by Ursula Kampmann

October 3, 2013 – Marcel Ebnöther was certainly a very modest man. Before he died in 2008 he had taken care that his collection would find a new home in the Museum zu Allerheiligen / Schaffhausen.

The Entrance of the Ebnöther collection’s new display. Photo: KW.

Searching on the internet for Marcel Ebnöther one retrieves only very few information. You learn that the collector was born in 1920 and founded the adhesives specialist company Ebnöther AG in Olten which gave him the means to finance his passion. Marcel Ebnöther travelled much, particularly to Latin America. And he started to ask himself to what degree certain phenomena developed similarly or completely differently in distant cultures. His inquiring mind is testified by his collection comprising 6,000 objects and by his archaeological diaries in which he describes skilfully and in detail his impressions in writing and with images.

A view into the exhibition. Photo: KW.

From now on almost a tenth of all the objects he gathered can be visited in a new permanent exhibition in the Museum zu Allerheiligen. A very good reason for taking the train to Schaffhausen when you attend an auction in Zurich the next time. Unfortunately Marcel Ebnöther was not interested in coins, but nevertheless the material on display touches upon all those interested in the cultures of Mesopotamia, Greece, Italy and – above all – pre-Columbian America.

Peru. Cupisnique. Vessel shaped as a hunter with his prey; made around 1500 to 700 BCE. Photo: KW.

The first room is dedicated to the collector’s concept. Marcel Ebnöther compared the formation of the various cultures he was dealing with.

Taranto(?). Statuette of a ram-bearer. 2nd half of the 5th to 4th century BCE. Photo: KW.

He was delighted by such resembling images like these of an ancient Peruvian hunter carrying his prey home and a shepherd from Magna Graecia taking a ram on his shoulders.

Portrait of the first Roman emperor Augustus. Photo: KW.

The timeframe of his comparisons in the Old World spans from a crouching woman of the Syrian Halaf culture (c.5500 BCE) to the Roman Imperial time represented here by a portrait of the emperor Augustus. The items from the New World start with ceramic figures from Ecuador made around 2000 BCE and end with the fall of the Inca empire in 1532 CE.

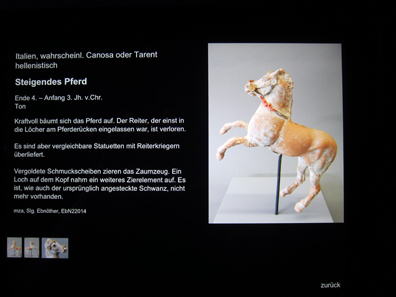

Taranto (or Canosa?). Rearing horse, between the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd century BCE. Photo: KW.

The quality of the objects is really impressive. Let’s cite as an example this wonderful rearing horse made of ceramic and probably produced in Taranto. The rider, once fixed in the holes on the horse’s back, is now lost.

Taranto. Didrachm, before 300 BCE. From Gorny & Mosch 195 (2011), 14.

Were he still there, one could see even better the resemblance to the little posterior coins from Taranto.

Description table. Photo: KW.

Most objects are described via touchscreen. Every showcase has one touchscreen that offers a central start page leading to other views and magnifications giving detailed information in various languages.

Mesopotamia. Ox-drawn cart, 2nd half of the 3rd millennium BCE. Photo: KW.

Animals and human beings, arms and warriors; this title would fit for the second exhibition room. Or to say it in a different way: Life in peace and life in war. The highlight in this room is the miniature of an ox-drawn cart with huge disc wheels as it may have served as status symbol during funerals in Bronze Age Mesopotamia.

Nazca / Peru. Bowl featuring fish decor, 2nd to 7th century CE. Photo: KW.

Fishing was another topic common of many peoples as for example the Nazca, who painted their staple food in a stylised manner on magnificent bowls.

Veracruz / Remojadas. Two warriors, 6th to 7th century BCE. Photo: KW.

War received much more attention in the art, though. Wearing warpaint and armed with clubs and shields these warriors from Mexico terrify their enemies.

Etruscan statuette of a warrior, probably from Umbria, 5th century BCE. Photo: KW.

In comparison this statuette of an Etruscan soldier with helmet, plate armour, shield and greaves captured in the moment of throwing the spear appears rather drab.

Chimú / Peru. Vessel with ruler holding a head trophy. 11th to 15th CE. Photo: KW.

Apparently Marcel Ebnöther was fascinated by the head cult and human sacrifice as practiced in pre-Columbian America. At least quite some items are dedicated to this subject.

Colima / Mexico. Pot in duel shape. 2nd to 3rd century CE. Photo: KW.

Here we see a victorious warrior who is preparing to behead a defeated man with his hatchet. Skulls whether captured in a ritualised or a real fight were later exposed on special scaffolds.

Nayarit / Mexico. Funeral scene, 1st to 5th century CE. Photo: KW.

Another group of themes consists of death, funeral, religion and conceptions of the afterlife. Here we can see an impressive funeral scene of the Nayarit people. On a village square, limited by two houses, the funeral procession is forming. The dead is a wrapped mummy carried by six men. If you look attentively you will recognise figures around this event who transfix their cheeks so as to sacrifice their blood on this occasion in cups.

Vowing women. Left: Etruscan work, around 350 BCE; right: Syria, around 2000 BCE. Photo: KW.

These two women stand for appeals to the gods although more than 1,000 kilometres and over 1,000 years separate them. The gesture, though, is always the same: A gift in her hand the woman approaches the gods.

Minor Asia. Metal fitting of bed frame bearing a Greek inscription. 93 BCE. Photo: KW.

The next room is dedicated to the achievements of culture, above all script, then dancing and music. From a cylinder seal to a small cuneiform tablet to this remarkable object we can follow the development of script. These Greek letters once adorned a bed with a silver fitting which may have been a votive gift in a sanctuary of Herakles. The inscription names the commissioners, Aphrodisios and Protion, as well as the executive craftsman, Pausanias, the exact date, year 205 of the Seleucids’ era, and the price – unfortunately not given in the description on the touchscreen. And my Greek is not good enough to decipher it. But maybe a reader of CoinsWeekly steps into the breach …

Inca quipu, 15th to 16th century CE. Photo: KW.

Even more romantic is this quipu, a sort of knotted string which was employed by the Incas to record information. At the latest since Karl May’s ‘Das Vermächtnis des Inka’ (The Legacy of the Inca) all adventurous readers in Germany know the purpose of this particular form of writing.

Vulci(?). Etruscan incense burner with dancer, around 500 BCE. Photo: KW.

The collector seemed to enjoy particularly demonstrating how much dancing and music had spread all over the world. Here we see an example from the Etruscan world, a world, apparently much attached to dancing. This young man does not bear anything except a kind of crackowes. In his right hand he holds an incense bowl whose cup is now lost.

Teotihuacán / Mexico. Dancers, 3rd to 5th century CE. Photo: KW.

These stylised but incredibly modern-looking statuettes perform virtually a sort of character dance. Around the temple of Teotihuacán innumerable heads of such small ceramic images were discovered. Probably they were once ritually broken during a ceremony.

The last exhibition room. Photo: KW.

The last exhibition room is a real treasure room. Here the most precious objects are housed.

Urartu. Ensemble of ceremonial buckets, around 810 BCE. Photo: KW.

For the very first time the complete silver finding from the tomb of the Urartian prince Inuspua is on display.

Ceremonial bucket with figural decoration, around 810 BCE. Photo: KW.

Seven ceremonial vessels, one of them with magnificent figural decorations another with an epigraphic dedication, certainly will impress the visitors.

Teotihuacán / Mexico. Mask with earlobe disks. 3rd to 7th century CE. Photo: KW.

All these stakes which served for adorning the ears of the ancient American peoples forestalled a modern custom. The modern descendants, however, must buckle down with much more dedication until their earlobe slits will be so dilated that they could wear these marvellous creations:

Chimú / Peru. Two earlobe disks. 11th to 15th century CE. Photo: KW.

Huari / Peru. Earlobe disk. 6th to 10th century CE. Photo: KW.

Chimú / Peru. Earlobe disks with feather motifs. Photo: KW.

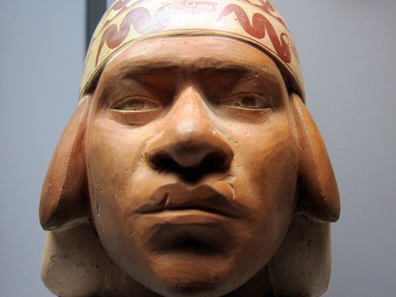

Moche / Peru. Portrait-shaped vessel, 5th to 7th century CE. Photo: KW.

Even more interesting from an art historical point of view is this vessel of the Moche culture portraying a person known to archaeologists as ‘cut-lip.’ Thanks to the characteristic lip scar that we see on over 40 known images, we know that the Moche vessels feature real persons. Our cut-lip clearly grows old on the jars. Here we see him in his late teens.

Nazca / Peru. Warrior with head trophies. 2nd to 7th century CE. Photo: Museum zu Allerheiligen.

Let’s end with this splendid Nazca warrior, a work of art en miniature measuring in height not more than 4.5cm. This item is composed of not less than 35 single pieces!

On November 7, 2009 the renovated Ashmolean Museum opened again. At this time the cross-cultural presentation of topics like ‘the Human Portrait’, ‘Reading and Writing,’ or ‘Money’ was praised as the most accomplished achievement of modern museology. It is remarkable how the echo to unconventional creative thinking changes when a mass of highly decorated researchers opt for it. In 1999 professor Peter W. Haider from Innsbruck begun the preface of the catalogue of the Ebnöther collection redacted and edited by the collector himself with the following words: ‘It may surprise the visitors of the museum or even irritate them in the first moment that the objects on display are not presented, as usually, separated according to cultural spheres but arranged to subjects and therefore objects originating from different cultures are united in one single showcase.’

No, Mr Haider, I am not surprised, but I am astonished that a collector like Marcel Ebnöther stayed true to his concept notwithstanding all critics from the researchers’ side; and I am irritated that he did not receive more attention for his innovative concept of how he presented his collection.

The objects gathered by Marcel Ebnöther and now housed in Schaffhausen are world-class objects. No doubt, this exhibition is worth an even much longer detour than only one hour by train – coming from Zurich.

You can learn more about the Museum zu Allerheiligen and its new permanent collection here.

You may listen to an audio clip (in German) of ca. 3 minutes on this subject here.