by Ursula Kampmann

May 30, 2013 – There’s not much left today to see of ancient Phocaea, but ancient ruins aren’t necessary to bring the residents of Izmir out of the city and to the seaside. In addition to visiting Phocaea, we also visit the ancient Sardis in this chapter, birthplace of coinage.

Friday April 26, 2013

We were exhausted after a long day by the time we found our accommodations in the small Hotel Erguvan / Foca last night. But the elaborate breakfast rejuvenated us, and so we decided to drive to Sardis instead of immediately taking a day off. It took almost two and a half hours on the highway to drive inland, past Manisa (= Magnesia ad Sipylus). While Manisa is now quite an impressive city that, according to its place-name sign, has grown to nearly half a million inhabitants, the places that were once the capital of the Lydian kingdoms are now just a few farms. The long convoy of buses, however, ensures there’s no way you can miss the two excavations that can be marvelled at in Sardis.

View of the “Marble Court,” part of a Roman bath. Photo: KW.

We were in luck. We only had to share the ruins with one group from Austria.

Lydia. “Valvel.” Trite. Gorny & Mosch 203 (2012), 235.

Where do defining innovations originate? Certainly not in places where people are happy with themselves. No, rather it’s in places where borders rub up against one another, where people with different experiences and skills collide, that knowledge is exchanged and something new is created. And similarly, it was the border area between the Lydian and Ionian cultures that the idea to undertake a miniature electrum ingot with an image came about. Isn’t it sort of irrelevant whether it was the Greeks or Lydians that were responsible for the idea? It occurred through different cultures coming into contact. Because one thing should be clear: Even though nowadays we sort the Lydian coins into the ‘Greek’ section as a matter of course, the Lydians were a completely different people who, through their depiction in the work of Herodotus, merely seem like a particular variant of the Greeks to us.

Lydia. Indeterminate king. Trite. Gorny & Mosch 203 (2012), 236.

The Lydians came from somewhere in Anatolia and had both their own language and their own writing system. They had their religion, which exerted a strong influence on later cults of Asia Minor. A goddess of fertility was interpreted by the Greeks as Kore, the god controlling lightning and rain mutated into Zeus holding the double-headed axe. And the mother of the Gods on her lion throne is likely to have strongly influenced the image of Cybele.

And at some point, at a date that isn’t certain, the Mermnadae took control of the kingdom. Gyges, Alyattes, even Croesus – the only reports we have about their lives are those of Herodotus, and although the stories are gripping and well told, the Italian proverb ‘Se non è vero, è ben trovato’ still applies.

Map of ancient Lydia. Source Wikipedia. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Lydia_ancient_times-de.svg

The fact that the Lydians conquered large parts of Asia Minor, however, is verifiable. And this would obviously have brought them into close contact with the Greeks. How it then came to the first coins is a matter being very actively discussed these days, most recently at a colloquium in Jerusalem, which we reported on in detail in CoinsWeekly.

Lydia. Croesus. Heavy stater. Gorny & Mosch 207 (2012), 366.

Whatever the case may be, the staters featuring the lions and bull, the first coins that were manufactured from artificially refined gold and silver instead of electrum, are associated with Croesus. Gold and silver staters were a crucial step on the way to a currency that could simultaneously serve as a universal measure of value. And this new medium was useful, so much so that the Persians kept the stamping of the coins of Croesus (if you cross the Halys, and so on …), and then created their own darics and sikloi later on based on the Lydian prototype.

Achaemenides. Daric. From Künker auction 216 (2012), 528.

And with that, Sardis became Persian. The city still remained an important centre of highly differentiated handicrafts, and was famous for its fine fabrics. Elaborately coloured Lydian yarns were widely bartered.

Detail from the Apadana of Persepolis. Plaster cast in the British Museum. Photo: UK.

It’s not for nothing that the famed Apadana from the palace of the Great King in Persepolis depicts a delegation from the satrapy of Asia Minor, with balls of wool and folded garments. By then, the population in Sardis is likely to have mixed heavily with the neighbouring Greeks, and this mixing would have been further strengthened when the Greeks conquered Lydia at the end of the 5th century. The Peace of Antalcidas put an end to all battles in Asia Minor, but at the same time conceded reign of the entire area to the Persian king.

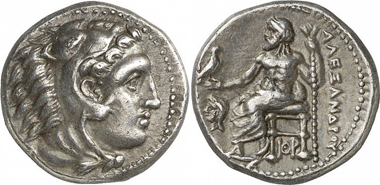

Sardis. Drachm of Alexander III, 334-323. Gorny & Mosch 191 (2010), 1303.

Alexander conquered Sardis on his campaign. Afterwards, the city fell first to the Seleucids, and then to the Attalids, who, in turn, bequeathed it to Rome.

Homonoia stamping from Pergamum and Sardis under Augustus. Gorny & Mosch 191 (2010), 1789.

From then on, Sardis shared the fate of the provinces – it became, like Pergamum, neokoros, so guardians of an imperial temple under Augustus, which afforded it a prominent status in the provinces.

Tiberius. Sestertius, 21/2 on the occasion of the rebuilding of the Province of Asia. Inscription: CIVITATIBVS ASIAE RESTITVIT. Lanz 147 (2009), 248.

In 17 AD, Sardis was devastated by an earthquake. For the next five years, Tiberius exempted the city from all tax payments and contributed 10 million sestertii for its rebuilding. In Byzantine times, Sardis gradually lost importance. It stood in the shadows of Magnesia ad Sipylus, which remained by far the more important metropolis under the Ottoman Empire. It was only in the 20th century, with regular excavations led by Princeton and Harvard that Sardis moved back into the spotlight. Thanks to the superb reconstruction, these ruins are now amongst the most impressive sites in Turkey.

Byzantine bazaar. Photo: KW.

And passing a Byzantine bazaar …

Synagogue. Photo: KW.

… you get to the synagogue. It’s said to date back to a Jewish community that had arisen under Antiochus III (223-187). He had convinced Jews from all over the then known world to come to Sardis. In fact, the historian Flavius Josephus quotes a decree by the Roman proquaestor from the years 50/49, in which the Jewish community as well as a common place, likely the synagogue, are mentioned.

Marble ornament from the synagogue. Photo: KW.

Its magnificent decor and features make the Sardis synagogue the most impressive ancient synagogue remaining from the Western Diaspora. Incidentally, with the decline of the city, the community appears to have relocated to Manisa, as there was a large synagogue there in Byzantine times. It drew many of the Jews who had been expelled from Spain. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were around 2,000 people of Jewish faith living there. They had their own infrastructure of institutions and buildings. When much of it was destroyed during the Turkish War of Independence, the Jews left the city, many of them going to Israel and the USA. Today there are no remaining Jews in Manisa.

Detail from the reconstructed Marble Court. Photo: KW.

From the synagogue, you reach the marble courtyard via a yellow bridge. The Marble Court is a portion of the formidable wall that once surrounded the palaestra of the gymnasium. When you direct your gaze upwards, the many small-scale details are baroque-like. I would have gladly sat there quietly on the steps, just soaking in the architecture, but a trio of females caught my attention. An older woman (quite portly), two daughters (quite pretty, but also very aware of it) and a camera, playing leading roles against the backdrop of Sardis. For a while I just sat there and got irritated at how walls and capitals were climbed and mounted without any regard for potential damage, all in an attempt to capture the so-called beauties in the right light. But when one of the two tried to scale an approximately 4 metre high fragile column in her running shoes, I lost it. I let them have it. And when I want to be loud, I can be loud. The three of them looked horrified, as did the other tourists and their Turkish tour guide. But it worked – the three fled immediately.

Still life with doghouse. Photo: KW.

Unfortunately, we ran into the three women plus camera at the second excavation at the Temple of Artemis. But as soon as they saw me, they scarpered off – as annoyed as I had been – and took their photos elsewhere. One of the group members approached me for this, saying they were just girls and that one shouldn’t be so harsh. I saw the matter quite differently, and let him know it as well.

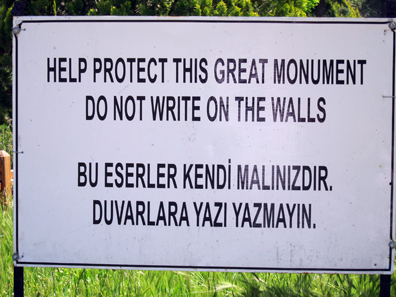

A futile attempt to deal with ignorance. Photo: KW.

This sort of ignorance is universal. People have a tendency to destroy things because they’re too short sighted and foolish to respect the past, and take themselves too seriously. Anyone with half a brain has the choice to either put up with this type of ignorance and lack of respect out of laziness, or to fight back and stand up for what they believe in.

Evidence of ignorance at the Temple of Artemis. Photo: KW.

If we don’t fight back, ignorant people destroy our heritage of humanity without so much as batting an eye. But those who decide to do nothing are just as guilty as those doing the destroying. My lecture certainly didn’t make me any friends. The somewhat older Austrian moved away and the three Graces called out a ‘we have enough pictures!’ and left the area. Two children climbing columns got off of them. Well … ancient ruins seem to have to withstand quite a lot …

View of the Temple of Artemis from above. Photo: KW.

At any rate, we still enjoyed the wonderful view of the Temple of Artemis.

Column capital. Photo: UK.

The sheer size of the temple really only hits you when you stand next to one of the column capitals. After all, this temple is one of the four largest temples in Asia Minor. Construction on it began at the end of the 4th century, and there was a further phase of activity in the 2nd century, but the temple still wasn’t finished. Construction continued under Antoninus Pius, as the deified Faustina was to be worshipped here along with Artemis.

Temple of Artemis, the Tmolus Mountain in the background. Photo: KW.

You can see the Tmolus Mountain beautifully in the background, whose gold brought the Lydian kings their incredible wealth.

The Pactolus River. Photo: KW.

The Pactolus River flows past close to the Temple of Artemis. And it was a great feeling to be able to stomp through the mud completely on our own and dream of the tremendous gold found there (that you wouldn’t have been able to remove or keep anyway).

We drove back. It was too hot to look at any more. Naturally we had considered visiting Usak. After all, part of the great heritage of mankind, the so-called Karun Treasure, is housed in this (in this part of the world) completely unknown city. It’s become known through hundreds of thousands of people having viewed it for some years in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Now after being returned, it sits in a small city another 133 kilometres inland from the already remote Sardis. Google Maps had told us that on these roads we could expect a driving time of 2 hours and 8 minutes. Then it would have been between 4 and 5 hours back to Foca. We decided that this wasn’t worth even the most beautiful of golden treasures, even if, following the investigation of the theft of 2006, all objects are said to be back in the museum to view. CoinsWeekly reported on this as well.

Saturday April 27, 2013

After a quiet evening and a mediocre dinner in a seafood restaurant in the little harbour, we enjoyed a day off – which is to say, we didn’t drive hundreds of kilometres, but instead toured the sights of the place we were staying, Foca.

Bay of Foca. Photo: KW.

Phocaea is said to have been founded in the 8th century BC. Whether it gets its name from the Phocians, who settled there under Athenian leadership, as is transmitted by Pausanius, or comes from the Greek word for ‘seal’ (= Phoka), remains undecided.

Municipal coat of arms. Photo: KW.

In any case, the seal still dominates Phocaea’s cityscape today, be it in the coat of arms …

Detail on a public building. Photo: KW.

… as a small detail on a public building …

Statue. Photo: KW.

… or as a statue of questionable artistic value on the boardwalk. Seals are ubiquitous in the city; which, by the way, is not because in Foca, this is how they appreciate the ancient heritage, but rather that it has one of the last colonies of the rare Mediterranean monk seal. Access to their colony on the Siren Islands is in fact prohibited, but nonetheless, highly lucrative pleasure boat rides are offered in Foca that let you take a look at the shy creatures. According to written figures, there are currently only 350-450 individuals still in existence, making the Mediterranean monk seal one of the rarest species of mammal in the Mediterranean.

Phocaea. Hekte, ca. 625-622. Lanz 151 (2011), 471.

We spared ourselves this. After all, as coin enthusiasts we had already seen hundreds of seals on the coins of Phocaea.

Phocaea. Hekte, ca. 520-500. Lanz 149 (2010), 196.

Among them was one that captured the image of the three seals playing considerably better than did the statue on the boardwalk. But back to the topic at hand …

The men from Phocaea travelled on their ships to the end of the known world of the time. Herodotus writes that they made it all the way to Spain and impressed the king there so much that he asked them to settle in his country. Alalia on Corsica, Emporiai and Rhoda in Spain, and especially Massalia, predecessor of what is today Marseille, are all said to have been founded by Phocaean colonists.

Time and again, Greek authors stylized Phocaea as a great battler against the Persians: Residents would rather have left their city than suffer under the yoke of the Persians. Well, a few may have fled to the colonies, but there were still always enough people available to take part in the Ionian revolt. Under the command of a man from Phocaea, the fleet of the Ionian cities was defeated. Phocaea survived the defeat, and even remained so wealthy that it was able to pay dues of two talents a year after joining the Delian League.

Phocaea. Hekte, 327. Künker 182 (2011), 298.

For numismatists, Phocaea is especially interesting, as it’s the only city for which epigraphic evidence of a monetary union, namely with Mytilene, exists. There, a stela was found that was not erected until around 400 BC, but whose text records circumstances and conditions that had existed since the end of the 6th century. This inscription specifically states the pace and regularity with which Mytilene and Phocaea were to conduct their minting, and in particular, in which alloy. Most of the text addresses the control mechanisms and penalties that were intended to prevent misuse (Perhaps the EU should have taken a closer look at this contract before laying out the regulations of its monetary union).

Remains of the Greek theatre. Photo: KW.

Considering the significance Phocaea once held, the archaeological remains are rather scant. There’s a Greek theatre just outside the city.

Cybele Sanctuary. Photo: KW.

The Genoese fortress is said to have two preserved cult alcoves for Cybele.

Taskule. Photo: KW.

And just outside the city is a monumental stone grave hewn out of the bedrock, which is referred to as Taskule.

Foca harbour, with the Genoese fortress in the background. Photo: KW.

This very touristy city even has an (open) tourist information centre where we picked up an extensive city map with historical comments, as well as information about the nearby Izmir and a 47-page thick treatise on the ‘Events of 1915,’ written by a Professor PhD, and printed at the expense of the Turkish Minister of Culture and Tourism. It would seem that the Turkish government wants to make their standpoint on the Armenian question clear to all foreign tourists, (the majority of which certainly didn’t even know that there was an ‘Armenian question’). In Germany, we have a saying for this: ‘Getroffene Hunde bellen’ (or, roughly, ‘methinks thou doth protest too much!’).

Anyway, we finished off our evening peacefully on our balcony at the Hotel Erguvan. Between us was an emptying bottle of wine from the host’s vineyard. His wife had brought it to us as a kind gift on a pretty tray, along with a few nuts. The sun sank, the swifts retreated, the mosquitos arrived, and we decided that we’d had enough for the day.

The next instalment of our numismatic diary deals with a city that every person on the globe probably knows and has already visited at least once – at least judging by the hordes of tourists who hang around there. We continue on to Ephesus.

All parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ can be found here.