produce cuneiform tablets, glass, seals, coins, bullae and those sorts of things and we had huge quantities of those things on the market. That’s also a period when there was looting at museums and museum pieces were identified on the market. So in Iraq, in that decade, there was a complete match between the different data sets, whereas in Syria and northern Iraq in the last 8 years there’s a complete mismatch. That is something that needs to be better analyzed and explained. And I think that’s where future scrutiny ought to lie.

What does it mean that you haven’t seen recently stolen pieces from the Mosul Museum on the market anywhere?

St John Simpson: I am not aware of them showing up anywhere internationally although pieces stolen before have. I’m afraid that the conclusion is potentially quite grim. That is that the Daesh propaganda, whether spoken, written or visual, emphasizes, as propaganda did in 2001 in Afghanistan, the destruction and defacement of imagery, which was seen to be a powerful counter message to their own ideology. What we’re seeing is a very parallel scenario. The Daesh were in fact destroying; they were not digging for the market. If they were digging for the market or trading, then we would have seen those Palmyrene busts that got intercepted by Daesh at a checkpoint near Jerablus being moved across the border into Turkey. Instead they took them off the lorry and smashed them in front of a crowd of people that they whipped up and for the cameras to observe.

The same goes for the secret storeroom in Palmyra. We know that the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums, just hours before Daesh took Tadmor, had whisked away large quantities of their stored antiquities. They relied on the fact that there was a hidden storeroom which no one really knew about to keep the remainder. Sadly, as we now know, the location of that storeroom was discovered by Daesh. They entered the facility, they beheaded all the sculptures and then walked away. Took none. They could have ghosted them all out of the country but they made no effort to. So I think this idea of Daesh in particular making millions of dollars out of traded antiquities is a complete myth. Or at least needs to be seriously supported by facts.

This is very important information coming from someone in your position.

St John Simpson: We have to look at and follow the evidence. That is what law enforcement does, and so do curators. In museums we are in an exceptional position because we know objects. That’s our bread-and-butter. We have to look at the market. We have to see what’s passing through it, genuine or not.

The British Museum is the key source of expert witness for all areas of UK law enforcement where objects are thought to have been stolen or trafficked, so we see it all. We see the export licences as well. This also applies to other national museums in other countries. So museums have an incredibly powerful role to play and to be a voice for the community as to what is really going on.

Museum professionals now work constantly with colleagues around the world, and this builds a cumulative historical understanding of how things work – wherever museum people are, they share this collective art historical memory of centuries. It seems that as a family, museum people share special traits and understandings as well as common goals.

St John Simpson: The idea that museum people belong to one family is a powerful one, which is not really widely understood outside the museum sector. There are several aspects to that which are of great importance. One of the great lessons of the conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, as in Britain and Russia in the Second World War, is that you’ve got to have a disaster plan. You should prioritize the high-value; move or hide objects as far as you can and share information on a need-to-know basis.

The curators, or keyholders as we call them from Afghanistan, who have been doing that are the heroes and heroines of cultural history for the past hundred years. When museum directors in those countries assure us that they can look after the objects that we’re looking to repatriate, we’re not in a position to doubt them. It’s not our business to act as depots for the long-term storage of other countries’ cultures if these pieces have been seized by law enforcement for the purpose of repatriation.

That’s where we do know and trust each other within the museum sector. That is not always appreciated by the public. There is often talk about the extent to which politicians understand or appreciate culture. I think the answer to that is that all politicians understand how important culture is because it’s the basis of manifestos, ideologies, national education curricula to some extent, and the tourism economy. In my experience, not a single politician is unmoved by the impact objects have on them if you explain what the significance of a given object is. One has to remember that politicians are people too and it’s really a case of making the right connection and showing that culture counts. That’s where the role of museums in bringing in politicians of all sorts, whether in power or in shadow roles is terribly important. We are centers of soft power and centers of neutrality, and we therefore have a very powerful role to play in advocating for the power of culture and speaking across borders as well.

St John Simpson: One of the great challenges for collectors and museums is provenance. We know a number of major collectors in Britain and the United States who have offered us pieces for loan and donations, but they are aware that we can’t accept them unless they follow our due diligence, so for the most part we can’t accept them.

Is it foreseeable there could be safe collections in Yemen, and that it would be possible to have cooperative relationships that would further the goal of sharing objects? Where do you start to heal the system?

St John Simpson: I think that would be amazing if that were to happen. One of the extraordinary initiatives that was announced at the Hermitage last December was what Dr. Mikhail Piotrovsky has done to help establish a conservation laboratory in the National Museum in Muscat, Oman for the conservation of pieces from Syria that have been damaged in the war. That obviously acts as an in-Arab-country conservation training center for pieces that come in and out of Syria. I think that’s quite an extraordinary idea for capacity-building within the region. The British Museum has a big exhibition on Assyria which was just coming to an end so I went to St. Petersburg for the close and the closing conference they were planning. Global events rather overtook us, and we now have an exhibition under lockdown, but that’s the case for exhibitions all around the world at the moment. And the conference was canceled, obviously, but hearing about that initiative came out of that process.

The choice of Oman is quite brilliant. It’s a neutral country. It values cultural heritage. It talks to many of the players within the region and yet has not gotten drawn into regional conflicts. And they have a great new National Museum. I think the choice of that museum and that country is really inspired. I think it offers a way forward into the future for other countries to collaborate through them.

Politicians are often very quick to grasp the power of objects to move people, but they tend to look for someone to blame. Sometimes, there are monsters. In Syria, we’ve seen Hama again and again.

St John Simpson: What we need to do is to try and see the restoration of peace and order as soon as possible and the rebuilding of international and collaborative links through culture and in time it will become evident what really happened there.

History is full of monsters. We can’t tame monsters and we can’t kill monsters but we can outlast all governments. That’s what museums do. The British Museum is about the same age as Afghanistan as a country [Ed. the British Museum was founded in 1753 and the rule of Ahmad Shah Durrani began in 1747], and we have each of us seen a succession of different governments of different complexions throughout our respective histories and yet we talk to their National Museums and they talk to us and we trust each other. That’s the most important thing in the end. We’ve got shared ideals.

How can museums best use their soft power today?

St John Simpson: One very important thing is training. We have two very successful programs. One is the International Training Program, which takes curators every year from different countries around the world. We’ve had curators from Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq and Iran. They’ve gone back to their institutions and are still working there. So that builds on what we do. We get to know them and they get to know our processes. Secondly, we are in the final year of a five-year British government-funded training scheme for Iraqi archaeologists, all professionals. If we can get funding to extend that scheme both in Iraq and elsewhere, we’d like to do that. One of the things we’d really like to do if we can is to think about developing a scheme for Syria. That would perhaps be longer term, sadly, as would be a scheme for Yemen.

What works and what has been less helpful?

St John Simpson: There is a common tendency today to look at bespoke databases and remote sensing. I would suggest caution with both things. I don’t think bespoke databasing is an answer to understanding trade and I don’t see or hear much appetite for that approach among our stakeholders in the host countries we work with.

Their views need to be put forward first. It is by training together on practical issues that we can best move forward: how you record objects, how you pack objects, how you tell genuine things from fakes, how you prioritize what you record. Those are really important curatorial skills and we teach them to our own curators and we try to share that information with our trainees in other countries.

Then you start to hear and see what they want and need. That’s where the needs analysis has to grow from, rather than developing it from sitting around a table in a building in the West and saying we need this database, we’ve got to have that database. It falls down because they don’t trust databases, they don’t have the power to run the databases, they don’t understand the vocabulary behind the databases and they aren’t used to dealing with databases because they don’t use them on a day-to-day basis, at least in the cultural sector. I and a number of colleagues have a real concern about that approach.

Databases and satellite tracking can give you the facts about how many holes there are but that doesn’t tell you what’s driving the digging, or what was found there. You might be familiar with a recent study where they counted the objects and their sizes that had been found in well-documented archaeological sites and compared this to the values of objects of similar size sold at the biggest auction houses and took that as the value of the objects that would have come from looted sites. These things don’t have anything to do with each other. This is what happens when you don’t do field research.

St John Simpson: There is a whole generation of archaeologists now that has got PhDs and got jobs based on using remote sensing because they couldn’t get to the countries on the ground. The problem is it’s like diagnosing cancer with a CT scan. It’s slightly pointless unless you can operate. I totally agree it needs to be followed up wherever you possibly can with ground research. You’ve got to look at these sites.

On the other hand, it could be a tool for law enforcement.

St John Simpson: Yes, and that is something that needs a whole new approach. The Iraqis have got a very well-trained and very intelligent archaeological police service who operate jointly with the Ministry of Interior and the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage. They patrol the landscape, talk to locals, they follow up on any reports of looting, and they protect the archaeologists, museums and monuments.

It seems to me that working with organizations like that and going back to some of those looted sites where there’s a lot of data still there, you could get a much better handle on what is driving the looting and understand the difference between organized and ad hoc digging. From that you could start to manage those sites. Those sites are still full of archaeology; they’re not totally destroyed. You could turn them into training grounds basically, to retrieve data from what are effectively crime scenes. That is a whole new approach that could really be grasped and developed for the good of archaeology, for the good of the national archaeological service and for the police there and abroad. That’s one tremendously exciting way forward that we would like to do ourselves.

In the second part of the interview you will read more about the situation in Afghanistan and what could be really helpful approaches at cultural property issues starting right at the archaeological sites.

This interview was published originally on Cultural Property News.

Don’t miss to subscribe to their newsletter (on top on the right)!

Recently the RAND report also came to the conclusion that illicit trade in antiquities is not such a big market as media used to depict it.