by Ursula Kampmann

November 29, 2012 – Our travels through northern Spain are gradually drawing to a close. Today we’re visiting a few famous sites along the Way of St. James, including the mysterious Eunate. Our first destination, however, is the pantheon of the Kings of Navarre, Najera

Wednesday April 18, 2012

If it’s not a Dutch tour group getting on our nerves, it’s a German one! This group was from the Rhineland and the tour guide was obviously trying very hard to imbue his disinterested package tourists with a bit of knowledge – by reading aloud from the fact sheet that was handed out freely to everyone at the entrance of the Santa María La Real monastery in Najera.

The fortified church of Najera, built directly into the rock. Photo: KW.

The name Najera actually comes from Arabic and means “city between the rocks.” Muslims lived here during the 8th and 9th centuries, a fact that is likely partly reflected in the legend of Roland having fought here against the giant Ferragut by order of Charles the Great. The legend is reminiscent of the story of David and Goliath, and a chronicle from the 12th century actually claims that the Emir of Babylon had sent Ferragut, a descendant of Goliath, to hold the fortress of Najera.

The battle of Roland and Ferragut in Estella at the palace of the Kings of Navarre. Photo: KW.

Ferragut had the strength of 40 men, a nose as long as a hand, and each of his fingers was the length of three normal men’s hands. He had already finished off more than 20 knights before Charles the Great granted his hero Roland permission to fight him. They fought each other during the day and then took truces to rest at night. On the second knight, in an act of courteousness, Roland had placed a stone beneath the giant’s head as a pillow. The giant was so moved by Roland’s gesture that he revealed to him that he was only vulnerable in one spot: his navel. When the two weren’t busy fighting, they had amiable chats on topics such as the Holy Trinity, the Immaculate Conception, and the Resurrection of Christ. On the third day, Roland killed his opponent with a spear to the navel, and Christianity prevailed (or something along those lines).

Sancho IV, 1054-1076. Dinero. From Künker auction 137 (2008), 3485.

Najera was actually first conquered by Sancho I of Navarre in the year 923. The kingdom of Navarre had already existed for a century, but now it rose to become one of the most important powers of Spain and southern France. The denizens of Najera still feel great pride today that the Kingdom of Navarre was also once known as the Empire of Najera.

Sancho III was successful in uniting Navarre and Castille under his rule. A division of the estate followed, however, in which Sancho IV received the Kingdom of Pamplona. The young ruler was murdered, and the kingdom was divided among his brothers. It would only regain independence in 1134, under the leadership of García IV.

Thibaut II, 1253-1270. Denier. From Künker auction 152 (2009), 5191.

The year 1234 marked the death of the last “Spanish” king of Navarre. He was succeeded by his nephew, a son of his sister who had married Thibaut III, the politically prominent Count of Champagne. Consequently, Navarre came under French influence.

Jeanne I, 1274-1305. Denier. From Künker auction 152 (2009), 5192.

When their son Henry I of Navarre died without a son and heir in 1274, he was succeeded by his daughter Johanna, who was just two years old. She therefore proved to be very much in demand on the marriage market and was snapped up by the French king for his heir Philip IV, better known as “the Fair.” From then on, all Capetians were also Kings of Navarre, and it wasn’t until 1328 that Navarre once again managed to break free of France. In the Pyrenees, women had inheritance rights (someone’s sure to crack a joke about the backwardness of mountain people!), but in France they did not. As such, after the death of Charles IV, Navarre had an heir in his niece, Johanna. Her right to the French throne, however, was not recognized.

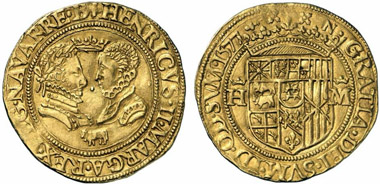

Henry II and his wife Margarete of Navarre. Double ducat of Henry VI from 1577 in honour of his grandparents. From Künker auction 218 (2012), 5149. Photo: KW.

After this, things started to get confusing. There were rival aristocratic parties, a civil war and a division and, in 1515, the southern part of Navarre went to Ferdinand of Aragon, who, through his marriage to Isabella of Castille-León, was to unify Spain. The northern portion that lay beyond the Pyrenees was merged into the Kingdom of France. Or maybe it makes more sense to say that France became merged into Navarre? In any case, Henry III of France was succeeded by Henry II of Navarre, who then became Henry IV, and, after converting to Catholicism, settled in the capital city of Paris. After all “Paris is well worth a Mass …”

Najera’s tremendous picture of the Madonna in the rock grotto. Photo: KW.

Najera had been the residence of the Kings of Navarre until 1076. The Santa Maria La Real monastery was founded in 1052, and not surprisingly, it too has a wonderful legend to go along with it. King García III was apparently on a falcon hunt when, suddenly, the prized bird disappeared into a stone cave. There, the king found the falcon peacefully united with the also just hunted dove, sitting under the image of the Virgin Mary, which is now the centre of the tomb.

The tomb of the Kings of Navarre. Photo: KW.

In actual fact, the founding of the monastery was far more political. The “Orden de la Terraza”– the earliest order of knights, which had been created as part of the Spanish Reconquista – settled here, populated by the Cluny Monastery. From here, Cluniac reform spread throughout Spain, driving out the Mozarabic rite that had been prevalent up until then.

By 1889, the monastery and its royal pantheon had already been declared a national heritage site.

The sarcophagus of the doña Sancha. Photo: KW.

The most significant work of art may very well be the Romanesque sarcophagus of the doña Sancha, who died in 1156 during childbirth. Her son, Alfonso VIII, was to make history with his incredible victory over the Almohads at las Navas de Tolosa.

The latticework in the cloister. Photo: KW.

Almost as attractive as the sarcophagus are the lattices in the cloister, which, although all differently designed, all display the same degree of imagination and expertise.

The palace of the Kings of Navarre in Estella. Photo: KW.

About 80 km further east along the Way of St. James is Estella, which was a popular rest station for pilgrims during the Middle Ages. In fact, a quote from a pilgrimage guide from the 13th century serves as the perfect advertisement: “From there (one reaches) Estella, which (offers) good bread, the best wine, meat and fish are abundant, and which is replete with all sorts of happiness.”

So much praise though is cause for caution. In fact, the city was expressly founded in 1090 for the purposes of getting in on the rich, thriving pilgrim business. An icon and an impressive celestial sign, after which the city was named, merely emphasized the overall underlying aim. Estella was endowed with rich privileges and became a boomtown.

Entrance to San Pietro de la Rua. Photo: KW.

The next coup was scored in 1270. It came about in the form of another celestial sign: a star twinkled upon the grave of an anonymous pilgrim and, wonder of wonders, in it they found the Bishop of Patras, equipped with all the required documents to attest to his identity. Even more impressive was the fact that the anonymous traveling bishop also had a couple of relics of the Apostle Andrew in his bag, who had ultimately sustained martyrdom in Patras in the year 62.

The relics were immediately annexed for the main church, San Pietro de la Rua, and business thrived. By 1354, there were six pilgrim hostels in Estella! Pamplona, in comparison, was like a backwater. Burgos proved a more apt comparison.

The demise of the Way of St. James, however, also spelled the end of Estella’s importance.

A church – no idea which one, but it was closed, in any case. Photo: KW.

By now, the city was starting to feel abandoned. It was 2:00 pm and all the Spaniards had retired for siesta. All the churches were closed and the sky was overcast. There really wasn’t much else for us to do but go eat. Even then, we didn’t manage to draw out the meal quite long enough.

The queen’s bridge – Puenta la Reina. Photo: KW.

As a result, in Puenta la Reina, we only got to have a look at the famous bridge. It’s not clear exactly which queen built this bridge – the details seem to have gone astray over the course of the centuries. But regardless, today the site is considered to be the actual start of the “Camino Francés” toward Santiago, or the “Franzosenweg,” as it was known in the Middle Ages. It wasn’t used just by the French, of course, but rather by anyone who had come by foot over the Pyrenees. As such, the preferred, more politically correct name in present-day Spain is “Camino de Santiago.”

Still an unsolved mystery: Eunate. Photo: KW.

Not far from here lies the small Chapel of Eunate, which still tends to be described in relevant literature as an enigma and place of special spiritual power.

In actual fact, the small, octagonal chapel lies fairly secluded (or, rather, “lay” secluded, since today Eunate is a very popular tour group stop) in the countryside. Similarly octagonal arches also surround the whole building. Little is known about the origins of the structure, which obviously leaves much room for fantastical theorizing and added mystique. The earliest source for the church dates back to the year 1487, by which time the Way of St. James had long lost its great importance.

Consequently, great stories were invented about the place, about the Templars having recreated here a replica of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. In reality, however, there’s much to suggest that it wasn’t in fact the Templars, but rather the Knights of St. John who had a hospital here. There’s a document that refers to this region, although it doesn’t explicitly mention Eunate. In any case, archaeologists have discovered numerous pilgrim graves in the area around Eunate, which would seem to make a fairly convincing case for the existence of a hospital.

Sos del Rey Católico – in the middle of the mountains. Photo: KW.

And with that, we called it a day. We drove to our parador, Sos del Rey Católico. To this day, I still haven’t been able to figure out what the word “sos” means.

Sadly, we’re almost at the end of our journey. There’s just one more leg of our travels to report on – the next episode of our numismatic journey through northern Spain takes us to Pamplona, which was made famous by Ernest Hemingway.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.