by Ursula Kampmann

Monday, April 15, 2013

And we’re off! After endless weeks of waiting and preparation, we set off to the south. Even though we have almost six weeks to explore Turkey, we’re obviously eager to enjoy the journey there and back as well. And so, it’s off through the Brenner Pass headed towards Bolzano in South Tyrol. There’s hardly anyone on the roads. In fact, on this gloriously bright Monday, it feels like everyone else is stuck sitting in their offices while we get the Brenner Pass all to ourselves. There’s still snow on the mountains. If only there were a particularly good place to pull over, a little snowball fight might have been in the cards! But with no place to do so, we made it to Bolzano in record time.

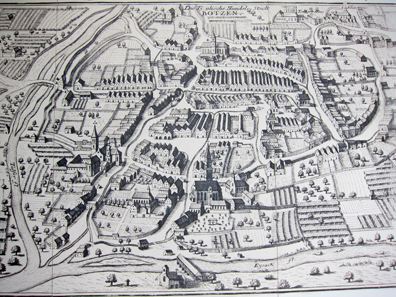

Bolzano city plan. By Gabriel Bodenehr from 1710/20. Photo: KW.

Although there was already a small settlement here in the Middle Ages, Bolzano is truly a child of the flourishing trade of the High Middle Ages. Around 1170/80, the Bishops of Trent, who controlled the region, founded a very manageable settlement here that was to become one of the major trade centres. The endless convoys of trucks making their way across the Brenner Pass alone give you a hint of just how important this trade city still is today. Bolzano was a hub between Venice and Augsburg, so, between the Italian trade cities and southern Germany. The Bolzano markets became a regular, fixed occurrence. The most important trade cities would send their agents who would then spend 14 days processing their purchases and sales while being protected by a special law.

Tyrol. Leopold IV, 1396-1406. Meran twenties. From Rauch 73 (2004), 1550.

Much of the trading was done in wine – even in the Carolingian era, the Bolzano vines were famous! But there were also animal hides and leather, cloth, linen, cotton, silk, spices, grains, olive oil, wax and horses on offer.

It was quite possible to grow wealthy doing this, particularly because the foreigners conducted their business dealings through a local broker. The Bolzano arcades, boasting houses up to 70 metres deep, still attest to the city’s prosperity.

Walther von der Vogelweide. Photo: KW.

The heart of the city is the central Walter Square. It’s a place where you can sit in various street cafes and simply watch life go by and ponder the ways of the world. But Walter Square didn’t, in fact, start off as Walter Square. It was originally called Maximiliansplatz after the Bavarian King Maximilian II who had it laid out. Then, the reign of the House of Wittelsbach came to an end. The Habsburgs returned, and the square was renamed: Johannisplatz, after the Archduke Johann. As you know, Habsburg rule also didn’t last forever. In 1918, Italy conquered South Tyrol and again renamed the square. After whom? Surprise! Vittorio Emanuele III. And once history was done with him as well, it was decided that the square would have the seemingly innocuous name ‘Walter Square.’

But careful: anyone who knows the backstory to this knows better than to refer to it as a politically correct landmark. The Walther monument was created in the last third of the 19th century as a profession of Bolzano’s belief in German culture. At the time, academics maintained that the great German poet Walther von der Vogelweide came from South Tyrol. The monument was erected in Johannisplatz and was clearly intended in a German-national sense. In any case, this is how the neighbouring land understood it – Italian-culture avowed Trent in turn immediately erected a Dante. When South Tyrol came under Italian rule, Walther had to be moved. A small park was found as the new location. In 1981, Walther was returned, and today he looks on happily as guests in the cafes in his square effortlessly switch back and forth between German and Italian.

Bolzano Franciscan Church: Portrait gallery of famous Doctors of the Church. Photo: KW.

It goes without saying that there’s a lot to see in Bolzano, especially with regards to economic history. But we wanted to save that for the next day. After all, we were going to be guided by ‘the’ economic historian, Professor Dr. Dr. Helmut Rizzolli. And so, today, we just visited a few more churches and happened on some exciting finds, like a portrait gallery of important Doctors of the Church. The unique fresco was painted around the year 1500. It’s the dream of every academic. Finally, for once, the focus is on the theorists!

Professor Dr. Dr. Helmut Rizzolli and Ursula Kampmann. Photo: KW.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

We were set to meet Prof. Rizzolli at 10:00. The enthusiastic Bolzano native is by all accounts an academic, but certainly not a hard-core theorist. Quite the contrary! Although he’s the author of arguably the most important books on Tyrolean economic history, perhaps even more important is his political-cultural involvement. He served on local council for years, and in this function saw to the restoration and reopening of, among others, Runkelstein Castle. What’s more, Mr. Rizzolli comes from an old Bolzano merchant family that still runs its family business in the arcades. Could we have hoped for a more competent guide through Bolzano and Runkelstein Castle?

Runkelstein Castle from the outside. Photo: KW.

So, just to head off any possible misinformation straight away – over the next few hours, we were completely bombarded by information. And I’m not entirely certain that I’ve remembered everything correctly. So let me say right off the bat that any mistakes that may eventually come to light are entirely my doing and can be blamed on my aging, failing memory!

The oldest parts of the castle date back to the early 13th century and were built by followers of the Prince-Bishop of Trent. The castle was used to monitor the trade route to the north. When the bishop fought the up-and-coming Count Meinhard II of Tyrol for influence in the Bolzano region, the count besieged and conquered the castle and, in the years that followed, entrusted it to several of his followers.

The Vintler coat of arms with the two white bear paws. Photo: KW.

Franz and Niklaus Vintler, rich merchant brothers from Bolzano, were instrumental in the features and decor of Runkelstein. They owed their rank mainly to their lavish means – Leopold III relied not only on their advice, but, above all, on their money. As thanks, the Vintlers acquired Runkelstein castle in 1385, a move that elevated their status, even if in reality they couldn’t keep up with their peers. With their generous budget, however, the brothers made the hereditary nobility look foolish and out-dated. They decorated Runkelstein castle so opulently that even today the Bolzano Tourist Bureau raves of the legendary ‘picture castle’ that easily scores points with the largest fresco cycle of the Middle Ages.

Construction of the castle; a crane can be seen clearly on the upper left edge. Photo: KW.

And the abundance of images really is something. Here, for example, we have a depiction of the castle itself, an image that can be dated fairly accurately since the summerhouse, the third large building complex that was started in 1390, isn’t yet present.

The public baths – an original room from the Middle Ages. Photo: UK.

Runkelstein Castle really gives you an idea of what a castle looked like in the 14th century. Here, Professor Rizzolli is explaining to Kurt Wyprächtiger the so-called bathhouse, a place where no bathing ever actually took place. The name is due to a misinterpretation of some of the frescoes, which are perfectly preserved in the original, as are the floors and ceiling.

Contemporary invoice. Photo: KW.

I have yet to figure out what exactly an original bill sitting on the inside of one of the window frames is supposed to reveal about this period …

Depiction of a jousting tournament, around 1395. Photo: KW.

For the most part, people just don’t give enough thought to things – like, for example, how much these grand jousting tournaments, where knightly show-offs flaunted their importance, must have cost. And who might have financed the knight’s armour and the tournament?

A section from the depiction of the jousting. Photo: KW.

Upon closer inspection of the image, you get a clue. On the edge of the fresco, some Jewish people are depicted watching the tournament. Leopold III and his economists, the Vintlers, worked together perfectly with Jewish bankers. And this representation is likely owing to the fact that they provided the financial means for the tournament.

And another tournament: The club tournament. Photo: KW.

Incidentally, the noble knights didn’t just fight with lances. They also fought with clubs – even if they were known at the time by the more genteel name of ‘maces.’ In one particular form of the tournament, the aim was to use the club to knock the crest of the opponent’s helmet from his head, or better yet, knock the opponent right off his horse. Because there were always severe injuries associated with this kind of tournament, the church tried to ban them.

Female spectators on a mobile grandstand. Photo: KW.

The noble ladies did not avert their eyes under such circumstances, of course. Quite the contrary: The fresco depicts how the damsels were moved on a mobile platform right into the heart of the action. It was the women, of course, who awarded the decisive points for knightliness.

And if you’d like to see just how such a tournament worked, have a look at the pictures from our visit to St. Wendel where we attended a reproduction of a jousting tournament from the time of Maximilian I.

And here, something that will make the Germanists swoon: Scenes from the story of Tristan and Iseult, written in 1210 by Gottfried von Straßburg. Photo: KW.

Germanists literally rave about the images in the summerhouse. The frescoes in the Tristan room tell the oh-so-romantic story of Tristan and Iseult. Clearly seen in this picture are: Tristan’s journey to Ireland to court Iseult for King Mark; as well as him fighting a dragon, whose tongue Tristan cut out as a symbol of his victory, clearly visible in our picture.

It’s pure luck, incidentally, that these frescoes are still so fully preserved. In 1868, part of the north wall collapsed, dragging the frescoes under with it. But they managed to remove the paintings and apply them to the newly built north wall (if I’m remembering correctly, not necessarily in the correct order, but still!).

The Knights of the Round Table of King Arthur. Photo: KW.

Our rather Anglophile generation, though, can relate much more to King Arthur and his Round Table. It’s depicted in the Garel room. Garel found recognition as a knight in the service of King Arthur because he fulfilled the knightly canons of virtue perfectly. One can only imagine the pictorial slap in the face this depiction by a merchant family must have been to all the old-established nobles attending one of Runkelstein Castle’s many lavish celebrations. Here was a nouveau-riche family holding up all these smug, arrogant knights against a depiction of how they were actually supposed to behave!

Coat of arms, affixed by Emperor Maximilian I. Photo: KW.

The Vintler brothers certainly didn’t make any friends this way. And when Leopold III was killed in the Battle of Sempach, there were dire consequences – for the country and for the Vintlers. Leopold’s successors knew nothing about financial policy. Out of religious considerations, they renounced Jewish capital. The fact that Duke Frederick is written large in history as he ‘of empty pockets’ is connected to this economic misstep.

Leopold’s death spelled the end of the Vintlers’ financial backing. His heirs did not repay their debts, and Niklaus Vintler died in 1413, destitute. In the second half of the 15th century, his successors had to sell Runkelstein Castle to Sigismund the Wealthy. He then bequeathed it to Maximilian I, who had it renovated and partially reappointed. The coat of arms on this contemporary fireplace was added by Maximilian I.

Interior courtyard of Runkelstein Castle. Photo: KW.

And those were just a few highlights from the amazing abundance of images. But for anyone who thinks that those alone count as having seen Bolzano’s main attraction … well, we will gladly show you the error of your ways! For economic history aficionados, there’s actually something much more incredible down in town, somewhat hidden and not completely overloaded with tourists: A testimony of how long-distance traders handled their disputes on the spot prior to the introduction of international trade law.

Entrance to the Bolzano Mercantile Court. Photo: KW.

I mean, you have to imagine this in a practical sense. Here were traders coming together from all corners of the world, possibly not speaking each other’s languages well enough, one of them perhaps even aiming for fraud, and there you have a law suit on your hands. Anyone who’s familiar with the courts of the Early Modern Era knows just how long something like that might have dragged on. By the time a judge was even available, the trade fair would have been long over and the merchant would have been off to his next business meeting.

A look at the baroque courtroom. Photo: KW.

In order to get this problem under control, from the 17th century on Bolzano had its own tribunal to which lawyers had no access, so as to shorten the litigations …

Case law was handled by the traders themselves, and in Italian as well, since the Germans were well versed in it, but the Italians didn’t understand German.

The bench with its three seats. Photo: KW.

The judges would alternate between a German and an Italian. The two assessors had to belong to the opposite language community of the judge in order to reach a balanced verdict.

It’s a bad shot to be sure, but it’s of a unique image: the depiction of an exchange. Photo: KW.

After the trade fair, the merchants would gather in the exchange room to settle their debits and credits. Bolzano bought this image in 1701 for 70 gulden, and it depicts the function of the exchange. To the right is Mercury and in front of him is a small angel who is holding up an empty wallet and also holding a paper in its hand. Another angel similarly carries a whole stack of bills to Cronus, in order to get his money back.

An exhibition on Bolzano economic history. Photo: KW.

In addition to these unique places, the Mercantile Museum also has an instructional exhibition on Bolzano economic history. And, of course, there’s also a coin display.

Bolzano. Prize medal of the Jubilee exhibition 1898, dedicated by the Trade and Industry Chamber in Bolzano. From Rauch 85 (2009), 2299.

Even today, the Bolzano Chamber of Commerce still has its own coat of arms that hints at its former significance: A globe on a column, around which lie bales of fabric.

The Falliden little bell. Photo: KW.

The people of Bolzano obviously weren’t yet familiar with Triple A, but they had their own way of dealing with companies that tried to protract their insolvency. In the courtyard of the Mercantile Court was a small bell, which was rung when one of the firms participating in the trade fair was no longer able to pay.

The Bolzano Municipal Museum – featuring a collection worthy of a national museum. Photo: KW.

No, we didn’t see the Ötzi museum. Instead, we stopped into the opposite facing Bolzano Municipal Museum with its unique collection of Tyrolean art and handicrafts. Our guide there was Dr. Stefan Demetz, a student colleague from ages ago and a good friend. He laments that since 2003, the state museum has only been able to display a portion of its collection. Everything was actually supposed to be rebuilt, but so far, that hasn’t happened. The economic crisis intervened. As such, the important collection of Tyrolean coins and medals is currently sitting in the archive and cannot be viewed. All the same, a small portion of the inventory is on display in six halls, and this alone is worth seeing.

View from the Municipal Museum. Photo: KW.

Especially when it’s such a glorious day. Then you can take the elevator to the museum’s top floor and enjoy a spectacular view of Bolzano.

In the evening I attended a lecture by Professor Rizzolli on the topic of monetary unions. Naturally, the subject of the current Euro crisis came up, and it once again became clear just how differently the national medias report on Europe’s economic situation – and, therefore, how divergent the opinions are. One attendee asked, for example, why the Germans are complaining about how much they now have to pay. Ultimately, as suppliers, they would have made the big money during the times of the surplus. I can’t remember ever having read this quite serious argument in any German tabloid paper.

And that was it for Bolzano. One thing is certain – There is so much numismatic and economic history here that it definitely won’t be my last visit. And after all, the old mint of the County of Tyrol, Meran, is still awaiting my arrival!

But the ferry was waiting. Join us for the next leg of our journey as we cross Greece, ferry across the Dardanelles, and look for the ruins in Cyzicus …

All parts of the series ‘Springtime in Turkey’ can be found here.