by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

August 7, 2014 – We are still in Syracuse. We are still trying to get over the huge disappointment of not being able to see the archaeological museum’s coin cabinet because the pensioner who keeps the key prefers to spend the bank holiday with his family instead of unlocking the treasure room for us. But in the end we decided to give the rest of the museum a try anyway. There was much to discover: many interesting and even more uninteresting things, masses of show cases and a lack of didactical conceptualization on part of the museum’s management, but at least also finds from Sicily’s biggest excavations.

And we also learnt something new this day, though not in the museum. Did you know that Syracuse has its own catacombs?

Friday, April 25, 2014

Today was an Italian bank holiday, something that we of course hadn’t factored in. On Liberation Day, Anniversario della Liberazione, Italy celebrates the fall of the fascist regime, which came about much earlier than in Germany.

Mussolini and Hitler on September 29, 1938, after signing the Munich Agreement.

German Federal Archives, picture 146-1969-065-24 / CC-BY-SA.

After the defeats in North Africa and especially at the Don in the winter of 1942/3, a number of renowned politicians took a stand for the end of the Berlin – Rome axis. Some of them individually began peace talks with the Allies. The social and political climate was critical. Food was only available on the black market and prices were at an all-time high, while wages had been stagnating since the outbreak of the war. Those bombed out (and many Italians were) didn’t even have a roof over their heads because the Italian government didn’t supply the necessary aid. So, many of the common people enthusiastically welcomed the Allied invasion of Sicily on July 9/10, 1943. And the opponents of Mussolini in the party leadership finally had an opportunity to act.

The Grand Council of Fascism was called, which hadn’t convened since 1939. To Mussolini’s surprise, he was deposed as commander in chief of the army on July 25, 1943. The King took over this office. And he informed the Duce that he would not only take over this office, but also depose Mussolini as Head of Government – something which had not been decreed by the Council, by the way. The crowds were celebrating – among them also countless Germans, who wrongly assumed Hitler himself had been overthrown.

Mussolini is rescued by German paratroopers in Gran Sasso. German Federal Archives, picture 101I-567-1503C-13 / Toni Schneiders / CC-BY-SA.

They were all brutally knocked out of the skies when a German paratrooper battalion rescued Mussolini from captivity and the Germans invaded Northern Italy. But the end of fascism was near. In the so-called Italian Social Republic, Mussolini only governed the north of Italy, which was invaded by the Allies in April 1945. The Duce made an escape in the night of April 25. He was captured two days later on the run and executed on April 28.

What happened to his corpse afterwards is typical of Italy’s ambivalent attitude toward that part of its national history. The Americans anonymously buried Mussolini on a military cemetery. A year later, Italian fascists dug him up again. Aided by several church officials, they hid him in various churches and monasteries for years.

Today, Mussolini rests in his family vault, which has developed into a kind of pilgrimage destination for neo-fascists. This was made possible by Adone Zoli, avowing anti-fascist and Christian Democratic Prime Minister between May 19, 1957, and June 19, 1958, who briefly secured the support of the neo-fascist party MSI for his government by allowing Mussolini’s entombment in the family vault in Predappio.

But back to our main topic, the Anniversario della Liberazione. This holiday has existed since 1946 and the Italians enjoy it as an extra day off work. We didn’t notice any special events. The streets were a little busier than usual, naturally, as day-trippers exploited the long weekend.

The museum. Photo: KW.

The museum, however, was just as empty as on the previous day.

Wooden statuettes from Palma di Montechiaro. Photo: KW.

We discovered several notable finds, although, admittedly, you had to possess a lot of archaeological expertise in order to recognise the few really precious pieces amidst the sheer never-ending masses of badly labelled objects in countless show cases. These three small archaic statuettes for instance are no common cult objects made of clay. It’s their material, wood, that makes these goddesses, found in Palma di Montechiaro, so rare.

Terracotta statue from Madonna del Piano, around 600. Photo: KW.

If you’re looking for marble in Syracuse, you’ll be looking in vain. Instead, you’ll find many terracotta statues as they were also common in Rome during the Early Republic.

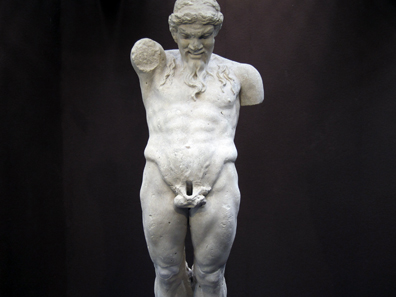

Priapus statue, second half of the 3rd century BC. Photo: KW.

The first floor offers several large-scale sculptures, mostly from local limestone. A good example is this Hellenistic Priapus, one of the earliest preserved statues of him. As we’re told by the Syracusan Theocritus, there was a cult for him as companion of Pan, god of the shepherds, in Syracuse.

Roman copy (2nd century AD) of a Venus Pudica (2nd century BC). Photo: KW.

One exception to the no-marble rule in Syracuse is the Venus Landolina. She imitates the model of Aphrodite bashfully hiding her nudity as it is found for instance in Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Cnidus. On a trip to Sicily in 1885, Guy de Maupassant examined this art work. To the French expert on women, she is the seductive epitome of all women: “This is a woman, the way she is, the way you love her, you desire her, you long to embrace her.” That this woman is missing a head doesn’t seem to bother the poet. Heads are apparently negligible when it comes to women and the art of seduction.

Nerva. Photo: KW.

A few heads of Empresses and Emperors, like Nerva here …

Little box made of lead. Photo: KW.

… a few interesting grave finds, like this leaden chest for mortal remains …

Statuettes produced by the same mold. Photo: KW.

… and these cheesy statuettes, all made from the same form, were exhibited on the first floor.

Model of the Temple of Apollo. Photo: KW.

Fascinating were of course also the finds from Syracusan sanctuaries. In a rare moment of insight, the museum’s management had made an attempt at presenting their exhibits in a didactically valuable way and put up reconstructions of the individual temples. Here’s the Temple of Apollo, which you pass on setting foot on the island of Ortygia.

Temple of Athena without the surrounding church. Photo: KW.

This is what the Temple of Athena looked like before it was turned into a church.

Lion head gargoyle in front of the Temple of Athena. Photo: KW.

It was built with local limestone and decorated with gargoyles such as this.

The elegant Ionic temple from 525 BC. Photo: KW.

To inspect this Ionic temple, you have to descend into the basement of the town hall. It may have been dedicated to Artemis.

Terracotta temple decoration. Photo: KW.

And it was decorated with female terracotta heads such as these.

Gorgon and Pegasus. Photo: KW.

We cannot reconstruct anymore to which building this magnificent Gorgon from the late 7th century BC once belonged. It is generally assumed that the effigy was fastened to a wooden wall and probably adorned a small proto-Archaic building.

Personally, I think the Gorgon is the most impressive exhibit in Syracuse – excluded, of course, the coins we weren’t able to see… (I guess I mentioned it before…) By the way, Pegasus in her right arm is a reminder that the miraculous horse supposedly jumped right out of Medusa’s throat when she was slain by Perseus.

And so we’d visited all exhibition rooms of the Museum of Syracuse – apart from the coin cabinet – in less than three hours. There was still some time left for us to visit one of the catacombs of Syracuse. All of them are worth seeing, although seeing them can be difficult. The catacombs of John the Evangelist, however, actually have something like regular opening hours by now. Nevertheless, the catacombs are still outshone by classical antiquity.

The church of Saint Marcian. Photo. KW.

Each of the catacombs in the world is named after its Roman model along the Via Appia Antica in Rome. There you can find massive, multi-storey systems of subterranean tunnels with burial niches on each side. They are first mentioned in a 9th century document as “ad catacumbas”. Scholars disagree on the exact meaning of this expression at the time of its documentation. Today, the term “catacomb” can refer to any kind of subterranean tunnel system, even if – like the famous catacombs of Paris – it originated as a quarry in the modern era and wasn’t used as a burial site until the 19th century.

Although Hollywood flicks and historical dramas set in the 19th century like to present the Christians’ flight from the authorities as the main reason for the emergence of catacombs, the historically more accurate reason was much less dramatic and more of a space problem. After all, the dead were traditionally buried along the outward roads. And those spaces became more and more crowded in late antiquity. So, where possible, one started going underground. Consequently, Rome and Syracuse are of course not the only places in Italy with catacombs. But Syracuse holds a special position as it has the most extensive tunnel system apart from Rome.

Entrance to the catacombs of Saint John. Photo: KW.

There are several catacombs in Syracuse. Those of Saint John the Evangelist, close to the archaeological museum, are probably the most famous ones. They were built near the burial site of a Syracusan saint, Saint Marcian of Syracuse, who is said to have been the city’s first bishop. His persona unites recollections of a first bishop, instituted by Saint Peter himself and who died under Nero, and a considerably later bishop, who died a martyr under Valerian.

The crypt of Saint Marcian. Photo: Giovanni Dall’Orto. / Wikipedia.

Photographs were strictly forbidden in the subterranean area, so that in order to show you the crypt we have to borrow this picture from Giovanni Dall’Orto, who either didn’t follow the guide’s instructions as obediently as we did or visited the crypt at a time when taking pictures hadn’t been forbidden yet. (If you ask me, I think it’s the former, because even this untiring photographer doesn’t provide pictures of the tunnels.)

First, we inspected the crypt of Saint Marcian, accompanied by the guide’s deadly boring explanations (repeated in several languages, on top of that!). This could easily be one of the oldest known Christian cult places. An imposing church occupied this place already in the 4th century and served as a cathedral for centuries before the Temple of Athena replaced its function in the 7th century. In the centre of the crypt was the tomb of Saint Marcian and a column, which was allegedly instrumental to his martyrdom. Further, a stone altar still designates the place where Saint Paul is said to have held his sermon on his visit to Syracuse.

Finally, daylight again! Photo: KW.

Later, we made our way through endless tunnels with single, double and family tombs, paint remnants and wall decorations. From time to time, large rotundas offered a sense of orientation, but to be honest, we always paid close attention in order to not lose the rest of our group anyway.

By the way, during World War II, the catacombs served as bomb shelters because Syracuse, with its harbour opposite the African coast, presented an important military target for the Allies, who bombed it and conquered it during the Operation Husky.

And that was it for today. The weather was lovely, there would have been so much more to see, but we preferred to spend a few quiet hours in our peaceful abode. It would be the last quiet hours once we got into Palermo the next day, that was for sure.

Stay with us for the last part of our journey, to the Conca d’oro, the “golden basin” of Palermo, which offers more sights than you can imagine in a very small area. And for once, it won’t be all about the ancient world.

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.