by Ursula Kampmann

April 12, 2018 – It is a tempting idea: you gain and bind coin collectors by regularly supplying them with commemorative coins at face value. Not only do these look beautiful, but they are also of stable value due to the silver content in the alloy and thus in high demand with large sections of the population. With these coins a profit can be made, for many buyers do not feed the coins into the cash cycle, but hoard them instead. And this is precisely why the nice marketing trick has its downsides.

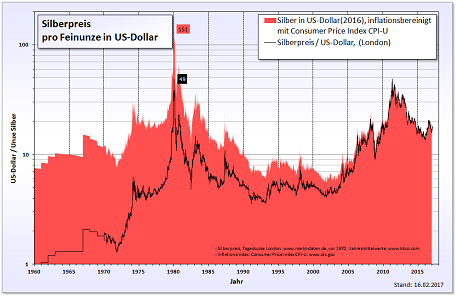

The changing silver price in us-dollars. Source: Realterm / Wikipedia. BY-CC 3.0.

A matter of fact: the silver price is subject to fluctuations

Strictly speaking, we all know it: sometimes the price of silver is subject to enormous fluctuations. But there is a minor side effect that does not immediately catch the eye: the price of the precious metals silver and gold is directly related to the demand for coins – whether it is pre-1945 rarities or contemporary coin issues.

As a matter of fact, it is quite simple: once investors lose confidence in economic prosperity, in other words as soon as share prices fall and the stability of our currencies is doubted, larger circles of people invest their money in investment products – or in what they consider to be investment products. For this reason, the demand for commemorative coins with silver content is particularly high once the silver price is high, too. Conversely, there is a risk that large quantities of these coins will be put into circulation (or returned to the Mint / National Bank) precisely when the silver exchange rate is in freefall.

It is therefore of the utmost importance to choose the face value of such coins in such a way that there is no risk of excessive losses even if the silver price is plummeting.

Austrian circulating commemorative coin of 1979 featuring a face value of 100 schillings.

A textbook case of the silver danger: the “Austria” case

The example of the Austrian 500-schilling commemorative coins, which were minted and sold in the 1980s, is almost a lesson of how dangerous the lightly issue of commemorative coins can be when silver prices are exploding.

You certainly remember: this numismatic episode happened against the background of the great silver speculations of the Hunt brothers. These two speculators, whose family is said to have served as a model for the then rather popular US-American TV series “Dallas”, believed to be able to control the silver market. They drove the price of an ounce of silver from $6.70 (February 1974) to $52.50 (18 January 18 1980) before the price of silver ended by a mere $5.00 again in June 1982.

The problem with these speculations was the fact that a Ministry of Finance and its Mint – in this case the Austrian Ministry of Finance and the Österreichisches Hauptmünzamt (Imperial Austrian Mint) – were of course unable to react to the dramatic changes in the market quickly enough.

As had been customary for years, the Austrian Ministry of Finance released four issues of 100-schilling commemorative coins in 1979, with a total face value amounting to 8.335 million schillings. The coins sold right away, for the silver price was rising at the time. On 18 January 1980, the intrinsic value of a 100-schilling piece was nearly 25 dollars. This was roughly three times its face value and, of course, made the Ministry of Finance’s revise its policy of issuing coins.

Austrian circulating commemorative coin of 1980 featuring a face value of 500 schillings.

The Ministry then raised the face value to 500 schillings. But even before the first 500-schilling circulating commemorative coin was issued, the silver bubble burst and the silver price fell. On the day of its issue, the first issued 500 schillings coin only had a good 7 dollars of intrinsic value left which was roughly one-fifth of its face value.

Additionally, as a consequence of the fall of the silver price – see above – interest in coin collecting declined. The coins issued did not find enough buyers, and the mintages could not be lowered at the same pace interest was dwindling. While the second circulating commemorative coin of 1980 still had a mintage of one million specimens, it fell to 750,000 with the third issue and ended with 500,000 coins the same year. Even the rise in silver fineness two years later did not bring the customers’ interest back.

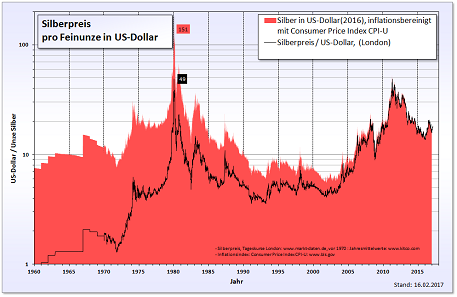

Circulating commemorative coins are also part of the money supply in circulation, which can quickly add up, mainly because hardly anything flows back to the National Bank. The face value of the issued schillings is highlighted in blue, and the accumulated face value in orange.

The danger of “sleeping” coins

The Austrian Ministry of Finance could call itself quite lucky, however. From an economic point of view, 1980 was not a bad year. The citizens of the country saw no need to reintroduce their “sleeping” circulating commemorative coins into the cash cycle. The Ministry of Finance thus limited its measures to adjusting the mintage and did not take any further steps.

This was a problem, because the coins of course remained fit for circulation and gradually added up to a large part of the cash potentially available. At the end of 1987 around 98 billion schillings worth of bank notes in circulation were facing 25 billion worth of coin circulation in Austria, of which the hoarded circulating commemorative coins constituted more than 18 billion.

The Oesterreichische Nationalbank found a way out of this dangerous situation: it bought the minting privilege as well as the mint from the Austrian state. Both were converted into a public limited company with registered shares, the Münze Österreich AG (Austrian Mint AG), and sold to the Oesterreichische Nationalbank for 8 billion schillings. Even after the sale, the Austrian Ministry of Finance remained responsible for financially compensating when the commemorative coins issued before 1989 were returned.

Through a cautious increase in the nominal circulation of money by issuing bullion coins, the OeNB, in cooperation with the Austrian Mint, managed relatively quickly to reduce the dangerously high proportion of commemorative coins in the theoretical cash cycle to a bearable percentage. Over several decades this mountain of circulating commemorative coins was reduced in an economically viable manner.

The 2011 German circulating commemorative coin “125 Years of the Automobile” without silver – a real slow-seller. Photo: Stphn / BY-CC 4.0.

A new silver boom and three ways to react: Germany, Switzerland and Austria

An isolated event? No, of course not. The silver price is rising and falling. Again in the first half of 2011, the silver price increased so considerably that in many places consideration was given to finding a reasonable ratio between the face value and the intrinsic value of the circulating commemorative coins with silver content to be issued.

At that time, Germany decided not to raise the face value, but produce two versions of the circulating commemorative coins: a collector’s version in silver, which could be bought at the Official Sales Agency of Collector’s Coins of the Federal Republic of Germany for an additional charge that could be altered at any time, and a circulating commemorative coin without silver, which banks continued to sell at face value.

The result was a decline in the population’s interest in circulating commemorative coins. The mintage dropped from nearly 1.8 million (2011) to 1.5 million (2012), 1.3 million (2013), 1.2 million (2014), and 1.1 million (2015). In April 2015 the German Ministry of Finance decided to reverse its decision and resume issuing circulating commemorative coins that were made of silver. At the same time, however, the face value of the coins was raised to 20 euros.

Switzerland chose a different path. Since 2011 all circulating commemorative coins – whether in Uncirculated or Proof quality – have been sold via Swissmint for an additional charge. At first, the selling price was raised to 30 francs, but after the fall of the silver price at the beginning of 2012 it was lowered to 25 francs, to be raised again to 30 francs early in 2017. However, this measure does not seem to have done the sale of coins any good, either. The mintage was reduced from 50,000 specimens in 2015 to 35,000 specimens.

The 2011 Austrian copper coin was a complete success. Photo: Austrian Mint.

The Austrian Mint went a completely different way, although it is important to mention that it only issues a minimum of circulating commemorative coins. When the silver price rose, the Mint stopped immediately issuing silver circulating commemorative coins at face value, in order to gain some time to come up with a new concept. On 14 December 2011 the time had come. A new circulating commemorative coin was released, albeit not made of silver but copper.

To date, it has become an extremely popular collector’s item and is often bought and given away as a present also by non-collectors. The marketing department of the Austrian Mint had hit on the ingenious idea of establishing it as an ideal gift, accompanied by an appealing packaging, on the occasion of visits between Christmas and New Year’s Eve. With 300,000 specimens, the mintage is about twice of what used to be minted of the silver versions in circulation quality.

The Canadian version

The Royal Canadian Mint took a completely different approach in reaction to the silver boom. It used the suddenly emerging silver hype to launch its Face Value Program in 2011.

In spite of its great name, this Face Value Program is basically nothing else than the silver circulating commemorative coins with silver content that are issued in Europe. There is one crucial difference, however: while the European models are indeed legal tender backed by the State, the Canadian coins have been defined as non-circulating legal tender. In other words, neither the trade nor the banks are legally bound to accept the specimens as payment.

Initially, the Face Value Program proved a great success. The Royal Canadian Mint sold $4.2 million of $20 coins at face value to customers who had previously nothing to do with coins. Its main target were younger people, which is why popular motifs such as Bugs Bunny, Superman, a dinosaur or the spaceship Enterprise were chosen.

But then the problems started: buyers tried to use these coins – Surprise! Surprise! – to buy something only to realize that they could not buy anything at all with these coins. Of course, this resulted in anger and bad publicity. The coin owners could call themselves lucky if someone paid them the silver value for their collector’s item and saved them the trip to the Canadian Mint, where the pieces were and are actually taken back at face value. The retailers, for their part, obtained a pretty profit by collecting the pieces and returning them, at face value, to the Royal Canadian Mint.

The Royal Canadian Mint has now found ways for customers to exchange their Face Value Program coins for face value at RCM with as little effort as possible and without having to resort to a middleman. Canada Post plays a vital role here.

An unwanted side effect of these returns is the fact that the Royal Canadian Mint is now left with the expenses that are incurred by the silver price fluctuations. After all, it had bought the silver in the coins, which it withdraws from them during the melting process, for a much higher price. These costs are so high that they have a significant impact on the annual budget which in 2016 was roughly $17 million smaller than in the year before.

Learning from history?

Altogether, it is a good idea to look at the past when, once again, the question arises as to how to correlate the fluctuating silver price with silver containing circulating commemorative coins. One thing is certain: there is hardly any better marketing strategy than these popular coins for beginners. Their release, on the other hand, involves risks one should know before opting for it.

This article was published originally in the December issue of Currency News 2017.