by Ursula Kampmann

July 18, 2013 – It was the last night in Pamukkale. We were sitting in our hotel room, packing, when the phone rang. We were startled, but turns out there was no reason to be. It was Mr. Rasit Özkardes, the kind owner of the Toyota repair shop in Denizli who had personally driven us back to Pamukkale. I had such a guilty conscience, since his shop wouldn’t be getting any business from us. He had gone to all that trouble for nothing. But all Mr. Özkardes wanted to tell us was that our car had now been picked up, and asked if there was anything else he could do for us. On top of that, he told us that if we ever made it back to Denizli, he’d be honoured to have us as his guests.

I felt more than a little ashamed as I thought about how a foreigner would be treated back home if their car had broken down, then ended up in a repair shop that had put in a lot of work and not gotten anything out of it in the end.

Sunday May 5, 2013

We had booked a taxi to bring us and our seven items to Izmir. As a final treat, we had allowed ourselves to indulge our hankerings for home – we stayed at the Mövenpick Hotel Izmir. The only thing that definitely wasn’t Swiss here though was the prices, which for a five-star hotel were really quite affordable.

Bridal fashions alla Turca. Photo: KW.

I was very excited that we’d be getting to Izmir again, since there was a museum newly opened in 2004 that I’d really liked to have seen – the Izmir History & Art Museum. The Dumont Travel Guide Turkey – Western Turkey / Central Anatolia has this to say about it on pg. 217: ‘The Izmir History & Art Museum was opened in 2004 in the old Italian exhibition pavilions as the second new museum, and it shows the history and art of the city in a contemporary context. Many exhibits from the Archaeological Museum are now displayed here, such as the recumbent river god Kaystros with cornucopia, from Ephesus, and the reliefs of the Battle of the Centaurs from the Belevi Mausoleum. Other showpieces include magnificent sarcophagi, as well as the bronze figure of a running Ephebe. A secondary pavilion features ancient and medieval coins, all the way back to the very first money of the Lydians from the 5th century BC.’ Well, I suppose you can’t really expect a tourist guide to have actually looked up when the first coins were minted, but otherwise it sounded really promising! The old Archaeological Museum of Izmir had already been something special, and now its greatest treasures were brought together in a modern presentation. We set off to find it right after our arrival.

Finding the museum, however, proved to be not so simple. We had come up with the clever idea of following the signs to the tourist information centre, so we could inquire whether the museum was even open. The museum was indeed open. But the tourist information centre was closed. But when does a minor detail like that ever stop anyone in Turkey from offering up some friendly information? We interrupted a relaxed Sunday gathering of no less than 10 men. Immediately they located someone who unlocked the cabinets to get us the brochures, another one spoke German, and in no time we were on the right track.

It led us along a long street with one bridal shop after another. We passed a simit seller, who – times have changed – not only had the delicious sesame pastry, but also all sorts of sandwiches and börek. We finally found the park and asked the way to the (admittedly somewhat shabby) pavilion. And there we were, rife with curiosity for the magnificent antiquities.

A particularly accomplished inscription. Photo: KW.

Let’s put it this way – we were speechless. There were great objects there, no question, but in those grubby surroundings, even the Archaic and Hellenistic masterpieces looked like second-rate fakes. Then there were the very unique, arbitrary labels. For example, we came upon a larger-than-life stele covered with letters. Surely this would have particularly thrilling historical or culturally historical origins. A small label promised some ‘clarity’: Inscription / Clarus. Well … there you go.

Classical Homer. Photo: KW.

Right at the entrance, you’re greeted by the slightly larger-than-life statue of a seated man. ‘Seated man (Homer)’ said the description. ‘Classical Period,’ ‘4th century BC.’ So which one is it? Classical, or from the 4th century?

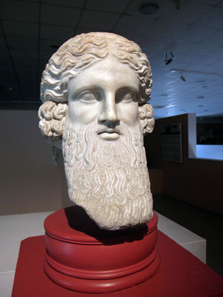

Head of Hermes, dated 30 BC to 395 AD. Photo: KW.

Particularly popular for dating purposes was the term ‘Roman Period,’ whatever that was supposed to mean. A single sign was to offer information on this burning question, providing an explanation for this magnificent archaistic head. Dated: Roman Period / 30 BC – 395 AD. Okay.

Statue of the river god Kaistros. Photo: KW.

There were also some magnificent objects, of course, like the statue of the river god Kaistros.

Relief on the floor. Photo: KW.

What was irritating here was the complete lack of effort on display throughout the museum. There was a fascinating relief depicting a leg of meat being cut up and dishes being washed. Has anyone ever seen an ancient depiction of this kind of everyday occurrence? As I said, fascinating. Unfortunately, you had to lie on your stomach to really appreciate the almost 40 cm high relief. Because it was standing on the ground. Actually hanging it up and giving it a label had probably been too much work.

The coin exhibit. Photo: KW.

Things really started to get bad once we got to the coins …

No, not a single one of these pieces was on display. Photo: KW.

A board featuring magnificent pieces lured us to the dismal display cases. The pictures were extremely familiar to me. And no wonder, since all these coins can be found in the great cabinets of the world – something that was not indicated by a single one of the picture references. It was assumed, apparently, that the experienced viewer would themself realize that the pieces here had been stolen mainly from the Franke-Hirmer. The pieces came from Frankfurt (Phanes stater), Munich (electrum stater with lion and calf) and London (the rest), which is certainly not interesting to the layman (it has to do with copyright and propriety; somewhat irrelevant in the internet age). So yes … perhaps the Turkish individuals responsible were trying to offer a subtle hint that all the good pieces are to be found abroad, while they are only able to display third-rate ones.

Wherever you looked: electrotypes. Photo: KW.

Which they also didn’t even do. When viewed from an angle, you could see that they were actually electrotypes, once again described with their own very particular terminology. It’s unlikely that any expert would have described the hektes from Mytilene and Phocaea as western Anatolian coins.

You have to wonder why this museum was assembled so carelessly. Did they not have enough time? Not enough money? No experts? There’s certainly no shortage of fantastic Turkish archaeologists and historians! It’s too bad none of them were involved.

Anyway, we left, enraged. We were angry on behalf of all the truly amazing objects in this museum to which absolutely no respect is shown.

Monday May 6, 2013

We got up at an ungodly hour, as we had to have that stamp wiped out of my passport that we were given upon entering Turkey. It stated that I had to be with the car upon exiting the country as well. According to the ADAC, we were to export the car at Turkish customs, leave it in the free warehouse, where the ADAC would then, within a reasonable time, pick it up with all the necessary papers and bring it to Germany.

Customs office, Izmir. Photo: KW.

When we arrived at the customs building at 8:00 am, the Özen company tow truck was already there with our little Toyota. Mr. Ögret, who speaks excellent Turkish, had brought along a companion whose mother spoke German. The plan was to communicate any uncertainties or confusion via the daughter to the German-speaking mother, and then arrive at a solution. Even the ADAC had offered up their translation services. Mr. Özen also had a bundle of papers with him, with every Turkish form precisely translated into German. I can tell you one thing – it’s only in times like these that you realize just how much you can do and negotiate with just your hands, feet, and maybe two or three Turkish words (tamam, yavas, evet).

Mr. Özen battling Turkish bureaucracy. Photo: KW.

But nevertheless, let me put it this way: without the ADAC, we wouldn’t have had even the slightest chance of ever getting our car (and me, especially) out of Turkey. To us, the procedure was convoluted, unpredictable, and extremely complicated. There was an open plan office with various workstations, and while some of the officials busied themselves with papers, the oldest one was completely engrossed in reading his newspaper. When a paper was pushed towards him, he briefly interrupted his reading to take a stamp out of the drawer and press it against the paper.

You can’t see it here, but this woman was, in all seriousness, painting her nails at work. Photo: KW.

A woman who seemed to think quite highly of herself was chatting with the person opposite while leisurely painting her nails. Up until now, I’d thought that kind of thing only happened as the cliché of a secretary in American crime fiction dramas! But no, here it was happening for real. All I could do was stare. The busiest person there seemed to be an older woman, who was constantly darting back and forth between the officials to give them tea and coffee.

As I said, it took some getting used to. Twice, a very nice German man of Turkish descent translated for us. And, of course, he also told us his story. This was already his fifth or sixth time here at the customs office. He also had to have the stamp removed from his passport. He had made the mistake of lending his car to a relative, who then very promptly proceeded to cause an accident in it. The owner, not the relative, was the one being held responsible, because he never should have given the car to him in the first place. Although no one had been injured, the accident was a bad one, and he’d had to scrap the car. The whole thing had already cost him several thousand Euros. Unfortunately, it was still practically impossible to get all the necessary papers to get the stamp wiped from his passport. And I heard him swear to high heaven that he never would leave his beloved, orderly German homeland again for travelling in this country of despotism.

The engine damage is assessed according to customs formalities. Photo: KW.

After about half an hour, a customs official in an elegant grey suit and crisp white shirt accompanied us to our car, probably to check if we were trying to smuggle anything illegal in it. The inspection was to his satisfaction, and within barely another hour we had the three stamps that we needed to deposit the car in the free warehouse.

Waiting in the free warehouse. Photo: KW.

We cruised around Izmir for a while until we found the entrance to the free warehouse. It was thrilling. There were containers piled everywhere. Huge trucks constantly wanted to get by where we were standing. There were cars waiting in a confined area, some clearly having been there for years. And I became increasingly uneasy … Would I ever see my little car again? I spoke to the car in reassuring tones, explaining that the good people at ADAC would never leave him here alone!

A car remains behind. Photo: KW.

After about another hour and a half, someone came along to open the large gate for us. He pointed out the place where we were to leave the car, and with that, everything was taken care of – or so I thought! In actual fact, there was still one more station to go. This required a notary, who would officially confirm that I would hereby designate the ADAC to bring my car back to Germany and that the ADAC representative was authorized to take care of all necessary export formalities at customs.

And so off we went to a notary. It was about half past eleven. We found ourselves in a small office that you can imagine as a sort of currency exchange office with a high counter. Only there was a small waiting area with seating and a glass-separated area for the notary. It was pandemonium there. There were about a dozen people waiting at each counter. By the time we’d fought our way to the front, we were kindly told that the notary was already on his lunch break. We’d be able to see him again after 2:00.

The notary isn’t taking people. He has computer problems. Photo: KW.

We also went for lunch, and came back at 2:00 pm. And then we waited yet another two hours. For what exactly? Not a clue. In the meantime, the notary was sitting in his little cubbyhole and obviously having computer problems. At some point, a young woman came over and introduced herself as an interpreter. She would have to translate the text to me (the ADAC translation of which already existed, of course). She did so, took the money, and with that the formalities were over and done with. We had – oh wonder of wonders!!! – managed to satisfy all the demands of Turkish customs within less than a day. Visibly relieved, our guardian left us in the direction of Denizli. And we called the ADAC to let them know that everything was now done. Great, came the voice on the other end, now we’ll book your flight home. We wouldn’t even have to pay anything for it. When did we want to fly? After yesterday and today, we’d had enough, so ideally the next day!!!

In fact, a quarter of an hour later, we were informed that we’d be flying from Izmir to Basel on Tuesday afternoon. And the costs of the excess luggage, we were told, would also be covered by the ADAC.

Konak Square. Photo: KW.

And just like that, what was intended to be a long vacation was suddenly reduced to just a few more hours. We weren’t just going to sit around the hotel though. We got a taxi to Konak Square, where we proceeded to lose ourselves in the alleys of the bazaar.

Smyrna. Tetradrachm, 2nd century BC. Gorny & Mosch 211 (2013), 376.

Smyrna is one of the oldest settlement areas of the Mediterranean basin. Even Herodotus tells extensively of the city, which was destroyed around 545, prior to the Ionian Revolt. The favourite founding myth of the city refers back to Alexander the Great, who ordered the reconstruction of the new Smyrna around 340 BC. The city quickly became wealthy through trade. So rich, in fact, that its local politicians competed with Ephesus and Pergamum to be allowed to be the first to allow representations at the assemblies of the Koinon of Asia.

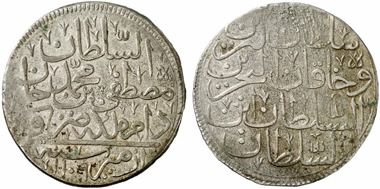

Ottomans. Zolota 1106 (= 1695), minted in Izmir. Künker 210 (2012), 953.

From the 11th century on, the ruling parties changed: Saljuqs, Byzantines, Knights, Genoese, then the Turks again, then the Christians again, and we can’t forget the Mongolians … Let’s leave that be, though, and jump right to the year 1426, when the Ottomans took over the government. Smyrna developed into a lively trade city where many Jewish merchants had also settled after being expelled from Spain.

The city’s heyday began in the 17th century, when the Ottoman Porte granted particularly favourable trade conditions to foreign merchants. By 1700, the city had grown to 90,000 residents. In the 19th century, the first Turkish railway ended here, which brought cotton and other agricultural products from the fertile valleys to the city. Smyrna was, at the time, a cosmopolitan metropolis.

Greek refugees mourn the victims of the Catastrophe of Smyrna. Source: Wikipedia.

According to the official 1910 Ottoman statistics, 974,225 Turks, 629,002 Greeks, 17,247 Armenians and 24,361 Jews lived in Smyrna, alongside 58,076 members of other nations. Then came the First World War, which ushered in the demise of the Ottoman Empire. The Catastrophe of Smyrna actually began with the Treaty of Sèvres, in which the victorious powers made sure that Greece got huge expansions of territory. It obtained western Thrace, although without Edirne. Thessaloniki, today the second largest city in Greece, has only been part of Greece since this time. There was also the potential opportunity to acquire additional territories in the foreseeable future. For the time being, however, they were to remain Turkish property under international law. The Greeks were only permitted to govern. Following a transitional period of five years, there was to be a referendum (similar to the situation in the Germany-France contested Saarland), which would further clarify the affiliation of the territories.

Mustafa Kemal, better known as Atatürk, did not acknowledge this treaty. Soon, partisans were battling against the Greek troops. Civilians, in particular, suffered the consequences, on both sides. Punitive expeditions intensified the hostility that had grown between the two ethnic groups during the First World War.

The conflicts escalated into a campaign of the Greek army against the Turkish forces, which were led by Mustafa Kemal. There were several bloody battles, which culminated on August 30, 1922 in the victory of Dumlupinar, which is still celebrated today in Turkey as ‘Day of Victory.’

What followed is known to the Greeks as the ‘Asia Minor Catastrophe.’ On September 9, 1922, the Turkish army conquered Smyrna. In the first days after the victory, a reported 40,000 people were killed. A fire that had broken out for unknown reasons in the Armenian quarter claimed some of the victims. Any surviving Greeks were expelled or fled. This, of course, had dire consequence in the areas that had until recently been Turkish and were now under Greek rule. Here, too, people were expelled – all of those who professed to Islam.

Tens of thousands of people – Greeks and Turks – died while on the run. In the Treaty of Lausanne, the victorious powers attempted to mediate, so that an orderly exchange of the population could be carried out. As if there could have been any semblance of order with such a thing! In any case, the treaty robbed 1.25 million Greeks and 500,000 Turks of their homeland.

Agora of Smyrna. Photo: KW.

I have to admit, it’s easier to work with ancient history. You don’t run the risk of expending too much emotion, since all the victims of the great massacres are long since dead and none of the members continue to suffer the repercussions.

And so, let’s turn our attention once again to antiquity. Through the bazaar, we came to the Hellenistic Agora of Izmir. It was already 4:30, and so the excavation was only open for another few minutes. I still looked at everything intently, though.

Underground vaults. Photo: KW.

The underground vaults are particularly impressive, and once housed large market halls. I wandered through the wide passageways all on my own.

A tidied up Ottoman cemetery. Photo: KW.

What I liked even better, perhaps, was a tidied up Ottoman cemetery, which clearly calls to mind the Swiss artist Ursus Wehrli.

If you’ve never heard of Ursus Wehrli, by all means, click here.

Spices – the epitome of a bazaar. Photo: KW.

Right. And with that, our holiday in Turkey had almost come to an end. We wandered a bit more through the bazaar, bought a souvenir or two (no, nothing too heavy) …

They didn’t just have tea, but also the best coffee in all of Turkey. Photo: KW.

… and ended our trip and the day in an open courtyard, where Kurt enjoyed the best coffee in the world at Halis Dibek Kahve.

On Tuesday May 7th, we flew back to Basel. Our car didn’t arrive until a week later. On June 3rd, it was back in Lörrach – or, more precisely, in the Toyota repair shop in Weil, where the injectors were fitted, which, incidentally, were not the cause of our breakdown. Over the next 3.5 weeks, the entire machine was replaced. The cost to me was ‘only’ 3,000 Euro, the rest of the expenses were covered by Toyota Germany and the Toyota repair shop, since it’s absolutely abnormal for a 4.5-year-old car with a mere 80,000 km on it to have the motor die. At any rate, we had certainly made the right decision back in Denizli.

I’m happy to report that as of June 28th, my car and I have once again been happily on the road. So you can look forward to more travelogues 😉

You can find all parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ here.