by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

June 12, 2014 – When planning our journey, we had decided long ago where we wanted to be on Good Friday: in Trapani, to witness the famous Misteri. Too high were the expectations built up by countless tales of the mystic atmosphere in the narrow alleyways of Trapani, the night lit up solely by fires, the men carrying the heavy sculptures, sweating and tired and the silent crowd watching, over the solemn music of a Sicilian funeral march. But as the procession wasn’t to start before Christ’s hour of death at 3 pm – we decided to ignore the various rumours about differing times spread by travel guides and on the internet – we had time to visit Erice, where once stood the Temple of the Venus Ericina.

Friday, April 18, 2014

So when we left Balata di Baida this time, we drove towards the sea, not the highway. What surprised us most was the mountain pass that lay between us and Erice. In theory we knew of course that the city was located at more than 700 m above sea level, but it took us longer than anticipated to conquer those. Especially being stuck behind three huge tour coaches. Turned out we weren’t the only ones on our way to Erice. But how should it have been otherwise? After all, the rumour that the passion procession in Trapani is more than worth seeing must have been going around for a while now. And apparently we also weren’t the only ones to connect the trip with a visit to Erice.

But the ancient city of Eryx can take them all. Parking lots exist in plenty, even if hard to locate at times. The fare system is remarkably differentiated, so the parking lots just off the city’s main entrance gate charge fees all year round, the ones a little further off only during the preseason and high season, and those really quite far off – one of which we discovered accidentally by taking a wrong turn – only during the high season. And so it happened that we parked our car comfortably and free of charge for the whole day, even if it took us a few rather interesting detours to reach the touristic city centre.

A yellow sign informed us that we parked right next to the former elymo-Punic city wall. Photo: KW.

I say interesting because nowadays Erice is very sparsely populated. There is no lack of guest houses, restaurants, deliciously smelling pasticcerias and souvenir shops. But actual apartments and real people are hard to come by. It seems like all the blocked-up houses are only inhabited in midsummer when their rich second home owners flee baking hot Palermo and take refuge in cool Erice.

Erice’s alleys are only ever peopled by tourists. Photo: KW.

No wonder, as the city is pretty far off the beaten track. Apart from a police station, schools, daycare centres and other social services providers were absent. It appears much more sensible and economically advantageous to sell your house to a rich Palermitan and move down to Trapani. Due to its exposed location, a constant wind blows around Erice, which is slightly unpleasant in April, but must be pleasantly refreshing during the summer.

Castello di Venere. Photo: KW.

After several detours we arrived at the famous Castello di Venere, located in the spot where the Temple of Venus had formerly stood. But more about that later. Let’s begin with some historical information about Erice, the ancient city of Eryx. It is surrounded not by one, but two founding myths.

Diodorus writes about an eponymous hero named Eryx, son to Aphrodite and Poseidon. This Eryx lived in western Sicily and stole a lost cow from the herd of Geryon, a giant with three bodies joined to one pair of legs. Heracles was of the opinion that he alone should have the right to bovine theft (in the end he stole Geryon’s entire herd) and challenged Eryx to fight him in a wrestling match. We all know how that ended. The Hellenic hero strangled the unwanted rival.

The Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodius tells a quite different story. One of the Argonauts, so it goes, fell overboard when captured by the sirens’ song. But Aphrodite had pity and carried him to Eryx.

Eryx. Didrachm, 420-416. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 215 (2013), 681.

Be that as it may, there is one aspect on which historians of Greek Antiquity agree: Eryx was a city of the Elymi. Other than that, we don’t know much about its destiny prior to the 4th century BC.

Eryx. Bronze coin, 400-340. From Künker auction sale 133 (2007), 7139.

One of the few things we do know is that it was highly contested due to its favourable location. First it was brought under the rule of Dionysius of Syracuse in 397, then it was taken by the Carthaginians. Even Pyrrhus himself is said to have been present when the city changed hands again, although soon after, at the beginning of the Punic War, the fortification was already back under Carthaginian rule.

Siculo-Punic coin. Tetradrachm, 320-310. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 185 (2010), 54. – Some numismatists claim to see Venus Ericina in the head on the obverse, or, as the Carthaginians called her, Astarte-Tinit.

In 260 BC, the Carthaginian general Hamilcar commanded the city’s destruction in order to resettle the denizens to Drepanon – now Trapani – because it was easier to supply with provisions. However, not all inhabitants seem to have followed his command: several years later, Roman consul L. Iunius bragged about taking the city and the temple in a surprise attack. Of course, a Carthaginian counter-attack followed. The Romans held the temple and the fortification on top of Mount Erice while the Carthaginians cut off the enemy’s supplies by occupying the city below. It would only have been a matter of time until the Carthaginians would have regained the rule over Eryx, if it hadn’t been for the peace of 241 and their subsequent withdrawal from Sicily.

C. Considius Nonianus. Denarius, 56 BC. From Wyprächtiger collection / From MoneyMuseum collection.

The denizens of Eryx led a relatively comfortable life under the Roman rule as the Elymi were traditionally considered Trojans. And their main sanctuary was a Temple of Venus – and after all, Venus was mother to Aeneas, progenitor of the Roman people. Sounds like a big family to me …

No Roman magistrate forgot to pay a visit to the temple. The Romans set up a guard of honour and demanded annual gold contributions from 17 Sicilian cities for the maintenance of the temple. In the early 1st century AD, though, the shrine fell into decline and the priests under Tiberius asked for financial support of the restoration. The support was granted. And that is the last mention of the Temple of the Venus of Eryx.

In Rome, however, the Venus Ericina continued to be of importance. Two temples were even dedicated to her name: one built on the Capitoline Hill, in 217 BC, and one on the Quirinal, near the Porta Collina, built in 181 BC.

Resting Venus by Dirck de Quade van Ravesteyn. KHM. Source: Wikipedia.

Apropos, a word on sacred prostitution on Mount Erice. More recent scholarship has proven that such practices only existed in guide books and the travellers’ fantasy. In his research from 2009, Martin Lindner couldn’t find as much as one contemporary piece of evidence to attest such practices among the Elymi or the Carthaginians. Later sources seem to have spread not a historical truth, but rather a stereotypical fantasy which connotes the exotic with the erotic. Which strikes me as a pretty current issue.

Castello di Venere. Photo: KW.

Anyway. Despite the many tourists bustling around Erice, we had the Castello all to ourselves. A remnant from Norman times, it was constructed in the 12th century, when the mountain was being resettled and renamed Monte San Giuliano.

Above the entrance: coat of arms of Charles V of Spain. Photo: KW.

Continuing excavations in the fort are financed by a foundation.

The Wall of Daedalus – or so the signs inside the fort say. Photo: KW.

Let’s admit it. Despite all the efforts by those in charge to turn the fort into a spectacular sight – a Roman wall from the 4th or 3rd century BC is stylized as the Wall of Daedalus – it is unlikely to excite anyone but those who have enjoyed the sight of the Venus temple on the coins of Considius Nonianus many a time before. (Guess which of the two categories we belong in …)

Place of Venus’s ritual bath. Photo: KW.

We couldn’t help but smile to ourselves about a sign-board informing visitors that Venus had taken her legendary bath in this particular well, maybe from Phoenician times. At least the follow-up sentence honestly admitted that scholars thought it more likely to have been a granary and, at a later stage, probably a cistern.

Flowers on the excavation site. Photo: KW.

Still we dutifully inspected each single stone and, to be honest, found the flowers at least as lovely.

The Duomo dell’Assunta in Erice: An architectural disaster (if you ask me). Photo: KW.

After we took a delicious lunch, consisting of various starters and afters, in a little bistro, we ended up in the Duomo dell’Assunta, the former cathedral of Erice. From the outside, it didn’t look half bad, a Romanesque edifice with an impressive portal. The inside, however, must be the nightmare of each and every restorer: every inch of the interior walls is covered in stucco, imitating an exaggerated form of Gothic reticulated vaulting. And for that they charge admission!

There was no sign of it being Good Friday or there being a service, for that matter. Only reminder of the church’s original function: the priests, not only the tour guides, were for free.

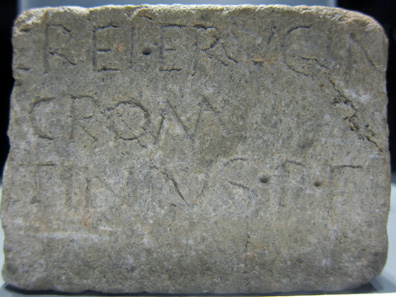

Inscription dedicated to the Venus Ericina; first line: EREI ERVCIN. Photo: KW.

Our last stop before the procession was the archaeological museum of Erice – small, but set up with great care. Not only was there a dedicatory inscription to the Venus Ericina …

The museum also reserved a spot for numismatics. Photo: KW.

… but also a show case with excavated coins, although the city’s precious tetra- and didrachms were only present on photographs. The show case was equipped with rather shabby bronze coins.

Forsaken barracks with a heroic statue at the entrance. Photo: KW.

The cable car that, after having been out of operation for decades, again transports tourists from Trapani up to Mount Erice and back, is an unmistakable sign of Sicily’s self-understanding as a modern tourist destination, willing to afford its guests every possible comfort. So I had a brilliant idea – or at least that’s what I thought at the time: wouldn’t we get horribly stuck in traffic in Trapani, which was determined to be chaotic, what with people coming in from all over Sicily to see the big passion procession? And wouldn’t it be much smarter to leave our car safely behind in the parking lot and use the cable car and then walk the rest into the city centre? Seen from our lofty vantage point, it couldn’t be that far after all!

Well, turns out, it could. Isn’t it funny how sometimes being on just 700 m is enough to considerably distort the perspective! We walked some 3 km through desolate housing complexes, decorated with unambiguously ambiguous graffiti, and past barracks until we finally reached civilization again.

Balloons, especially pink ones, play an important role in Trapani on Good Friday. Photo: KW.

Here all indication was that a big spectacle was about to happen, although the link to Good Friday seemed to be somewhat amiss. Salesmen on all sides offered their colourful balloons. Gigantic stalls were overflowing with sweets. Neither shops nor bars closed on this holy day, which, expecting crowds of tourists, seemed to promise economic rather than heavenly blessings.

Propagandistic election posters in Italian; Germany currently doesn’t seem to be a particular favourite of the Italians. Photo: KW.

Apparently everybody knew where the procession would take place as there wasn’t a single sign indicating the location.

A glimpse at the procession and its audience – mind you, it was relatively empty at this time of day still! Photo: KW.

So we kept going towards the sea and, finally, after walking for almost an hour, perceived the solemn funeral music, to the rhythm of which the procession’s participants swayed in unison. Yes, swayed. The faithful don’t walk like other people, they slowly and rhythmically shift their weight from left – to right, from left – to right … An especially welcoming sight are the children in the procession, who visibly struggle with this way of moving forward and instead find their own rhythm or simply sway in the opposite direction.

Before I begin, I’d like to mention one thing: the procession would have been quite moving if the bystanders had actually taken it a little more seriously. But it was fairly obvious that most of the spectators were either unaware of the event’s religious background or simply didn’t care too much about it. We’d managed to secure a very good spot, just in front of an ice cream parlour (which was, of course, open). You couldn’t help but develop a certain fascination with this scenario, the sharp contrast between the crowds, gaily romping about, licking their ice cream, being merry and making phone calls and the scenes of the Passion of Jesus Christ. Only few people (of higher age) stood watching. Right next to me a lady of some 60 years of age and not taller than 1.55 m was genuinely upset because spectators continuously passed by in front of her, effectively barring her sight on the procession completely.

Even with the advantage of my height, I had to make quite an effort to remain stoically in my spot and not be pushed left and right by bored passers-by, ambling along the procession. Reverence? Devotion? Such pious feelings were hardly detectable in the procession’s participants themselves. It was quite a sight how some of the participants in the procession irreverently took out their cell phones and made a call in the midst of this sacred spectacle.

Bearers suffering under their heavy burden. Photo: KW.

To be fair, the path wasn’t as easy for everyone. Especially those bearing the stations of the cross looked as if they’d seen happier days, when heaving the weighty statues along the streets.

The crowning with thorns. Photo: KW.

The groups are arranged according to themes, …

Here come the bricklayers and stonemasons. Photo: KW.

… portrayed by the old guilds which continue to exist only for this purpose. A flag with the relevant Bible quote precedes each group.

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

Followed by women and especially by many, many children carrying candles, flags, flowers and symbols.

Flagellation. Photo: KW.

Ecce Homo. Photo: KW.

Followed by the portable stations of the cross …

A band – notice how the bandleader is on the phone. Photo: KW.

.. and right after, the band which provides the background music.

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

Each group was of course trying to depict its own station in more colourful and spectacular images than the others.

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

The prettiest young women take a place of honour …

Scenes from the passion procession. Photo: KW.

… (and I am certain that the annual selection is regularly accompanied by jealous girls making a scene).

Admitted, we didn’t stay to see the whole procession. After several stations, a certain uniformity could be observed and the visitors pushing and shoving their way through the crowd didn’t make the situation more comfortable either. Although we’d been late for the opening of the ceremony, we still arrived a good deal earlier than the bulk of spectators. When we made our way back to the cable car around 7 pm (yes, still a three kilometre hike, only uphill this time), the biggest obstacle were the crowds of people pouring in towards the old town. We were swimming against the tide. I assume crowds really fall in at night to see the passion procession in Trapani. How the active participants of the procession will be able to make their way through the crowds, however, is beyond my imagination.

For an experience with some of the event’s original pathos, I recommend this video on YouTube, which intercuts images from this year’s procession with historical footage.

And this gives you an impression of the nerve-wrecking music accompanying the procession.

And here ends our story for today. It was late. So late that we neither wanted, nor got dinner anymore.

Stay with us for the next episode of our numismatic diary “Sicily in full bloom” and travel to Selinus to find out why Sicily’s landscape is so green and its fields filled with blossoming flowers at this time of year.

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.