by swissmint

translated by Katja Protsiva

Since 1955, the Swiss mint was striking gold coins on a large scale, as you can read in detail in chapter 1 on Swiss gold coins for 25 and 50 francs. Read here why the coins did not come into circulation after all.

Why the coins were not issued

It was not because of the aforementioned artistic objections that the coins were not issued in the end. It was rather due to monetary reasons and market policies.

The 25- and 50-francs-coins were not minted for circulation, because at that time one was a long way from a gold circulation currency everywhere. The intention was rather to absorb and tie up liquidity at the capital market if necessary. But certain conditions needed to be met for that. The general situation needed to present a level of liquidity that would jeopardize the purchasing power of the money (danger of inflation). For that, the price for gold had to be close to the parity value of the gold, which corresponds to the face value of the coins. As it was planned that the people should not actually use the coins but put them aside.

After a large number of old gold coins was handed in for hoarding in 1955, the conditions were not met anymore in 1956, resulting in the means not being everywhere equally available on the market which lead to a slight rise of the interest rate. Issuance of coins would have intensified this development. Besides, the formerly issued Goldvreneli were traded with an agio of 19 to 25 % by then. If the National Bank would have issued the gold coins corresponding to their face value, they would have become ventures instead of being hoarded, which was unwanted. Later, a rise of the price for gold lead to the coins’ intrinsic value exceeding their face value. Therefore, it was not possible anymore to issue the coins corresponding to their face value and it was illegitimate to issue the coins for a higher price.

Longed for shelf warmers

Collectors repeatedly encouraged the issuance of the gold coins. In the context of the planned minting of a gold coin for the 700-years-anniversary of the Swiss Confederacy (CH-91), the matter was review and dropped as before. On the one hand, it was due to legal regulations of the Federal Constitution and the monetary act and on the other hand, due to economic and monetary concerns of the National Bank.

The following reasons argue against the contribution of the coins (note from 4 June 1987, from vice director Bretscher, legal service at the Federal Finance Administration to Federal Chancellor Stich):

- First, the questionable coins were not property of the Federation but part of the currency reserve of the National Bank. Due to legal regulations, the bank was only allowed to issue the coins for a price corresponding to the legal money rate (gold parity). Since that was about five times lower than the market price, the National Bank was prohibited to sell.

- If exchanging gold coins (Swiss National Bank) for bullions (Federation), the Federation would have to obtain the money, which had to be paid to the National Bank, at the market. So by selling the gold coins, it would have only gained the numismatic overvalue, which was difficult to estimate in advance. But for that, the monetary act would have to be changed, since it dictated issuance of coins for the face value. That was impossible, because the gold value of the coins by far exceeded their face value.

- Furthermore, the issuance of the gold coins was impeded by serious economic and monetary objections by the central bank. It feared that if selling the coins, resources from investments and saving books would be taken and become part of the economic cycle, which could lead to an inflation. Additionally, a great foreign demand would make the exchange rate of the Swiss franc rise.

The partial revision of the monetary act from 16 December 1997, finally allowed to issue coins for more than their face value. 15 August 1997, Federal Chancellor Kaspar Villinger sent a request to the National Bank in which he suggested to trade the gold coins for the respective amount of fine gold and sell them as bullion coins. The request was denied because of mostly political reasons. Due to the then heated debate about the National Bank’s gold transactions during the Second World War, the central bank suggested to hold off issuing the coins until the historic reappraisal was advanced enough to implement such a project without fanning the flames even further.

The revision of the federal constitution from 18 April 1999, legally severed the link between the franc and gold, which was implemented by the new monetary reform and the Payment Instrument Act from 22 December 1999. With that, the last legal obstacle for the issuance of the gold coins was overcome. Consequently, Swissmint planned to issue the coins and bring them to market. The idea was to issue a limited amount of each motif and year. The rest of the edition would have to be melted down in order to preserve a sufficient interest in the coins, which would have cost millions. Since the profit from the sale would have not even closely covered the cost of the melting down, neither Swissmint nor the National Bank were interested in selling them. Therefore, the gold coins were not issued at that moment.

Straight into the crucible

In the course of 2006, the National Bank started the melting down of “not marketable pieces” into ingots without consulting Swissmint. According to the Annual Reports 2006 to 2008 (section 4.2 Notes to the income statement and balance sheet, item 08 Gold holdings of the Annual Report SNB 2006 (23.02.2007), page 102, 2007 (29.02.2008), page 112 und 2008 (27.02.2009), page 134), the following amount of gold coins for 25 and 50 francs was processed:

| date | 31.12.2005 | 31.12.2006 | 31.12.2007 | 31.12.2008 | total |

| fine gold coins holding, tonnes | 175,200 | 160,000 | 91,600 |

39,000 |

* |

| reduction fine gold holding, tonnes | 15,200 | 68,400 | 52,600 | 136,200 | |

| reduction gold holding, 0,900, tonnes | 16,889 | 76,000 | 58,444 | 151,333 |

Remainder coins in fine gold according to the Annual Report SNB (composition unknown)

Except for 20,000 pieces of each motif and year (= 914.5 kg fine gold) all coins were melted down, according to the Swiss National Bank. This should ensure that “there would be enough of those (art-) historically and numismatically valuable coins preserved.” But they were not issued. Accordingly, there is only nearly one tonne of 25- and 50-francs-coins left out of the remaining 39 tonnes. It is unknown of what the other 38 tonnes consist. But it is assumed that it must be Goldvreneli from the year 1949. The newspaper Helvetische Münzenzeitung 10/1975, page 200 wrote about it: “The National Bank owns … also a large part of the 20-francs-Goldvreneli of the 10 million (pieces) mintage from the year 1949.”

The Swiss National Bank commented on the reason for the melting down: “Since the sell of half of the gold reserves of the Swiss National Bank in the years 2000 to 2005, those gold coins were a substantial part of the remaining gold holdings. In order to assure easy disposition of that part at any time, the board of directors decided to melt down the greater part of the coins into customary gold ingots.” Apparently, the price for gold which rose massively since 2006, made the melting down of the coins seem profitable as well.

In the program Espresso at radio DRS on 6 March 2009, speaker of the National Bank Werner Abegg explained the reason why the National Bank had no interest in keeping such a large hoard of gold coins in the following way: “We need to have gold holdings of the state in the shape of ingots, because this is at best what can be traded with other central banks in situations of crisis.”

Description of the coins

The 50-francs-coin

50 francs

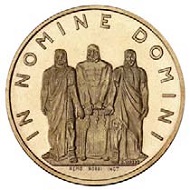

Obverse: Die Drei Eidgenossen by Vibert with the legend IN NOMINE DOMINI (Latin, In the name of the Lord = beginning of the Federal Constitution). On the bottom right at the pedestal of the monument is the name of the creator J. VIBERT and at the bottom in the middle is the name of the artist REMO ROSSI SCULPT.

Reverse: In the middle the face value FR 50, below that, the Swiss cross. Legend CONFOEDERATIO HELVETICA, at the bottom in the middle the year and the mark B.

Edge: milled marginal inscription DOMINUS PROVIDEBIT surrounded by 13 stars.

The 25-francs-coin.

25 francs

Obverse: Wilhelm Tell with crossbow by Hodler with the controversial legend IN ARMIS LIBERTAS ET PAX (Latin, In arms freedom and peace). On the bottom right is the name of the painter of the model F. HODLER PINX and in the middle is the name of the artist REMO ROSSI SCULPT.

Reverse: In the middle the face value FR 25, below that, the Swiss cross. Legend CONFOEDERATIO HELVETICA, at the bottom in the middle the year and the mark B.

Edge: milled marginal inscription DOMINUS PROVIDEBIT surrounded by 13 stars.

Technical data and mintage of the two gold coins in summary

Artist: obverses by Remo Rossi, Locarno; reverses by Battista Ratti, Malvaglia

| mintage, not circulated | |||||||

| motif | face value | alloy | weight | diameter | 1955 | 1956 | 1959 |

| Rütlischwur | 50 franc | gold 0,900 | 11.290 g | 25 mm | 2 M | 2 M | 2 M |

| Tell with crossbow | 25 franc | gold 0,900 | 5.645 g | 20 mm | 5 M | 5 M | 5 M |

| total | 7 M | 7 M | 7 M | ||||

Brief profile of both artists

Remo Rossi

Sculptor, citizen of Arzo, born 27 September 1909 in Locarno, where he also went to secondary school. 1926, Lucerne School for Arts and Crafts. From 1927 to 1932, studies with Ernesto Bazzaro in Milan. Studies of architecture and anatomy at Accademia in Brera. 1933 to 1935, Paris, studies at Académie Scandinave with Ch. Despiau and at Ecole nationale de Beaux-Arts. 1936, return to Locarno. Extended travel through Europe and Mediterranean countries. 1945, becomes member of the Swiss Federal Art Commission.

His artistic work includes sculptures, statuary art, reliefs, Percent for Art, drawings and medals. Numerous national and international exhibitions. Remo Rossi died 30 December 1982 in Bern.

Battista Ratti

Sculptor, citizen of Malvaglia, born as son of emigrants on 25 February 1896 in Milan. At the age of 13 he trained to be an engraver and goldsmith with G. Beretta, an artisan from Milan. 1915 to 1919, studies at School for Applied Arts in Castello Sforzesco in Milan, then until 1923 at Accademia Belle Arti, Brera. Until 1930, he attended classes with sculptors E. Pellini and E. Bazzaro in Milan. He lived and worked alternately in Milan and in his father’s birth house in Crana in Tessin. His artistik work includes sculptures, monuments, gravestones and Percent for Art. Numerous national and international exhibitions. Battista Ratti died 31 December 1992 in Crana.

Sources:

- Die Woche, date unknown, probably 1955

- Sunday paper of Basler Zeitung 16.9.1956

- Internal documents

- reports of SNB 2007-2009