by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

May 15, 2014 – Next year the International Numismatic Congress will take place in the charming little city of Taormina, which these days attracts large numbers of tourists. The ancient city, called Tauromenium at the time, became a reception camp for survivors after Dionysius I of Syracuse destroyed Naxos in AD 358. Follow us into the past …

Monday, April 14, 2014

Eugenio, our host, was still overwhelmed by last night’s excitement of showing us his coins. While we were getting started with our breakfast, he hurried out of the kitchen just to thank us again in person. On this occasion, he told us much about life in Italy, his business and the things he worried about. His orange plantations, not the agriturismo, are his main source of revenue. He can’t sell his fruits in Sicily because the local price wouldn’t even cover the production costs. Until last year, he used to charter a lorry together with several other local farmers and used to drive to Great Britain and sell their oranges directly. But this didn’t quite work out anymore. So he was planning to drive to Western Europe this summer to investigate other possibilities of directly selling his goods. (Should you have close connections to supermarket owners interested in premium quality oranges, I am happy to introduce you!)

Italian breakfast: two croissants, butter and jam, with coffee or tea. Photo: KW.

No, his children weren’t interested in the family business, he told us. They didn’t even live in Italy anymore. Two had emigrated to Australia because they quickly found jobs according to their qualification. Pretty much all well qualified people were leaving Sicily these days. He could understand that. He did love his country, that’s for sure, but the pollution? Unbearable. People were leaving their trash behind everywhere and the state didn’t lift a finger to do anything about it. That was the main problem. As soon as the state got involved, things weren’t taken care of properly. Personally, he had to keep his books clean due to his membership in the cooperative, but he could understand why many highly qualified craftsmen worked under the table. Why pay taxes if the state didn’t put them to any good use? And so on and so forth.

Then he switched to the EU. The standards were almost impossible to fulfil and he’d had enough of it. He couldn’t sell his own quality products on the official market anymore because all the examination procedures were much too expensive for a small business like his. At least his oranges were certified as organic products so he could sell them abroad without problems. But his olives – he didn’t grow large enough an amount in order to compensate all the effort.

I think we learned more about the country and its people from Eugenio during this one-hour breakfast than we could ever have in a book! And I made the firm resolution to eat the oranges from my supermarket with greater respect in the future!

Our little friend, the Mediterranean house gecko (hemidactylus turcicus), was waiting for us morning and evening in a massive concrete pipe when we came through the gate to the Masseria. Photo: KW.

Actually we had planned a Mount Etna round trip for today but the mountain was (unsurprisingly) covered in clouds. In general it looked pretty rainy and we weren’t exactly keen on standing on the top of Etna in the pouring rain …

The picturesque bay of Taormina in a slightly less picturesque rain shower. Photo: KW.

So we took off to visit Taormina straightaway, which turned out to be the right decision because the rain was coming down in sheets around Mount Etna. Having mastered the heavy traffic in Catania, we took the highway to Taormina and arrived an hour later.

In a proper car park! Like they have them in the big cities in Germany! We hadn’t forgotten the car renting agency’s warning about how every second Smart in Sicily was stolen so we were genuinely relieved. You’ve got to hand it to the Taorminesi, they’ve organised their city effectively. A necessity, considering the masses of visitors it attracts every year. All of which arrive in vehicles ill suited for the town centre’s narrow streets. So there are two car parks at the main entrances to the old Taormina and you can take a shuttle bus going directly into the city centre. That is, if you knew which bus was going where. But once again, the Italians don’t seem to bother too much about publicly displaying such marginalia.

To this day, we have no idea where these seemingly endless stairs lead. Photo: KW.

Instead, I found a stairway to the city centre that we climbed up, panting hard. And then there was another stairway. We climbed that too. And another, and another, and after what felt like 3,000 steps we just wanted to know where this stupid stairway was going!

We never found out. After an hour and some 200 metres ascent we came onto a proper road which we walked down again. Turns out we should have gone left instead of right just after the first 50 or so steps and it would have led us straight to the Greek theatre. Oh well.

Tauromenium. Bronze, after 336. From Gorny & Mosch auction 216 (2013), 2185.

Although the Sicels had settled on the mountain of Tauromenium already in the late 2nd millennium and entertained friendly relations with the Greeks who had founded Naxos in 734, Taormina’s rise to fame began only with the demise of their greater neighbour. Naxos was destroyed by Dionysius of Syracuse in 403. The surviving citizens left their hometown and settled in the safety of Tauromenium.

Tauromenium. Bronze, after 336. Left of Apollo’s head the inscription ‘Archegetas’. From Fritz Rudolf Künker auction 236 (2013), 421.

Tauromenium must have been expanding rapidly after the downfall of Naxos. It would explain why Timoleon chose the city’s harbour to anchor ship when he landed his small army on Sicily during his campaign. At the time the region was ruled by Andromachus, an allegedly very friendly and wise tyrant despite his title, whom Timoleon allowed to remain in office because of his ability. (That Andromachus had supported him from the start probably also helped.)

Tauromenium. 4 Litrai, 274-216. From Peus Nachf. auction 407 (2012), 268.

Anyhow, we don’t know very much about Tauromenium in the 4th and 3rd century. At times the city was independent, at times under the control of Syracuse and was thus brought under Roman rule in the Second Punic War. A comment in the writings of Appian implies that the citizens of Tauromenium, by surrendering, were able to negotiate generous peace conditions. At least Cicero reports that Tauromenium was one of the three Sicilian cities allowed to maintain their status as “civitas foederata”, which granted very rare and highly coveted privileges.

Tauromenium. Bronze, after 211. From Peus Nachf. auction 412 (2014), 53.

Under Roman rule, the already secure stronghold was further fortified. Large cisterns were built whose content, if filled to capacity, could provide water for Tauromenium’s citizens for two years. During the slave uprising from 134-132, the rebels hid out here. Only hunger forced them to surrender.

Sextus Pompeius, + 35. Denarius, 37/6, Sicilian Mint. From Künker auction 243 (2013), 4694.

Taormina also played a major role for Sextus Pompeius. To him it was one of the most important strongholds on Sicily. It was here that he crushed Octavian – who led his fleet in person – in a sea battle. A few years later, the future founder of the Pax Augusta decided to drive the Taorminesi off their lands and establish a Roman colony. Taormina continued to thrive, only this time its citizens spoke Latin, pressed excellent wines and fished the best grey mullets around, we’re told in one of Juvenal’s poems.

During the Byzantine Empire, Taormina again increased in importance. After the downfall of Syracuse, it remained the last major base of the Byzantine emperor in his fight against the Arabs. The city wasn’t conquered until 902, but after it repeatedly became the centre of uprisings it was completely destroyed in a rebellion and rebuilt as “Al-Muizzia” in 969.

From then on, Taormina was brought first under Norman, then under French and finally under Spanish rule, just like all other Sicilian cities. When a road was built from Messina to Catania in the 19th century, it seemed like Taormina’s fate was sealed. The road went a little too far into the island’s interior and cut off Taormina from the main traffic. In the end, it was the best thing which could have happened to the beautiful little town. It remained unaffected by the impact of industrialisation and developed into the internationally renowned touristic travel destination it is today.

Photography by Wilhelm von Gloeden from 1890/5 with the title ‘Amore e arte’ (‘Love and art’). Source: Wikicommons.

Although Goethe had visited Taormina on his tour of Italy, the city became famous only when the German Wilhelm von Gloeden came to Taormina in 1878 to cure his lung disease. If Mr Gloeden did what he was doing back in the days in present day Germany, he would definitely get in trouble with the police. He took erotic photographs of Sicilian youths and staged them artistically with antique props, skilful lighting and highly effective body paint as his modern vision of Arcadia.

In the late 19th century, the intellectual avant-garde was enthralled with his works. Promptly Gloeden proclaimed himself a baron, invented an illustrious past with a father in the army and his birth place a castle near Wismar, so that his studio was even listed as a place to visit in the “Baedeker”. This mention didn’t attract only Oscar Wilde, but other, more respectable clients such as Alfred Krupp, Richard Strauss or German Emperor William II. (To protect the honour of these gentlemen, let’s just assume that they were only interested in Gloeden’s portraits of the dressed (!) local underclass. The nudes were probably sold to close friends and great admirers under the table only.) Marketing the pictures as postcards brought Gloeden, his Arcadia and Taormina a fame which established it as a must-see for package tourists.

Photography by Wilhelm von Gloeden: ‘Madonna’, 1890s. Source: Wikicommons.

By the way, Gloeden was very popular with the poorer citizens of Taormina. He didn’t only pay his models for posing but also set up accounts for them and paid in a share of his profits. He liked to help out financially whenever he could and was thus generally well-liked by the population despite his homoerotic inclination. The fascists weren’t quite as tolerant. The majority of von Gloeden’s photographs was destroyed by Mussolini’s regime on the charge of pornography. Today the largest collection of his works is archived in Berlin at the Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte (“Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory”).

Souvenir shop in Taormina. Photo: KW.

Most conversations in Taormina’s bars today are conducted in German, English, French, Russian and sometimes even Italian (among the waiters). There is barely a house in the whole of Taormina which does not include a hotel, restaurant or souvenir shop. And despite all that, the theatre with its ocean view remains a magical place to stay and forget the time.

The theatre of Taormina. Photo: KW.

So that’s what we did. After our adventure on the 5,000 steps into nowhere and the neverending Via Leonardo Da Vinci into the city centre, we eventually discovered the tourist information and a city map, which informed us that we were close to basically all sights.

We arrived at the theatre – fortunately before the host of cruisers (15 groups with 30 tourists each). The theatre of Taormina is often quoted to illustrate the differences between Greek and Roman theatre: “Taormina was so perfectly fitted to the landscape that the ocean played a major role in almost each performance (etc.)” However, the ruins still visible today are in fact almost exclusively Roman. And if you imagine the skena which raised behind the stage once, you will realise that a historical audience – at least those not seated in the upper, cheaper rows – probably didn’t see much at all of the scenic landscape. Lucky for us, a yawing hole in the middle of the stage opens up to a stunning view today. A view which makes you forget that in Roman times the theatre was primarily a venue for bloody fights between gladiators and animals.

The small odeion. Photo: KW.

Later we had a break in one of the small bars almost entirely populated by German tourists and various travel groups. A shared frustration about the inflexible programme and the resulting disappointment of having seen so little of Mount Etna in the bad weather united people across table boundaries. Once again we were happy to be making our own programme.

We had originally also planned on seeing the cathedral, but the incessant rain convinced us otherwise. After all, we will have plenty of opportunities to discover every corner of Taormina during the International Numismatic Congress in 2015.

You can already register for the Congress now – just visit this website.

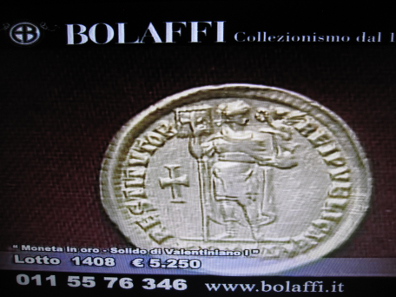

Why not? Selling ancient coins on TV. Photo: KW.

On our arrival at the masseria we still had some time to kill before dinner. But what did we see? Ancient coins again, this time on TV. You could buy a solidus of Valentinian I for 5,250 euro, a sesterce of Antoninus Pius for 1,500 euro and many more.

A major player on the Italian market for cultural artefacts. Photo: KW.

I will admit that I know a few Italian coin dealers, but I had never heard of a company Bolaffi before. Google told me that the company, founded in 1890, doesn’t only sell numismatic objects, but also stamps, rare books and autographs, furniture and more. Four flagship stores are located in Turin, Milan, Verona and Rome. And the company’s homepage is available in Chinese and Russian. Intriguing.

No, that’s not a tomato salad. Photo: KW.

Not intriguing, but remarkable was the dinner served by Eugenio and Marysa that night. Four courses of local delicacies. The starter was an orange salad, yes indeed, sweet oranges with spring onions, celery and black olives, dressed with oil and vinegar. Simply delicious!!!

Marysa grating fresh ricotta, an indispensable ingredient for Pasta alla Norma. Photo: UK.

The first course was a typical Sicilian dish, Pasta Norma. The colours of the five ingredients – penne, aubergine, tomato, fresh basil and ricotta – are interpreted as signifying a combination of the Italian tricolour (green, white, red) and the colours of the city Catania (white, black). Two legends surround the origin of the dish’s name: what we know for certain is that the pasta was named after the opera “Norma” by Catania-born composer Vincenzo Bellini. But whether you want to believe that the cook was so infatuated with Bellini’s opera that he named a dish after it or whether you prefer the explanation that the phrase “una vera norma”, a common Catanian superlative, was simply used to describe the pasta is up to you.

Costoletta and fennel gratin. Photo: KW.

For the main course, Marysa served costoletta, marinated in Marsala and accompanied by fennel gratin. Costoletta is an Italian term for breadcrumbed veal cutlet, and costoletta alla Milanese (recipe here) simply a “Wiener Schnitzel”.

For the main course, Marysa served costoletta, marinated in Marsala and accompanied by fennel gratin. Costoletta is an Italian term for breadcrumbed veal cutlet, and costoletta alla Milanese (recipe here) simply a “Wiener Schnitzel”.

Cannolo. Foto: KW.

The grand finale of our Italian feast were the famous Sicilian cannoli. The word’s etymology is the Latin word “canna” – pipe, which refers not to the pastry’s shape but to the pipe that is used to wrap the dough around before frying it. So cannoli are fried dough rolls with a sweet, ricotta-based filling. Originally, the sweet pastry was a Palermitan specialty only eaten during the carnival. But those times are long gone. Today there isn’t a pasticceria on Sicily that doesn’t offer this rich delicacy.

I also don’t want to miss out mentioning how much this truly princely feast, including wine and water, cost us: 18 euros each.

Sadly, that was our last night staying with Eugenio and Marysa. Next morning we would continue our journey to another agriturismo between Palermo and Trapani. From that base we would visit Selinunte, Monreale, Segesta, Motya and witness the great Good Friday procession in Trapani. So don’t miss out the next episode of “Sicily in full bloom”.

And in case you want to visit Eugenio and Marysa on your holiday trip: here’s the link to their agriturismo. Just don’t forget to tell them in advance the exact time of your arrival.

And here you can find all episodes of “Sicily in full bloom”.