by Ursula Kampmann

August 2, 2012 – The second leg of our tour through Northern Spain took us to the region that gave us the Reconquista, through the difficult terrain of the plateau and high mountain regions. Forget everything you thought you knew about Spain, and join us as we make our way to Cangas de Onís.

Saturday April 7, 2012

That morning we woke to find the skies gray and cloudy. It was raining as we put the luggage into the car and by the time we reached the highway it had begun to pour. The downpour didn’t let up throughout the entire trip. Our guidebook may have raved about this being one of Spain’s most beautiful stretches of highway between the wild coast and the high mountains, but sadly our view extended at most 50 meters. Beyond this, the rest of the world was engulfed in gray.

The Parador of Cangas de Onís, in Foreground, the Swollen River. Photo: KW.

The weather made it rather unappealing to actually make our planned stop at Altamira. In any case, you can’t actually visit the original cave. Visitors are led through the exact same reconstruction that I’ve already seen several times in the Deutsches Museum in Munich. So, instead, we continued along the wet highway. And by the time we arrived in Cangas de Onís, the rain had finally let up somewhat and the imposing gray cloud cover had thankfully broken up.

The First Soldier of the Reconquista: Pelayo. Photo: KW.

Just a few steep mountain road kilometres away is the site said to have been where the Reconquista started – at least if we choose to subscribe to later historians’ accounts:

The man responsible is said to have been called Pelagius, Pelayo in Spanish, a young man from the Visigoth elite who managed to escape the military disaster against the Arabs in the Battle of Rio Guadalete in July of the year 711.

Spain, Umayyad. Fals, prior to 755. From Künker Auction 137 (2008), 3378.

Pelayo went to Asturias where he entered into the service of the Muslim governor, Munuza, who at that time had his residence either in Gijon on the coast, or in Leon in the interior. What follows is a cock-and-bull story that is all too familiar to us from different contexts: Pelayo had a beautiful sister with whom the governor fell in love. Her brother obviously didn’t want her marrying a man of another faith. Munuza, however, was resourceful – he issued an order to remove the brother from his court and then took the young woman as his wife. Upon his return, Pelayo is said to have been so infuriated that he planned a rebellion.

He gathered his followers in the valley of the Sella River, the very same river that flows past our parador. The Sella has tunneled a serpentine like passage through the mountains, making the area quite confusing to navigate. Pelayo would have had ample opportunity to hide himself and his men or to lie in ambush.

The Cave in Covadonga, Today a Popular Day-Trip Destination. Photo: KW.

There’s no record, of course, as to just how Pelayo and his scant troop of followers managed to defeat Munuza’s troops. But the Spanish account still recognizes the intervention of Virgin Mary for the benefit of the future Spain. In a cave now known as Covadonga – from cova dominica, ‘Cavern of the Lady’ – Pelayo received a sign. Two angels brought him a cross and announced that with this sign, he would be victorious. (Any similarity to public figures or characters living or dead was, of course, fully intentional.)

In 722, Pelayo was indeed victorious. If we choose to believe the chronicle prepared under Alphonso III of Asturias, (866-910), 187,000 Muslims were killed there. Sources from the other side likewise tell of around 300 rebels who had entrenched themselves at Covadonga. According to the tales from this side, these rebels were decimated by the brave Islamic soldiers, with the exception of just 30 survivors. After having done so, the Muslims preferred to retreat to the considerably more comfortable imperial capital. Whatever happened, it was enough to earn Covadonga its place in Spanish history.

The Chapel with a Lone Voice in the Wilderness. Photo: KW.

What really happened? Sadly, nobody can reconstruct the series of events. But at any rate, today Covadonga is a national Marian shrine to which Spaniards regularly make pilgrimage. The cave where Pelayo had his vision is way above the street. They’ve incorporated a small chapel in which a mass was being held when we arrived. The poor priest – you had to feel sorry for him, the way he was desperately trying to quiet down the teeming stream of pilgrims. He was screaming his head off, an act that the microphone only served to amplify. It wasn’t exactly conducive to a tranquil chapel atmosphere!

The tombs of Pelayo, his sister (as she must have fled the Muslim governor’s harem?), his wife and his son-in-law Alphonso I, the Catholic, are all also supposed to be here, but the hubbub meant that unfortunately we weren’t able to find them.

The Neo-Gothic Church Above Covadonga. Photo: KW.

Somewhat further up is a church that, in the 19th century, was considered appropriate for the big event. It wasn’t exactly an artistic delight, but the site itself was impressive enough (if one can imagine it without tour buses, restaurants, cars and souvenir stands). It’s certainly possible to imagine a small army having entrenched itself here and made a stand against a larger troop that really wasn’t interested in squandering too many men. Anyhow, the governors of Al-Andalus were planning the conquest of southwestern France at the time. In 721, a campaign had been conducted across the Pyrenees, and in 722 the plan came about to conquer the Frankish Empire. A small, insignificant troop was to quietly barricade themselves in Asturias. They’d worry about them later.

This ‘later’ never came, however, after Charles Martel stopped the Arab troops in the year 732. At any rate, the invasion of France gave Pelayo and his men time to establish themselves as successors to the Visigoths.

The Abbey of Villanueva. Photo: KW.

Our parador offered a continuation of the story. Pelayo’s son-in-law, Alphonso I of Asturias, named ‘the Catholic’, built the church of San Pedro de Villanueva here in honour of his late predecessor, the son and heir of Pelayo, Favila.

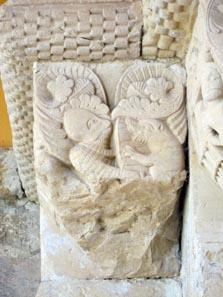

Favila Bids Farewell to his Wife as he Goes Hunting. Photo: KW.

Favila ruled for only two years, which wasn’t really sufficient to make him celebrated for his actions.

Favila Battles the Bears. Photo: KW.

To this day, however, it is known how Favila died. It was a hunting accident – a bear, which are said to still exist in the bordering national park, made the hunter the hunted.

Idyllic Countryside. Photo: KW.

We used the last (and amazingly still rain-free!) hours of the day to take a delightful walk. The pastoral surroundings were idyllic, with cows grazing in the pasture …

The Characteristic Granaries of Asturias. Photo: KW.

… and the characteristic granaries of Asturias, which rest on tall stone columns to prevent mice from getting in and helping themselves to a little snack from the gathered stores.

The Granaries Found their Way into the 21st Century. Photo: KW.

Many of the granaries are still standing, and not just at the tourist sites. They actually managed to find a new purpose: the clever Asturian uses his granary as a covered, well-ventilated open-air garage!

Easter Sunday, April 8, 2012

We woke up to find it sunny! Our long-awaited vacation weather had finally caught up with us. Feeling light and cheerful, we made our way to Oviedo, the third capital of Asturias founded by Alphonso II the Chaste. I can’t show you any coins from him, however; The Asturias of the 9th century was still a bit too preoccupied with more important things than coinage.

Oviedo’s Coat of Arms: Two Angels Bringing the Holy Cross. Photo: KW.

After the victory at Covadonga in the year 722, Pelayo, the first Asturian king, established himself in Cangas de Onís. His grandchildren extended the empire so far that a new, more central capital became necessary, which was located in the considerably further west lying Pravia, although only for a few years. Alphonso II (791-842) bunked in in Oviedo and took the treasures of the empire with him, including the famous cross that appeared to Pelayo on the occasion of the Battle of Covadonga. It’s still preserved today in the Holy Chamber of Oviedo (Cámara Santa in Spanish).

The Cathedral of Oviedo with the Cámara Santa. Photo: KW.

It was Easter Sunday, so naturally the church was being used for much more important things than a place for curious tourists to poke their heads into. The Cámara Santa was closed, which was understandable but still disappointing. We took comfort in the fact that we wouldn’t have gotten to see the original Cámara Santa or the real cross one way or the other.

Why not? Because in 1934, there were rumblings of the impending Spanish Civil War. In 1931, the second republic had been declared. It had to contend with the sharp extremes between the left and the right. When a middle-right coalition came to power after the 1933 election, a number of communist-influenced uprisings followed. As the heavily industrialized Asturias already had a labour movement, railroad workers and miners came together and joined forces into a revolt. The destruction of the venerable relics of Nationalist Spain in the Cámara Santa was a rousing beacon to the rebels. Only a few stones were left, which Franco had used in the rebuilding between 1938 and 1942 in an attempt to retain at least a trace of authenticity.

The angel cross was stolen and smashed to bits in 1977 (there was quite possibly a better chance of selling the famed relic in fragments). The remnants were found again in 1985 and restored.

Flea Market. Photo: KW.

There was nothing else left for us to do in Oviedo, other than to saunter through town on a stroll that took us directly to a flea market. The numismatic pickings were, suffice it to say, rather scant.

The Newly Built Oviedo Museum – An Absolute Must! Photo: KW.

The museum was the only thing open on this Easter Sunday. We actually hadn’t wanted to go in at all, seeing as it was the first day of our vacation that it wasn’t raining, but at some point we agreed to have a look.

Ivory Carving of an Auroch from the Magdalanian. Photo: KW.

We didn’t regret our decision for a second! The stuff was amazing and terrifically presented. The exhibition began with the Paleolithic. It turns out that Asturias has been inhabited for a mind-boggling 300,000 years! While people in Schaffhausen are proud of the odd rendering of a reindeer (the original of which isn’t in Schaffhausen, incidentally, because it was considered to be a fake upon its discovery and wasn’t purchased), here there were several display cases full of bones where you could see mammoths, aurochs and wild horses. The amazing cave paintings could have been brought in so badly, but a multimedia exhibition showed just how many unknown caves there are in this land. We were completely stunned and resolved that at some point we would have to take a much closer look at the region around Altamira, which, only yesterday, had seemed so unappealing.

Hoard of Standardized Axes. Photo: KW.

Dolmen were built in Asturias during the Neolithic Period. The region must have been exceptionally rich, as evidenced by the discovery of numerous deposits of copper and bronze axes. The material may have come from the area itself: Some of the oldest underground mines were located in Asturias, and copper was mined in them.

Model of a Hilltop Settlement. Photo: KW.

Like many other regions of Europe, the form of settlement began to change as of the 7th century BC. Hilltop castles emerged, like the Heuneburg hilltop fort that is quite well known in Germany.

Gold Mining. Photo: KW.

The Romans came next. They’d been conquering Spain piece by piece since the war against Hannibal because of the precious metals. Most of the Roman aurei of the imperial period, in fact, were likely made from the huge gold deposits found in Asturias.

The Hoard of Cenero (Gijón). Photo: KW.

It’s a matter of pride that a large number of coins found their way into the museum, including the hoard of Cenero, which consists of 166 bronze coins from the 1st and 2nd centuries.

The Hoard of Penaturmil. Photo: KW.

Also on show, a medieval hoard from Penaturmil, concealed in a small bronze pot.

We were absolutely thrilled by the museum, and when I subsequently tried, in a rather unique mixture of Spanish and Italian, to convey to the woman at the front desk that I desperately wanted to buy a museum guide, she proceeded to gather up every single scientific publication she had. She piled the whole mass on the desk and then asked if that might be what I had in mind. Of course, it was! She pushed the pile of books over to me. If I understood her correctly, these valuables were unsaleable anyway and designated for pulp sooner or later. I was so stunned, I didn’t even know how to thank her for the amazingly kind gesture. But I’m sure you can imagine how completely thrilled I was by her generosity.

Easter Sunday Procession. Photo: KW.

As we left the museum heavily laden with my new acquisitions, we ended up right in the middle of the Easter procession. Yes, it’s true – in these parts there’s not just a procession on Good Friday, but on Easter Sunday too. The priests in their red high feast day vestments leading the way, followed by young boys and girls in black and red with tall candles. Four burly men with somewhat dusty looking plumed hats carried the float on which, in the middle of a floral arrangement, the Risen Christ hovered over the crowd. A brass band played some accompanying festive music and a crowd lined the sides of the road hoping to catch a glimpse.

The Roman Bridge of Cangas de Onís. Photo: KW.

Since the day was still young, despite our museum visit, we decided to take advantage of the lovely weather and explore the region a bit more. We drove to Cangas de Onís, whose bridge over the raging waters of the Sella is said to date back to Roman times.

Cangas was completely full of Easter daytrippers who had taken up residence in the cafés. We were also quite hungry and would have been quite happy to grab a bite, but we’d arrived too late – every cake counter was completely empty. There was literally nothing left, except maybe a few extended shelf life baked goods. Stomachs empty, we instead sought salvation in the rich culture, and visited the area’s great sight of interest, Santa Cruz (named after the angel’s cross).

The New Construction of Santa Cruz. Photo: KW.

The original church was built by Favila in 737. This detail is relayed by a contemporary inscription built into the modern church. It’s considered to be the oldest written testimony of the Reconquista, which is perfectly lovely and all, but not particularly mind-blowing. Santa Cruz does, however, offer a very special surprise – back then, Favila was looking for a prominent, eye-catching location for his church, which he managed to find on a small hill on the far side of his capital city. He didn’t think to question why there was a hill on this spot.

A Look Through the Church Floor. Photo: KW.

When during the Baroque Period, however, a Spanish king gave the order to excavate to see if the historical lore was true that the earliest kings of Asturias had their graves here, it was established with quite a bit of excitement that this tradition was, apparently, true. A dolmen was discovered, which, being from the Neolithic Period about 4000 years ago, was actually too old to have served as a tomb for the Asturian kings. But such petty archaeological details weren’t of much concern during the Baroque Period. A magnificent church was built in 1632 and then completely destroyed in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War. The current new construction dates back to around 1950.

It had now officially been an overly full day, so we went back to the parador.

The next leg of our journey will bring us to Picos de Europa and then to Lugo, which boasts the best-preserved Roman city wall anywhere in the world. Join us on the 2.13 km-long walk along the top of the wall.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.