By David Hendin

October 15, 2015 – Shraga Qedar (1933-2015) died in his home in Gvat Shmuel, near Tel Aviv on September 23, surrounded by his six children. Shraga Qedar loved his family, loved his friends, and loved life – every part of it. Qedar had six children and eleven grandchildren. He lived through the Holocaust, escaped from a train taking him to a German concentration camp, made his way to Israel, received a head wound in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, and otherwise participated in the building and development of the modern state of Israel. With very limited formal education, Shraga became one of the most accomplished professional numismatists in the world. He died after a prolonged illness that left him largely incapacitated, although throughout his illness he continued to attend numismatic events and auctions and visit friends whenever possible.

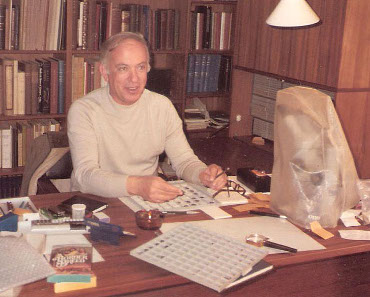

Shraga Qedar in 1982. Photograph by Don Simon.

I first met Shraga in 1975; we were introduced in Jerusalem by our mutual good friend Ya’akov Meshorer. Shraga’s office, a block away from the Israel Museum, was a regular meeting place in Jerusalem. In that office I looked at tens of thousands of coins, drank hundreds of cups of coffee, and had countless hours of lessons on history, numismatics, conservation of coins, and life, with Qedar, Meshorer, Dan Barag, and other fascinating visitors.

Shraga was a demanding teacher. If one could identify a coin or an object, it would simply not meet with his approval unless the person also knew the full account of the history of its period or time of use. Shraga was a great encourager, he often edited my books and articles, and was extremely helpful when I wrote my book Ancient Scale Weights and pre-Coinage Currency, for which he wrote the forward. He also frequently collaborated or worked closely with both Meshorer and Barag, among others.

I often traveled to Israel with Don Simon, our mutual friend from New York. Shraga enjoyed taking us on multi-day trips to various parts of Israel. One winter day around 1980, we drove to Israel’s far north of the Golan Heights. It was pouring icy rain and we were driving on a pitch-black, dirt road. Suddenly Shraga slammed on the brakes. In front of the car was a large cow blocking the narrow road. We got out of the car and noticed, as Don Simon recalls, we were surrounded by several tanks – happily all Israeli. Shraga, who claimed a great sense of direction, turned the car around and headed back the way we came. Within moments we saw a sign that said: CAUTION: Israeli Border Ahead. He had inadvertently driven us past a border crossing and we had been in a shallow no-man’s land headed towards Syria. The “Syrian cow” saved us from an unknown fate. We also took less adventurous trips to the Sea of Galilee or the hot springs near the Dead Sea, and we stopped at sites such as Qumran or Ein Gedi on the way and studied their histories and archaeological remains.

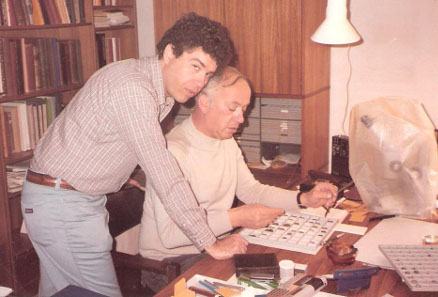

Shraga Qedar with David Hendin in 1982. Photograph by Don Simon.

The Coinage of Samaria in the Fourth Century BCE.

Shraga published two books and more than 20 articles in numismatic journals – a sterling academic record for a person with almost no elementary or secondary education. According to his good friend, the late Dan Barag, Shraga, “autodidact par excellence…furthered his knowledge of ancient history taking advantage of his command of Hebrew, Arabic, German, English, Polish, and Hungarian.” His interest in coins began in the early 1960s when “he happened to find some ancient coins in the sands of Haluza in the western Negev. His attempts to identify the coins convinced him of the importance of numismatic evidence for understanding and improving the interpretation of history,” according to Barag.

Among Shraga’s best-known numismatic accomplishments are the first two volumes ever written on Samarian coins, both co-authored with Ya’akov Meshorer, with whom he often worked and consulted – The Coinage of Samaria in the Fourth Century BCE (1991) and Samarian Coinage (1999). Qedar also discovered the mint of Marisa, a previously unknown mint city in Judaea (1993). Earlier in his career, in 1980, Qedar wrote an article with Dan Barag, “The Beginning of Hasmonean Coinage” which challenged Meshorer’s early theory that the first Hasmonean coins were struck by Alexander Jannaeus and not John Hyrcanus I. Eventually hoard evidence from Mt. Gerizim in Nablus proved the Barag/Qedar theory. Qedar also published pioneering articles on coins struck under Arab and Arab-Byzantine rule.

Qedar also applied his systematic approach to the creation of a series of four catalogs of ancient scale weights; Gewichte aus Drei Jahrtausenden (Weights of Three Thousand Years), conducted by Münz Zentrum Auctions in Cologne, Germany from 1978 to 1983, which remain a standard reference set.

Dan Barag wrote a tribute to Shraga in the Israel Numismatic Journal (2007-08) that was published in his honor. Here is Barag’s telling of Shraga’s early life: “Shraga Qedar was born in Cracow, Poland in 1933. His father, Meir, was an importer and exporter of dry goods and his mother, Navah, had a degree in German culture and literature from the University of Cracow. Both parents were alumni of the local Hebrew gymnasium and Hebrew was the language spoken at home. Their prosperous and happy home life changed dramatically on 1 September 1939, when the armies of the Nazi Third Reich invaded Poland and turned the lives of many millions of people into a nightmare. Shraga, his mother and his elder sister escaped, individually, from a concentration camp in 1942. His father did not survive Auschwitz. Not yet ten years old, Shraga wandered through Slovakia to Hungary and spent 1943-1945 in Budapest, where he witnessed and survived the extermination of the Jews of Hungary,” Barag wrote.

Shraga told me that as a boy he was underfed and skinny. Because of his size he was able to squeeze out of a train car and escape imprisonment in a concentration camp. Because of his blond hair and blue eyes he appeared to be an Aryan. In 1943 Shraga arrived in Budapest, homeless and without money. On the streets he met a woman who brought the boy home to her apartment. She was a prostitute and the 10-year-old Shraga knew that he had to leave the apartment when she had customers. He lived like this until the war ended and Shraga joined the Youth Aliyah program, which would soon take him to Israel. Shraga did not know that his mother and sister had survived, until he met them in the town of Afula, many years later.

Dan Barag continued his tribute: “Traveling with Youth Aliyah, Shraga reached his uncle in Tel Aviv in late 1945 and enrolled in the School of Agriculture at Petah-Tikvah. In 1951-1953 he served in the army. In 1953 he trained in construction and in 1954 he settled in Hazor in the Upper Galilee doing organizational work for the Israel Labour Party. In 1962-1966 he was Secretary of the Worker’s Committee in Afulah in the Esdrawlon Valley – the youngest secretary of a local workers committee in Israel…

“In 1967 he published his first paper, on an unrecorded Umayyad mint at Dar’a (biblical Edr’ei), the capital of the Gilead and Bashan in northern Trans-Jordan, in that period… Numismatics became his main source of livelihood and academic interest…Through participation in international numismatic congresses and extensive travel he was able to make the personal acquaintance of many leading numismatists.”

More pictures of Shraga Qedar are posted on the Facebook page of the Israel Numismatic Journal with a date of September 25 and 24.