The exhibition Scapegoat at the National Museum Zurich examines collective violence against individuals, from antiquity to the present day. It explores prehistoric human sacrifices, lynching (including burning at the stake) and violence in our times. At the same time, the exhibition looks at the forces that have attempted to oppose violence, such as Judaism, Christianity, and the scientific community during the Enlightenment.

At the 1994 World Cup, favourites Colombia lost to the USA thanks to an own goal by Andrés Escobar, and were knocked out of the tournament. Back home in Colombia, the defender was shot dead for his mistake. In 2007, Englishwoman Fiona Pilkington killed herself and her 18-year-old daughter. For ten years, she had been terrorised by a gang of youths because her daughter was mentally handicapped. Neither the police nor social services had helped the single mother. In Canada, Amanda Todd took her own life in 2012. The young woman was the victim of the circulation of a nude photo on the internet. As a result, she suffered massive cyber-bullying.

Of course, the scapegoat mechanism is not a modern phenomenon. Groups of people have always needed scapegoats: when a community channels its aggression onto a single victim, it strengthens its own cohesion. The history of hate campaigns, lynching, human sacrifice and witch-hunts goes back to prehistoric times. Disasters and crop failures, but also envy and frustration, can lead to violence within a community. Often in such situations, people knowingly or unknowingly single out a victim and project onto that individual the sole responsibility for the crisis. It is usually outsiders or the weak – children, the disabled, strangers, women – who are the targets of this stirring up of hatred.

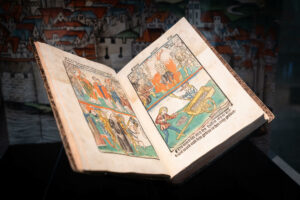

The exhibition traces the subject of the scapegoat through the present time, the modern era and the Middle Ages, antiquity and prehistory. The search for guilty parties was particularly intensive during the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern era.

Inexplicable natural phenomena had to be blamed on someone; to provide reassurance, ‘witches’ would be found guilty. One of the examples looks at the execution of the last ‘witch’ in the Canton of Zurich. Anna Rutschmann, from Wasterkingen in Rafz, was beheaded in 1701. Villagers had gone to the local Landvogt (bailiff) in Eglisau and made accusations against her and seven other people. The accusations related to a number of mysterious illnesses which had afflicted the village. One of these illnesses was severe headache, which we would probably identify today as migraine. The Rutschmanns – seven of the eight people executed were relatives – were held responsible. Why the Rutschmann family? It was probably envy, because the Rutschmanns were among the wealthiest in the village. After repeated torture, they admitted having made a pact with the Devil and were sentenced to death.

The gladiatorial battles in ancient Rome originated from the custom of sacrificing a human being in honour of the deceased. Prisoners of war were forced to fight to the death during the funeral festivities. In times of great need, even the Greeks sacrificed a person to their gods from time to time.

The archaeological finds from a pile-dwelling settlement in southern Germany displayed in the exhibition reveal fragments of the skulls of children. These young people were killed deliberately. This seems to suggest that these, too, are human sacrifices – perhaps to avert an impending flood.

In addition to violence and its channelling onto specific individuals, however, the exhibition also looks at those forces that have opposed violence – forces such as religion, and the natural sciences that flourished with the Enlightenment. And it goes without saying that modern forms of vilification, which have increased massively through the use of the internet and social media, are part of the exhibition.

The exhibition has opened on 15 March and will run until 30 June 2019.

You can find further information on the museum and the exhibition on the website of the National Museum Zurich.

You can learn more about climatic changes leading to economic crises and eventually to social movements and revolutions in two MoneyMuseum films: ‘Change in Climate and the French Revolution’ and ‘Climate change – 1816: The year without a summer’.