by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

June 1, 2017 – The question where to find the Holy Grail has actually been answered a long time ago: In 1399 Martin I, King of Aragón, exchanged a large golden vessel for the Holy Grail…

Even today the Holy Grail is exhibited in the Cathedral of Valencia. Photo: KW.

… which, according to tradition, had been brought from Jerusalem to Rome by Saint Peter immediately after the Last Supper. It is said to then have been exported to Spain by Saint Lawrence during the Persecution of Christians under Valerian (without export licence! a nightmare for today’s cultural purists!). There it was kept hidden in the monastery of San Juan de la Pena in the Pyrenees during the Moorish occupation before it was brought to Valencia on behest of Martin I. The first news about its worship in Valencia is from 1437!

Holy Grail of Genoa. Photo: KW.

Now cynics may counter that there is another holy grail exhibited in the Cathedral of Genoa…

Calyx of Antioch, around 1900, also referred to as “grail”. Photo: UK.

… that the Calyx of Antioch, exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum today, was also termed grail when it appeared on the market around 1900, and that there is a wooden bowl in the Welsh city of Aberystwyth which has also been treated like one. Well, there are simply more cynics than romantics these days, but even for the worst among you Valencia offers enough other things which make up for the Holy Grail. Let me just say Lonja de la Seda (= silk exchange), to me one of the most impressive secular buildings I’ve ever seen…

Magnificent entrance hall of the Valencia train station. Photo: KW.

Thursday, March 23, 2017

Today we’re making an ingenious move. We’re not taking the train car to get to Valencia, with its 800,000 inhabitants, but the train. There is an urban railway from Sagunto which goes to the Valencia city centre every half hour.

There are plenty of tourists in Sagunto which want to go to Valencia. And of course some of them are particularly thrifty. An Italian matron, accompanied only by a pretty gaunt husband, has discovered that the Spanish Renfe (= train operator) offers something like a mini-group discount. Now she’s forcing two shy Americans and a strange man to form a mini-group with her. Of course she wants the money for the ticket from them before she buys it, … to the cent. While everybody is rummaging around in their bags for change, the queue behind the matron grows longer and the people in it noticeably impatient. After all the train is expected soon … But finally everybody has pulled out the last wanted 5 cents from their wallet and the matron buys the ticket.

The painted tiles which decorate the Valencia train station are simply beautiful. Photo: KW.

We pay the full price! And acquire return tickets which, with 7 euros per person, just about fall within our travel budget. Then we hurry to the platform, where the train is already waiting. And I cannot stop gloating when I see the five scrooges waiting at the wrong platform while our train drives past them to beautiful Valencia.

There are beautiful and on top of that beautifully restored houses from the 19th century. Photo: KW.

If you get the chance to visit Valencia, do it. Valencia is beautiful. It has a big-city feel without becoming unmanageable, beautiful buildings from the Middle Ages to the early 20th century, and something unexpected waiting for you around every corner.

The baroque entrance doesn’t give away which treasures are hidden in the Cathedral of Valencia. Photo: KW.

First we visit the cathedral, of course. It has a little built-in hide-and-seek feature to keep the tourists on their toes. Somewhere this huge cathedral hides two paintings by Goya, and you do want to see those, of course…

A real Goya, even if it doesn’t look like one. Photo: KW.

To make the suspense bearable for you, we’ll say this now: We had to buy the short guide to the cathedral to locate them. I take it that nobody would recognize the two paintings in the Chapel of Saint Francisco de Borja (a grandson of the significantly more well-knwon Borgia Pope, who actually had his origins in Valencia) as Goyas without knowing it.

A look at the dome. Photo: KW.

But even if the Goyas had escaped our attention, there would have been enough to see. For all the Bernese: There is still an arm of Saint Vincent, to which the Bern Minster used to be dedicated, here, even though the remaining bones were transported to Lisbon in 1160.

Coat of arms of Lisbon. Sergio Horta / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Which, by the way, still shows on the coat of arms of Lisbon.

In 2001 Garcia Lledo painted this painting of the martyrs of the Spanish Civil War. Photo: KW.

An inconspicuous chapel behind the altar tells of a very different kind of martyrs. On its walls are two paintings with portraits of many people who have lost their lives in the Spanish Civil War.

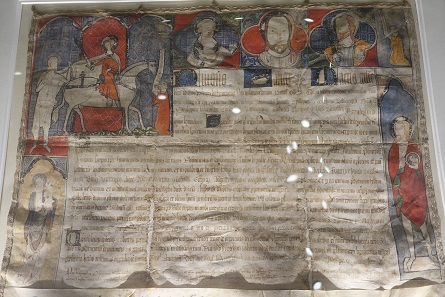

Letter of indulgence, written between 1309 and 1312. Photo: KW.

By the way, the museum of the Cathedral of Valencia is well worth seeing. It does not only exhibit religious paintings, statues, and a replica of the Holy Grail, but also a letter of indulgence. The correct theological explanation of indulgence means this: The many saints of the Catholic Church have collected more good deeds on their heavenly bank account than they would have needed to go to heaven. The Church claims this surplus and forwards it to those who don’t have enough on their heavenly account, of course only against a very small payment made to the earthly account of the Church. (And now tell me again that the Catholic Church doesn’t know economics!)

And if you’re now laughing about the stupidity of the believers back then, take a second to think about today’s climate certificates. Those who buy them don’t consume less energy on their flights or train rides, but they can feel vastly superior to all the other climate sinners.

The archaeological museum is located at the Placa de Decimo Junio Bruto – isn’t that something! Photo: KW.

We could have stayed in the cathedral much longer, but Valencia has so much more to offer still. After all its history dates back to Antiquity. The city was founded as a Roman colony in 138 BC by Decimus Iunius Brutus Galaico. The square at which the archaeological museum is is dedicated to him.

Entrance to the Museo de la Amoina. Photo: KW.

The name of the modern building is derived from the hospital which stood in its place in the Middle Ages: Amoina – alms. This museum, too, is integrated into an excavation, with the playful idea that the light shining on the subterranean rooms does not only fall in through a window glass but also through a large water basin, …

The water basin which creates the light effects on the thermal baths. Photo: KW.

… which is meant to create a fitting atmosphere for the excavated thermal baths beneath it.

A hoard of dirhems from the 12th and 13th century. Photo: KW.

Like everywhere in Spain, numismatics forms a prominent part of the museum. The very first showcase exhibits a small coin treasure from the High Middle Ages.

Skeleton. The arrowheads attest to a violent death. Photo: KW.

The Roman colony was destroyed in 75 BC by Pompey in the war against Sertorius. In the museum, a showcase with weapons and a skeleton with arrowheads still in it testify to this. Valencia seems to have been loyal to Sertorius, which caused Pompey to have the city torn down to its foundations. Only more than half a century later was the area resettled.

Monumental graves from the time of the Visigoths near the burial church of Saint Vincent. Photo: KW.

It was the Visigoths who settled here and expanded Valencia into a local centre.

Visigoths. Suintila, 621-631. Tremissis, Valentia. From CNG auction sale Triton XX (2017), No. 1113.

There are indeed coins from the Visigoths from Valencia, which are, however, almost annoyingly rare.

Leftovers from the Falles of Valencia. Photo: KW.

And that’s it for the museum’s report. It grows louder. A group of school kids enters the excavation site, an Italian travel group joins them, and both are obviously taking great pains to drown out the other. We escape into the daylight, speeding to get out of the museum, and turn two corners. Where we discover loads and loads of flowers, slightly withered to completely rotten, which, after a quick consultation of the web, turn out to be the leftovers from the Falles.

The Falles is a local spring celebration, which we’ve missed, thank God. Because of it, millions of people crowd the city’s streets every year. The stars of the event are gigantic puppets made of wood, plaster, and cardboard, which mock our times – in a similar manner as the floats in the German carnival or the lanterns of the Basel cliques.

The wooden frame for the flower offering, still pretty fresh – with decoration. Photo: KW.

Part of the celebration is a procession in honour of Our Lady of the Abandoned, city patron of Valencia. To that end a wooden construction is built on the Placa de la Virgen, into which all the donated flowers are put. Round about 50 tons of flowers are said to be needed for the enjoyment. And the flower-covered Madonna was still standing around, simultaneously an object of admiration and a background decoration for selfies.

Taifa of Valencia. Abd al-Aziz al Mansur. Dinarius fragment. From Aureo & Calico auction 291 (2017), No. 5.

But back to the history of Valencia. In 714 Valencia became Islamic. And in this time it developed into an international trading metropolis. Articles for export, i.e. paper and silk, leather and ceramics, glass and silver ware, were manufactured locally. After the death of al Mansur, from whom the gold coin depicted above comes, the rule was transferred to small local princes, the most famous of which was probably Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar. We know him as Cid. He ruled Valencia between 1094 and 1099, and the Moorish sources don’t have much good to tell about his rule.

Martin I, 1396-1410. Gulden, Valencia. From Aureo & Calico auction sale 291 (2017), No. 286.

Let’s skip the back and forth between Moors and Christians which began after the death of the “Campeador”. Let’s go straight to the year 1238 when James I founded the Kingdom of Valencia, which was to be dissolved to the Kingdom of Aragon later. Valencia, the capital, was a cosmopolitan city at the time and must have had close to 200,000 inhabitants.

La Lonja de la Seda. Photo: KW.

But people don’t speak of the golden age of the city before the 15th century when the local textile industry and the trade resulting from it made the city very rich (and by that I mean really rich!). We mustn’t forget that canvas and cloth, silk and felt were among the most important trading goods in the Early Modern Period. Everybody needed garments, the higher the social status the more often, the more exquisite, and the more expensive. While many other goods for everyday use were still produced in the own household, cloth manufacturing was not profitable for home production due to the division of labour it required. That’s why the centres of cloth production became the big trading centres of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. And Valencia was one of them.

The Contract Hall at the Lonja de la Seda. Photo: KW.

Just how rich the citizens of Valencia were shows in their palace, which they had built between 1482 and 1548. Never has a more splendid building been erected for the profane purpose of trade. One looked to ecclesiastical models on purpose, giving the narrow-minded clergy the finger. Let them lament how sinful usury is, using money to make money. The rich merchants knew better.

No photo can capture the impression that this incredibly high hall has on a visitor. Photo: KW.

Proof of that is the gigantic banner, written in flawless Latin, whose message confidently testifies to the ethos of the honest merchant and promises him the kingdom of heaven: “I am an illustrious house built in fifteen years. Try and see, fellow-citizens, how negotiation is such a good thing when there is no lie in the speech, when it swears to the neighbour and does not deceive him, when it does not lend money with an interest charge for its use. The merchant who acts this way will prosper galore and at the end he will enjoy the eternal life.”

Exuberant details in every nook and cranny: here a witch is holding one of her cats while the devil is blowing air into the animal with a bellows. Where? Just look for yourself! Photo: KW.

And so there are little moral sculptures everywhere, speaking of the dangers of hell and the rewards of eternal life – just like in a church. We walk around, in amazement, unable to get enough – and once again marvel at the selfie-obsessed people around us who only take pictures of themselves …

A frog, playing the flute. Photo: KW.

… and not of all the endearing creatures which you only see when you look closely. My favourite is a little frog sitting in a lintel and playing the flute.

The hall in which the Tribunal del Mar was seated. Photo: KW.

Suddenly we hear an old German Christmas song – in mid-March, right before Easter. “Es ist ein Ros’ enstsprungen” (“Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming”). I want to join in instinctively but my beloved steps on my foot right in time when he notices that the film, which tells the story of the Lonja, is set to the score of this song. Well, I guess the producers got it wrong this time. They were looking for a song which sounded archaic-medieval and forgot to research its origins. We look around the visitors a little bit and notice many Germans, giving away their nationality by smiling and quietly humming/ singing/ whistling along …

Wooden ceiling of the Tribunal del Mar. Photo: KW.

Just next door to the silk exchange is the Tribunal del Mar, a kind of merchant tribunal, which settled disputes immediately by fast tracking. After all a travelling merchant usually didn’t have the time to wait until the official municipal courts finally bestirred themselves to call a court meeting. Many trading cities had such merchant tribunals. They meant a significant improvement in the legal protection of foreigners and were a real argument in favour of using this trading location.

The highlight for Star Wars fans: Lord Vader’s larger-than-life helmet. Photo: KW.

That day we did many other things in Valencia. We strolled through the 19th century market halls, which have been reopened and revived. We enjoy paella, after all this is where the Spanish national dish is from. And we drive to the Ciudad de las Artes y de las Ciencias, designed by Santiago Calatrava, who, by the way, is also from Valencia. The web lists 33 museums in Valencia. We ignore all of them and drive back to Sagunto. And once again we swear an oath to return to Valencia one more time. At least for a week! It won’t get boring for sure.

The next episode of our numismatic diary brings us to Lorca. I have a stone-age cave to offer, remnants of two Phoenician shops, and 600,000 coins. Curious?

Of course we will make all episodes of the numismatic travelogue “To Spain!” available here.