by Ursula Kampmann

translated by Teresa Teklic

August 21, 2014 – Have you ever been to Palermo, that beautiful city full of contradictions? The cab driver who drove us from our hotel to the train station put it like this: we’ve seen the Carthaginians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Moors, the Normans, the French and the Spanish. How can you not expect chaos?

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Today we returned our Smart. Despite the many potential dangers of the unpredictable Sicilian traffic, it had survived without a scratch. We decided to return the car in Palermo, where we wanted to spend several more days because Palermo’s cultural heritage is so rich that stopping by on the way just doesn’t do. All those who once settled here left behind traces. And they all tried to bring Sicily under their rule. After all, although you may not believe it if you see the country today, Sicily was once rich, so rich that tax income was high enough to realise even the most ambitious plans.

Panormos. Tetradrachm, around 300. To the right, quadriga, inscription in the exergue Rsmlqt. Rv. Head of the Tanit, after Syracusan model, to the right, surrounded by four dolphins. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 159 (2007), 54.

The first ones to try and redirect the island’s riches to their home country were the Phoenicians. They came from Tyre to build their first trade imperium on Sicily in the Palermo area and are mentioned by Thucycides, who talks about a Phoenician triangle consisting of Panormos, Motya and Soluntum.

At first, the relationship between Carthaginians and Greeks was good. After all, they had both come to exploit Sicily’s riches. The Greeks entertained a flourishing trade with Palermo and renamed “Mabbonath”, as the Carthaginians called the place, Panormos, “complete port”.

Roman Republic. Denarius, 125 BC. Rv. Jupiter in elephant biga, Victoria bringing a wreath from the left. From Künker auction sale 204 (2012), 435.

During the first Punic War, the Romans conquered Panormos. When trying to undo this, Hasdrubal only helped the Metelli, one of the most powerful Republican families, to another victory and a new signet: the elephants they’d captured from the Carthaginians were proudly shown off at the triumphal procession in Rome.

Panormos. Aes, around 210-201, Magistrate Naso. From Künker auction sale 248 (2014), 7085.

Panormos was doing fairly well under Roman rule, although the praetor in charge of the Province Sicilia resided in Syracuse. But then maybe that wasn’t a bad thing after all, considering the greed for money displayed by Roman officials such as Caius Verres. There are no visible traces left around the city from this chapter of its past. The Carthaginian, Greek and Roman leftovers kept erasing each other throughout history. And – as we found out immediately upon arrival in Palermo – the Museo Regionale Archeologico Antonio Salinas has been shut down, so long ago that the hotel’s staff didn’t even remember a time when it was still open.

Italian idyll. Photo: KW.

So, no ancient treasures for us in Palermo. And soon we learnt to appreciate the museum in Syracuse anew, despite its closed coin cabinet! Be that as it may, we decided to take a stroll around the city to get a feel for it.

First piece of advice: look down while you’re walking. Palermitans don’t know the concept of poop scoop. Second piece of advice: look out for the next car that is trying to run you over. Traffic in Palermo can be tricky. And third: don’t let yourself be pushed off the pavement by the crowds taking a Sunday walk. Cars passing by hit you harder than elbows of passers-by.

Church of San Domenico, the Pantheon of Sicilian bourgeouisie. Photo: KW.

Easier said than done. We found it hard to follow our own advice and, accordingly, our excursion to the city centre turned out a rather short enterprise. We made it to the Church of San Domenico, also referred to as the pantheon of the Sicilian middle class.

Michele Pandolfini (1804-1861). Photo: KW.

We came across names of men never heard of before, whose role in history could sometimes be elucidated with help of the internet. Michel Pandolfini for instance, was Professor for Pathology at the University of Palermo and author of an influential textbook at the time. Besides, he was politically active and fought on the side of the nationalists during the revolts of 1848 and 1860.

All of those whose graves we passed were once important men. And we’d never even heard of one of them. What do they say? Fame is fleeting …

Above the roofs of Panormo (or should we say Pa-nois-o?!); I’m absolutely certain, on the left balcony on the second floor of the yellow house there must have been a massacre in the night of April 27. At least that’s what it sounded like. Photo: KW.

This night, we thought about renaming Panormo into “Pa-nois-o”. (NB: The German pun is much funnier but doesn’t translate well into English …)

Sunday, April 27, 2014

But let’s continue our discovery of Palermo’s history. After Belisarius’s victory against the Goths during the Migration Period, the Byzantines held their position until the beginning 9th century. Then came the Aghlabids from Tunisia and dropped anchor in Mazara del Vallo. After a long siege, they finally conquered Palermo, which then became seat of the Emir of Sicily.

Palermo. Abu Ishaq Ibrahim II ibn Ahmad, 875-902. Robai 881 (= 267 AH). From Künker auction sale 137 (2008), 3782.

The Aghlabids heavily influenced Palermo. The island flourished under their rule. Palermo must have been bigger than all other Christian cities in the Occident at the time. It was connected to the Islamic trade network, growing and trading with fruits imported by the new rulers: sugar cane, cotton, lemons, oranges, aubergines, artichokes and rice.

Scientists in Palermo studied books that were now made of paper, not of animal hides like before. And they studied everything written by other scholars, no matter if Christian, Jewish or Islamic.

When the Normans invaded Sicily in 1061, they found a highly developed country, whose comforts were appreciated by the new rulers. They kept the Arabic physicians and builders, cooks and astrologers. Rough Northerners turned into bon vivants with an appreciation of the comforts of a summer palace, like the Zisa.

Zisa, exterior view. Photo: KW.

We were still somewhat tired when we set off for our first sightseeing Sunday morning. The Palermitans seemed even more tired than we. Almost no Italians in the streets after the previous Saturday night’s excesses.

So we took our time and enjoyed our leisurely 45 minute walk to Zisa. The castle derives its name from the Arabic “Aziz”, which means dazzling. The building, which is regarded as one of the most beautiful edifices “that has been preserved from all of the Fatimid epoch” by experts, deserves its name. Significantly, it wasn’t a Muslim who gave the order to build Zisa, but a Norman from the Hauteville family, William I, or also William the Bad. We’ll talk more about the history of the house later, when we visit Palermo Cathedral.

Fountain hall. Photo: KW.

Anyway, when William I died, the construction of Zisa had neared completion. Back then, it was embedded in a gorgeous park and reflected itself in a large water basin, which is still preserved today but empty. So it takes imaginative powers to hear the quiet purling of the water in the gutters connected to the basin and the feeling of refreshment it must have provided on hot summer days. (Minor difficulty: it wasn’t exactly hot when we visited the place …)

Brass basin. Photo: KW.

Luxurious metal works helped to picture the castle’s former splendour.

Tombstone of Anna, mother of priest Grisanto. Photo: KW.

A tombstone from 1148 documents how international Palermo was. A priest named Grisanto had it put up in honour of his mother. And so everyone could read the inscription, he wrote it in Arabic, Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

Representative room on the first floor. Photo: KW.

On the first floor, a group of Dutch tourists drove us crazy. Obviously very educated people, who had an educated conversation about how to interpret the room’s architecture. Only we really wanted a picture of the room without the Dutchmen. To make us happy, it would have sufficed to step out aside for 20 seconds or so and let us take our picture. But apparently we didn’t voice our wish vigorously enough. They kept standing in our way debating and debating and debating. As I said, in a very educated manner, very thorough and incredibly annoying. But even with their level of expertise, they eventually ran out of things to say about the room’s architecture. By eventually I mean after half an hour. So we finally got our chance to a Dutch-free view of the representative room on the first floor.

The less representative queue in front of the Capella Palatina. Photo: KW.

Later that day, we would have happily taken our small group of Dutchmen back in exchange for the chaotic crowds of people queuing for the Capella Palatina at the Palazzo dei Normanni. We almost turned on our heels, but then we decided to look at the situation less emotionally. We wanted to see the Capella Palatina. We got there around lunchtime. Usually, lunchtime is the best time to visit otherwise heavily frequented tourist attractions. Besides, no cruise liner tourists were currently around, but they would be in the following days. So we bit the bullet, joined the queue and just when we were about to give up hope, entered to see the palace and the Capella Palatina.

“Roger’s room”. Photo: KW.

After a host of largely uninteresting or closed rooms we came to Roger’s room, in which – of course extensively restored – the gold mosaics and Cosmati from the founding time (around 1160) have been preserved. Already the fact that the room is the oldest non-sacral room that exists in its original form until today makes it invaluable.

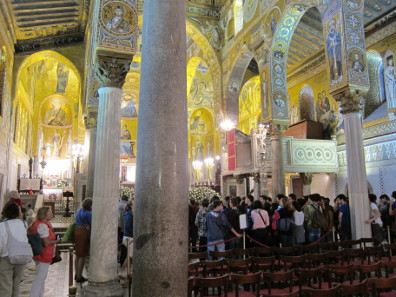

The Capella Palatina. Photo: KW.

But it would get even better, at least that’s what we were told. The Capella Palatina was described by Guy de Maupassant as “the most beautiful that the human mind has ever conceived and turned into reality, the jewel among all churches”. I don’t expect the French traveller was being pushed around by other travellers in the 19th century as we were in the 21st while trying to glimpse the beauty of the mosaics.

Detail from the mosaics dedicated to the Old Testament. Photo: KW.

In a nutshell: the mosaics are gorgeous. You could fall in love with the images’ attention to detail, as for instance with the depiction of the Tower of Babel. Not only can you see the chalk being compounded, but also which tools the builders in the 12th century did their work.

View of the altar and the holy family. Photo: KW.

However, the overall impression in magnificent gold is created by filling missing spots with mosaics of doubtful quality. So the glorious, Byzantine mosaic of Virgin Mary above the altar is juxtaposed with a rather unimportant depiction of Joseph and the holy child from the 19th century.

Wooden ceiling. Photo: KW.

An often completely neglected attraction is the Arabo-Norman wooden ceiling, which is simply too high up in the room to receive the appreciation it deserves. It is decorated with familiar scenes from court life and there is an incredible vibrancy to the pictures, that is, if you could see them…

By the way, it is thanks to a Swabian patron that the Capella Palatina today again shines with its former glory. The Würth Foundation provided the means for the appropriate restoration of the World Heritage Site.

The Cathedral of Palermo. Photo: KW.

After a light – and very touristic – refreshment we continued to the Cathedral of Palermo. It was built in the years after 1184 and deformed beyond recognition in the early 19th century.

Interior of the Cathedral of Palermo. Photo: KW.

What happened was a plan to modernise the cathedral. The medieval basilica was topped with a classicist dome and the interior disfigured so completely that most visitors don’t spend more than 10 minutes on average in there.

Porphyry sarcophagus of Frederick II. Photo: KW.

Only those familiar with Sicilian history won’t miss out on the burial site of the Norman kings. After all, the Cathedral of Palermo also houses relics of German history, the bones of the great King Frederick II, the boy from Apulia, who sold his imperial power in the Holy Roman Empire to highest bidder so he could keep his beloved kingdom of Sicily.

Roger I, 1072-1101. Trifollaro, Mileto. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 221 (2014), 3083.

Frederick was a descendant in a family of Norman rulers, who had governed Sicily since the end of the 11th century. Ancestor of the dynasty was Roger I, youngest son of Tankred of Hauteville. Because there was no chance of him getting an inheritance, he listened attentively to the stories of his brother, who had fought for the Byzantines in the Italian South. He said it would take only a few brave men and a lot of courage to conquer Sicily and build one’s own kingdom on the island. And Roger I did indeed bring an important part of the island under his control by conquering Palermo. He began to slowly drive out the Muslims, an enterprise that would only be completed by his great-grandson Frederick II.

Porphyry sarcophagus of Rogers II, 1095-1154. Photo: KW.

Roger I was succeeded by Roger II, who, with a little bit of Papal support (Roger II took advantage of the Great Schism), crowned himself King of Sicily. Roger II was that much admired ruler, whose court was famous for its flourishing academic life. Together with the assizes of Ariano he laid the foundations of Sicilian law. Significant edifices were built under his patronage.

Roger had plans of installing a family vault in the Cathedral of Cefalù. The fantastic porphyry sarcophagi that now decorate the Cathedral of Palermo were originally made for Cefalù. It was Frederick II who had them moved to Palermo to build his own pantheon. He surrounded himself with his admired grandfather Roger II, Roger’s daughter Constance and her husband, his father, Henry VI.

Tankred, 1189-1194. Denarius o. J. From Gorny & Mosch auction sale 221 (2014), 3089.

Roger II was followed by William I the Bad, William the Bad was followed by William the Good. And that was it for the moment. William II remained childless.

Tankred, 1189-1194. Denar o. J. Aus Auktion Gorny & Mosch 221 (2014), 3089.

And so one of Roger’s II grandsons ascended to the throne and a bastard on top of that. His name was Tancred of Lecce. This, in turn, enabled yet another to take part in the dynastic gamble.

Porphyry sarcophagus of Henry VI. Photo: KW.

Henry VI, German Emperor, had married Constance, the daughter of Roger II. He justified his right to Sicily with this connection. And he was successful. Although Henry VI and his rough treatment of his defeated enemies weren’t exactly popular with the people, I highly doubt he spend sleepless nights worrying about it. Sicily took revenge in its own way. The still very young king died of endemic malaria and left behind only an underage son, …

Porphyry sarcophagus of Constance. Photo: KW.

… whose mother Constance was unable to secure the kingdom for him.

Frederick II, 1197-1250. Augustalis, after 1231, Brindisi. From Künker auction sale 239 (2013), 5297.

What follows now has become the material of so many legends and myths that it is almost impossible to get at the naked truth. Frederick II became the greatest king Sicily had ever seen. He secured his rule by weakening the Holy Roman Empire like no emperor had done before him. He was without means and still won the civil war against Otto IV with his charisma and the support of the German princes. His plan succeeded because the princes hoped that Frederick would remain in Sicily and not interfere with the expansion of their own regional territories in the future.

The boy from Apulia radically used his Kingdom Sicily to finance his expansionary policy. Never before had a bureaucracy been run more effectively because the only way for Frederick to pay his military campaigns was by making enough money in taxes. Goal was the even richer north of Italy whose taxes Frederick claimed as well. It probably didn’t bother him much that he antagonised the Pope, but the Papal animosity cost his descendants not only their power, but also their life – as in the case of Conradin.

The crown that Frederick II placed in his wife’s grave. Photo: KW.

There is much to think about when you stand in front of the sarcophagi of all these powerful men and rather less powerful women, who wrote our history.

To the restrooms? Behind the altar! Photo: KW.

If you should feel a more urgent need, you’ll find a place to relieve yourself on the way to the treasure room. Let’s hope that there is more to be discovered behind the altar …

Anyway, we’d seen enough buildings and heard enough stories for one day.

If you want to know who ruled Palermo after the Normans, stay with us for the last episode on our Sicilian journey. We’ve saved some special treats for you. Among them the prison of the Spanish inquisition in Palermo, where paintings on the cell walls bear testimony to the fears, hardships and hopes of the prisoners.