by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

June 15, 2017 – Admit it, Lorca isn’t really the first thing that comes to mind when you think about possible stops on your Spain trip. That’s a mistake, because, on the one hand, the city has a magnificent parador, on the other hand, it’s at a comfortable distance to several important centres of Phoenician rule in Southern Spain. Cartagena, for instance, is only a short 100 km away, and that’s driving along the coast…

The parador of Lorca rises high above the city. Photo: KW.

Friday, March 24, 2017

We’re on the way from Sagunto to Lorca – and get lost repeatedly. Or so we thought. After all it’s not that easy keeping in mind that Spain sometimes has parallel highways: one for which you have to pay, and another that’s free but overcrowded.

We arrive in Lorca in the afternoon. Everybody here knows where the parador is, so there are no signposts. We don’t, however, but we’ve stayed in a parador before. So we keep in direction of the city centre. And while we still make our way through the narrow streets, agonizingly slow, a castle high above the city catches my eye. I know instantly: This must be the parador we’re looking for. Fortunately I am right since the drive up to the castle hill is somewhat laborious if you’re not familiar with the intricate right of way regulations of Lorca.

And before you ask why we didn’t turn on the satnav: well, simply because the parador is newer than my car and my satnav doesn’t know it yet.

Visigoths. Sisebut (612-621), Iliocrici (= Lorca). Triens. From Aureo & Calicó auction sale 242 (2012), No. 17 – The hammer price of this extremely rare specimen was 27,000 euros!

I admit it. What drew us to Lorca was actually only its strategically convenient location on the way to the south of Spain. From the top the city looks like many other Spanish cities: Many, many baroque buildings, a good amount of medieval architecture, and a hint of Modernismo. Of course the city’s history reaches far back into the past.

Taifas. Ibn Asli, Emir of Lorca, 1241-1245 AH. Copper-dirham. From Aureo & Calicó auction sale 267 (2015), 2117.

The area around the impressive castle hill has been settled since the Neolithic Age. The Romans were here, the Visigoths, the Arabs, and of course the Spanish. In 1244 Ferdinand III of Castile and Leon captured the city. Lorca became the spearhead in the fight against the Kingdom of Granada and maintained its military and economic importance until far into the 18th century.

Karl IV. Lorca 1 Real 1789. Fourrée. From Aureo & Calicó auction sale 267 (2015), No. 2803.

The downfall only came in the 19th century. On April 30, 1802, the dam of a nearby water reservoir burst and flooded the city. 700 people died. The Peninsula War and a yellow fever epidemic took its toll, even though the number of people heading to Lorca was higher than that of the people who died. Lorca became the holding centre for the many peasants who flew the misery in Murcia. The city was overpopulated and poor. And it has remained poor, judging by its looks. It was hit by a flood again in 1973, by earthquakes in 2005 and in 2011.

Looking down on Lorca. Photo: KW.

Maybe that’s the reason why the inhabitants of Lorca are known for having celebrated Semana Santa with great devotion since the 19th century. Some travel guides even claim that the city has the most impressive procession of all. (You could constantly hear the bands practising, even up here at the parador.)

A reconstruction of the Phoenician merchant ship that was discovered in the harbour of Mazarrón. Photo: KW.

Saturday, March 25, 2017

What a beautiful day! I discovered our first destination, Mazarrón, on the Web, by accident. Usually not my first choice when it comes to looking for attractions. But the Lonely Planet travel guide remains silent when it comes to the Lorca area and back at the hotel we’re met only with shoulder-shrugging when we ask what there is to see in the area. There was a brand new spa, we’re told. Wouldn’t we like to try that?

Phoenician glass bead. Photo: KW.

We don’t. We drive to Mazarrón. Mazzarón was an important mining centre in the Early Modern Period. There are substantial alum resources nearby. And alum used to be indispensable for dying cloth. Which meant that it was tremendously valuable, because woollen and cotton fabric was the most important bulk good until well into the 19th century. And if you wanted to manufacture them, you needed alum, period.

Today alum mining has been long abandoned. Puerta de Mazarrón lives off tourism. It’s one of the many residential areas that are all about the sun, the ocean, and the sunset years. Real estate agents have set up camp in every second office space. Everywhere you look there are the tiniest summer houses, which look like they cannot possibly hold more than a kitchen, a bedroom, and a living room. All blinds are pulled down. After all, it’s too cold to go swimming in the sea, even if the sun is trying its best.

And so is the city administration. It is visibly putting effort into creating an attractive ambience. The traffic refuges have been covered with green artificial turf and they’ve built a small museum. After all Mazarrón has become famous due to the discovery of two Phoenician wrecks.

The museum is easy to find, open (!), and equipped with a friendly lady at the reception. It is a bit lacking in substance, unfortunately, but the few contents they have are presented very neatly. We see a model of the reconstructed Phoenician ship under canvas. There are a few pretty presentation boards with Spanish and English texts. And one corner even features several exhibits that we cannot unanimously identify as either copies or originals.

Basin in which garum was concentrated. I don’t want to know how that must have stunk. Photo: KW.

When we ask the nice lady where one could see the original ships, she is visibly out of her depth. “Still in the sea,” is her guess. She looks at us apologetically and hands us another city map, which informs us that there is another museum right next to the harbour. It houses a Roman garum factory, which I of course have to see.

Garum was the Maggi sauce of Antiquity. It was made from tuna, mackerel, or sardine by immersing the fish in brine and leaving it out in the sun (I don’t want to know how much that must have stunk!!!). The protein disintegrated in the process and the remains were filtered repeatedly until a clear, amber liquid was left over around which the Romans created a hype similar to that around aceto balsamico these days. The garum price, you must know, was determined by the production location, the type of fish, the duration of the degradation process, the popularity of the producer and so on and so forth…

This museum, however, is not that easy to find. We repeatedly circle the right side of the inner harbour until we see the door. We’re lucky, we have exactly 10 minutes until this very door closes again so that the attendant can take his lunch break. But the museum is very manageable so that 10 minutes (plus the 5 minutes that the attendant delays his lunch break for us) are enough.

Cartagena harbour. Photo: KW.

Afterwards we drive on to Cartagena. We don’t have great expectations. Our Lonely Planet guide doesn’t particularly like this city. Which shows once again that you should always form your own opinion and not believe every printed word just because it’s been printed… Because Cartagena is beautiful. Take only the magnificent deepwater port, which was already used by the Carthaginians. It still harbours ships today.

The world’s biggest three-master. Photo: KW.

Of course we’re not talking large container ships here. But at least a warship or two, and lots and lots of yachts. Highlight is the “Sailing Yacht A,” currently the largest sail-assisted yacht in the world, built in Kiel and owned by Russian billionaire Andrei Melnitschenko. It set sail in January 2017 and, according to media reports, is said to have cost 400 million euros.

Punic Spain. Shekel, unknown Punic mint, c. 237-209. Male head with diadem (Hamilcar?), facing right. Rv. Prora facing right, dolphin below. From CNG auction sale, Triton XVIII (2015), No. 301.

It was this spectacular natural harbour and no other which led Spanish general Hadrubal, in 228 BC, to found an emporium by the name of Qart Hadasht (= new city) in the place where Cartagena is today.

Cartagena. AE, 220-215. From Künker auction sale 104 (2005), No. 28.

The location was a centre for the organisation of the trade between Spain and Carthage because the yields from the significant silver mines near Cartagena enabled the Carthaginians to pay the high reparations to the Romans after the First Punic War. I wonder if they already exported olive oil at the time? We don’t know. Under the Romans, however, it was to become one of the most important export goods of Hispania…

Cartagena. Tiberius, 14-37. With Caligula. AE. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 245 (2017), No. 1405.

Speaking of Romans. In 209 BC Scipio Africanus conquered Qart Hadasht. The city became Carthago Nova and remained a major port of export for Spain’s products. The Romans exported not only silver but also garum and the coveted esparto grass needed for the production of baskets, shoe soles, ropes, and fire-extinguishing mats.

Justinian I, 527-565. Tremissis. Spanish mint (Cartagena?), 550-565. From CNG auction sale 100 (2015), No. 286.

We’ll skip the historical digression here. The usual: Vandals, Visigoths – a quick interlude as capital of Byzantine Spain – then Muslims, Reconquista etc.

The entrance to the Museo Nacional de Arqueologia Subacuatic. Photo: KW.

Because all the numismatics here is eclipsed by the national underwater museum, despite Lonely Planet’s characterization, which goes as follows: “You can see old pottery, harsh lighting, and the reconstruction of a Phoenician merchant ship.” As much as I value pointed remarks in general, in this case the statement demonstrates the author’s lack of interest more than anything else. It is unfounded and arrogant in view of the museum’s really well-thought-out concept.

A look into the part of the exhibition which explains the methods of underwater archaeology. Photo: KW.

There are definitely a few highlights, which, however, may not seem as spectacular as they actually are to visitors without a clue. Plus, there is a didactically excellent overview of how seafaring developed from the Phoenicians to the Early Modern Period.

One of the Phoenician wrecks found near Mazarrón. Photo: KW.

So we get to see the originals of the sunken Phoenician ships we’ve already encountered in Mazarrón. (They are, after all, not on the bottom of the sea but have made it into the museum.)

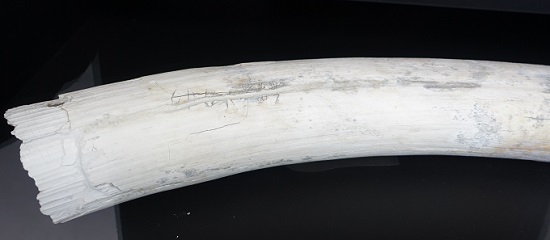

Ivory – not a case for CITES, it dates back to the 7th/6th century BC. Photo: KW.

Also on exhibition: the remains of an ivory cargo, which a Phoenician ship was to transport from Africa to Europe.

Ivory into which the owner apparently carved his name. Photo: KW.

You don’t believe that the ivory is more than 2,500 years old? Well, we know it is, since its Phoenician owner carved his name into it.

A Carthaginian ship compared to a Greek one. Photo: KW.

The presentation of the history of seafaring is very smart. The makers of the museum have reconstructed five true-to-scale cross sections of loaded cargo ships from the relevant epochs: Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Medieval, and Early Modern.

Cartagena harbour in Phoenician and Roman times. Photo: KW.

It is immediately apparent how the size of the ship’s hold multiplies. The three models, which show the harbour of Cartagena in Phoenician, Roman, and Greek time, offer additional information.

Models and showcase on seafaring in Greek times. Photo: KW.

The cross sections correspond to showcases, which feature typical containers for transport, goods, and the money from the respective epoch.

The sinking of the Nuestra Senora de las Mercedes on October 5, 1804.

Undisputed highlight – at least for numismatically interested people – is the contents of a sunken ship. Part of the treasure of the Nuestra Senora de las Mercedes – a manageable amount of 160,000 (sic!) coins – can be found in Cartagena.

Uncleaned coins from the Mercedes. Photo: KW.

The whole treasure comprised many more coins than that. The rest, short of 350,000 coins, have been distributed among other museums and collections.

During the passage the coins were stored in sacks and boxes; the finds testify that. Photo: KW.

The cargo of the Mercedes, by the way, was subject to a drawn-out process between the discoverers of the wreck, Odyssey Marine Exploration, who had also recovered the material, and the Spanish government, which raised claims to the ship’s contents. A US court of appeal in Atlanta declared Spain the legal owner of the coins, whose worth had been estimated at more than 350 million euros. If you’re interested in the reasoning behind that, why Spain of all those involved – and not Peru, which also raised claims – got the coins, read our article reporting on this legal dispute.

In Cartagena Roman excavations can be encountered at every turn. Photo: KW.

But Cartagena has much more to offer still. There is a whole lot of small excavations which you accidentally come across on your stroll around the city, should you not feel motivated enough to look for them systematically. (We definitely are not motivated enough.)

Buildings in the Modernismo style are not exclusive to Barcelona. Photo: KW.

What’s more, a respectable number of splendid Modernismo buildings have been preserved.

And the city is alive! This Saturday countless families are out and about. Tourists there are none. Even for the waiters in our restaurant we seem to be somewhat exotic. And that even though we have lunch at a very Spanish time: shortly before 4.00 pm!

And then it’s back to the parador, which has filled with Spanish couples and families for the weekend. There is just one German car in the huge parking lot and that’s ours.

A little later I finally learn to appreciate our spa after all: While what feels like hundreds of children are shrieking and splashing around in the adjacent warm-water pools behind the glass wall, I have the swimming pool all to myself.

In our next episode we take you to a Neolithic abri, to cave dwellings which make Göreme look old by comparison, and right into the heart of the Spanish olive oil production.

You can find all episodes of the numismatic travelogue “To Spain!” here.