September 12, 2013 – After nearly forty-five years, The Royal Mint has revived a coin design by one of the 20th century’s most influential designers that would otherwise have remained under wraps for ever.

Christopher Ironside’s ‘lost’ Royal Arms design for the decimal fifty pence piece. The Royal Mint has revived it to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Christopher Ironside’s birth. This is the new edition.

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of his birth, 50 pence pieces bearing decimal coinage designer Christopher Ironside’s ‘lost’ Royal Arms will enter circulation this year, and are to be minted in collectable precious metal editions.

Ironside’s sketched design submissions for the new decimal 50p.

Ironside’s Royal Arms design lost out in 1969 when the Royal Mint Advisory Committee (RMAC) were tasked with choosing between two designs for the nation’s new decimal fifty pence piece. Finally, they came down on the side of popular opinion and opted for Ironside’s seated figure of Britannia.

The story of how Ironside won, then lost, then again won the challenge to design Britain’s new decimal coin series is fraught with political, artistic and social wrangling. It reveals much about the determination and strength of character of the man who went on to become one of the most successful coin and medal designers of the 20th century.

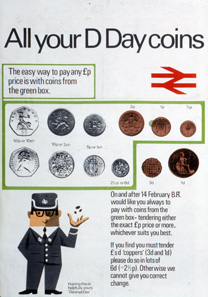

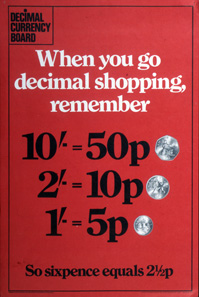

The government informed with posters about the changes.

The enormous task of weaning the public off a familiar currency that was so well loved that its coins were known by nicknames such as ‘bob’ and ‘tanner’ was a tough one, but economically essential for the country. The designs, eventually unveiled in 1968 and 1969, took the best part of a decade to plan.

Graham Dyer, today the Royal Mint Museum’s Senior Research Curator, was a junior executive at The Royal Mint in Tower Hill at the time, and recalls: “It was understood by all that the United Kingdom’s first decimal coin series was an unusually important event for the nation, and so a great deal of time and care went into selecting the designs”.

The RMAC had originally set about finding designers for the new coinage in the early 1960s, in a closed competition veiled in secrecy. Wishing to attract entrants of the highest calibre, the RMAC invited distinguished teams from the Royal Academy, the Royal Institute of British Architects, and a joint team combining the forces of the Royal College of Art and the Royal Designers for Industry to compete in the challenge.

Whilst a team approach was used at the outset, the merits of Royal Academician Arnold Machin and Royal College of Art tutor Christopher Ironside soon brought them to the RMAC’s attention as individuals. Machin won the prestigious task of creating a new portrait of the Queen, and Ironside’s distinctive designs singled him out for selection for the reverses of the new decimal coin series.

Christopher Ironside.

Graham Dyer recalls Ironside as a striking, well-spoken figure, with great physical presence and the ability to transcend boundaries that others could not. “In those days, Sir Jack James, the Deputy Master of The Royal Mint was inaccessible to most people, but Ironside was a regular visitor. He would call round and they would have a drink and a chat – Ironside was very much the man of the moment”.

On D-Day, February 15, 1971, the new coins were introduced.

Then came the blow that nearly ended Ironside’s prospects as the designer of decimal coinage. A change of government from Conservative to Labour in 1964 saw the arrival of James Callaghan in the position of Chancellor of the Exchequer, and therefore Master of the Mint. Agreeing that decimalisation was necessary, but disregarding the work that had been carried out by the RMAC in planning for the change, Callaghan announced that since decimalisation would affect the entire country, it seemed reasonable that everyone within it should have an opportunity to submit designs.

The RMAC, unused to having their advisory powers questioned by politicians on matters of design, were taken aback by the decision, but were obliged to stand Ironside down as winner. Almost a thousand entries were received in a new, public competition, and entries were judged anonymously. Undeterred, Ironside entered the new competition with a mixture of old and new designs, which outshone rival entries once again with their distinctive qualities.

Work on the project resumed, dominating many years of Ironside’s life with numerous trips to and fro as the RMAC requested minor design alterations, in a period later described by his widow Jean Ironside as frustrating for the designer. Early in 1968 Ironside’s designs for the new coins were revealed, representing the crest of England (10p), the thistle of Scotland (5p), the feathers of Wales (2p), the portcullis of Parliament (1p) and a royal crown (1/2p). There were no plans at this stage for a 50p coin because the ten shilling note was still in use.

With leaflets and posters the Government tried to help people understand how to deal with the new currency. And it became a success.

Graham Dyer recalls the country’s reaction: “Initially the designs had a fairly good response from the press, but publicly, regret was expressed about the omission of Britannia from the new coins, as she had been a constant feature of British coinage since 1672. The press fastened onto this and it became a subject of much public discussion”.

Soon afterwards it was decided to replace the old ten-shilling note with a new fifty pence coin (the note was no longer economic because it was of a denomination that saw a lot of use, and therefore wore out quickly). Ironside was asked to submit designs for one new coin to complete the series, and came up with two propositions that set the RMAC a challenge: the figure of Britannia, seated, would undoubtedly meet with public approval, but the Royal Arms was acknowledged as a brilliant design, bringing together all the individual elements of the smaller denomination coins, and therefore thought by the RMAC to be a better fit with the heraldic theme of the series.

Souvernirs remember the historical moment in 1971 when Britain introduced new coins abandoning the traditional ‘Imperial’ currency system.

Popular opinion won, and in 1969 Britannia resumed her reign on Britain’s coins. The highly-regarded Royal Arms design was liked so much by members of The Royal Mint Advisory Committee, however, that trial pieces of the design were made in the hope that one day a use would be found for it. It remained unseen until now, when it has been revived for the 2013 fifty pence, in honour of the centenary of Ironside’s birth. The version of 2013 differs from the original in that it has been reduced to fit the smaller size fifty pence coin, and the word ‘new’ has been replaced by ‘fifty’.

Jean Ironside recalls an article written in 1969 in which her husband said, “The work of a great many artists who are geniuses is never recognised and probably eventually disappears. But if one is a coin designer, one’s work lasts possibly long after death, everyone becomes familiar with it and it forms a small part of the history of the country for which it was designed.”

At the time of decimalisation, Christopher Ironside had taken the decision to omit his initials from the coins, famously uttering the tongue-in-cheek explanation that it would be arrogant to include his initials, but it would be even more arrogant not to! In a nod to Ironside, the 2013 version of the coin includes the initials C.I., a move which Graham Dyer believes would have made the great designer smile. “I think he would be amused and proud to think that we have at long last managed to ensure that his initials are featured on United Kingdom coinage”.

You can find information on the decimalisation on the Royal Mint’s website.

Details about the process of introducing the decimal system and pictures of the old coins offers this website.

In the archives you can find a 1971 film explaining the new decimal currency system.

A neutral review gave the BBC in 2011 on occasion of the 40th anniversary of D-day …

… while the Daily Mail deplored at the same time ‘The day Britain lost its soul: How decimalisation signalled the demise of a proudly independent nation’.