by Ursula Kampmann

July 28, 2011 – What is there to be found in Pherai, the city where once upon a time such beautiful coins were produced, like the ones that reached record prices in Zurich only recently? Does reality match up with the coins’ testimony? But first a trip to Mount Olympus.

Day 13, June 22, 2011, Drive to Mount Olympus

Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as “the Olympus”. It is a mountain massif of approximately 40 km length and 30 km width with more than 10 individual peaks with heights from 2700 to 2900 m. It is a popular destination with winter holiday makers. During summertime, one looks for peace and cool air.

On Mount Olympus. Photograph: KW.

Whereas many ramblers take the difficult way to get from Litochoro through the chasm of Vitos to Prionia, the modern tourist may decide to take the easier option, i.e. driving by car on a fully constructed street trough the National Park.

Parking site of Prionia. Photograph: KW.

Destination is the well-attended parking site of Prionia where cars from almost every nation can be found. No wonder, then, that there is a tavern near-by.

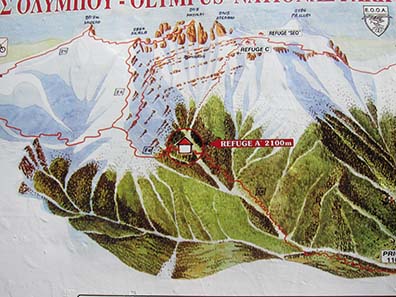

Mount Olympus massif. Photograph: KW.

Many rambling trails start from here. Most visitors, however, settle for refreshments on the tavern’s terrace so that with only a few steps away peace, solitude and the Mediterranean flora and fauna can be enjoyed.

Lizard sun-bathing. Photograph: KW.

My favorites are the many, many lizards living here in every size and shape possible. Ranging from a few centimeters length to almost half a meter, from brown via brown-green to emerald-green, from timid via trusting to almost bold.

A question for biologists: what is this? Photograph: KW.

I don’t want to forget the many different butterflies one hardly comes across anymore in Germany. We noticed quite a number of white weaves in the pines. Unfortunately, so far we haven’t found any solution as to what might be. Hence, if there is anyone familiar with tree varmints, I’d appreciate any hint.

Testimonies for the cult of Zeus Olympios on Mount Olympus. Photograph: KW.

By the way, in antiquity, Mount Olympus as the gods’ place of residence was no taboo. Again and again, humans had climbed it. That is testified by archaeological finds discovered on Agios Antonios peak, at an altitude of 2.817 m.

Logo of the National Park of Mount Olympus. Photograph: KW.

Of course, the National Park draws on the impressive depiction of Zeus on the reverse of the tetradrachms of Alexander the Great. But only the gods know why, of all tetradrachms, one from Memphis in Egypt was chosen for that purpose.

Highlight of a trip to Mount Olympus: a visit to Gastrodromio. Photograph: KW.

Anyone who wants to dine at the foot of Mount Olympus with a gorgeous view is recommended to Gastrodromio in Litochoro. Here, fine Greek cuisine with high culinary claims is cultivated. The menu is manageable, everything is freshly prepared. Only the wine list is so ample that perusing would take some time. Anyone looking for more information on Gastriodromo please click here.

Beginning of environment protection in Greek daily-life. Photograph: KW.

This is a good occasion to mention briefly how, in the whole of Northern Greece, protection of environment in daily-life is preached. Back in Ioannina, we already noticed big, centrally situated collecting points for discarded metal and glass. Even in the tiniest village container for recyclable material can be found. In addition, Greek news explains in detail why and how these facilities are to be used.

Day 14, June 23, 2011, Pherai and Pharsalos: somewhere in Thessaly

Having visited mainly Northern Macedonia with Platamon as base camp until now, today’s destination is Southern Thessaly.

Pherai (Thessaly). Alexander, tyrant 369-358. Head of Ennodia en face. Rev. Alexander riding r. From BCD Coll., auction Nomos AG 4 (2011), 1309

This coin triggered Pherai becoming our destination, and for very personal reasons at that. No, of course I didn’t buy the specimen, but it is the most expensive I have ever catalogued in my youth (that was in 1989 for Giessener Münzhandlung).

Pherai – or Velestino, as it is called today – fills one and a half page in ‘Lauffers Lexikon der historischen Stätten Griechenlands’ (Lauffer’s Lexicon of Historic Sites in Greece). It plays a vital role in ancient mythology. The son of Pheres, Admetos, participated in the Calydonian boar hunt and the Argonautica. Off Troy, likewise ships from Pherai were present.

At the end of the 5th cent., the city under the leadership of tyrants became leading power in Thessaly. Lykophron defeated the Thessalians in 404; his successor Jason united Thessaly under the rule of Pherais; Alexander, finally, had to surrender to the Macedonians.

Philipp was proud of this victory. He took a secondary wife from Pherai who bore him a daughter called Thessalonike who gave her name to present-day Thessaloniki.

In Roman times Pherai remained somewhat important: the first strategos of the newly founded Thessalian Federation came from Pherai!

Hence, we were anxious to see the remains of Pherai. Lauffer’s Lexicon tells of a rich source, “Hypereia, widely known in antiquity”, remains of an Archaic wall, foundations of a temple of Herakles, a guesthouse where the Peace of Philokrates was concluded in 346, and a temple of Zeus.

Hypereian Source of Pindar. Photograph: KW.

Brown signposts indicating archaeological excavations let our expectations rise. The first disappointment, however, awaited us in the village’s center. Where the Hypereian Source of Pindar bubbled once, there is garbage today. The concrete surrounds – like so much in Greece – are smeared with graffiti.

Temple of Zeus Thaulios. Photograph: KW.

The excavation site of Zeus Thaulios, in contrast, was well-redecorated. There was no parking site, but at least a paved way – at the expense of the EU – round the ruins.

Part of a city wall. Photograph: KW.

By car we drove through the village to find the other remains. The most frightening sight was the juxtaposition of corrugated sheet shacks which may well live up to the ones of a South- American favela, and the modern Greek functional buildings in elegant pastel shades. There was garbage not only in the spring but everywhere. Once we found a part of the city wall – made accessible by a paved way the EU paid for – we couldn’t stay long. It stank appallingly of dung and feces.

The constructed acropolis of Pherai, a farmyard to the left. Photograph: KW.

A (very clean) Christian sanctuary on the opposite hill provided the best view at the constructed acropolis. That was where we stood, alternately looking at the ancient wall and the modern farmyard made of corrugated sheet and pallet wood.

Unkown foundation remains from ancient times. Photograph: KW.

Although we came across a number of ancient remains in the village, famous Pherai definitely was completely gone. The few remains testified not to former greatness but to present-day decay. In Velestino, we have found no pride of the ancient heritage.

After that disappointment we drove on to Pharsalos, where the king of the Myrmidons, Peleus, father of Achilles, once resided. The well-constructed road took us through a rather undulating landscape. We drove like one usually drives, not too fast for a change… Nevertheless, a police patrol made us stop. Great excitement! Identification cards! We had. Driver’s licence! Handed over. Car papers! Provided. Where we stayed? Huh? Well, our place of accomodation. Well, Platamon. Where we were heading? Er, to Pharsalos. Where we had just been? In Pherai, of course. Okay, we were allowed to drive on and were wished a nice vacation! For hours we kept on puzzling what that was all about. Does Thessaly see so few tourists that the police have to stop them?

Pharsalos (Thessaly). Drachm, signed by Telephantos, late 5th to middle of 4th cent. B. C. Head of Athena r. Rev. Thessalian rider, flinging the lagobolon. From BCD Collection, auction Nomos AG 4 (2011), 1288.

Pharsalos was mentioned for the first time in the context of the First Sacred War about Delphi at the beginning of the 6th cent. Together with Larisa and Pherai, it was one of the most important cities of Thessaly and hold hegemony over Thessaly for a short period of time during the second half of the 5th cent. Those fond of ancient history know Pharsalos as historically highly significant place where the battle between Cesar and Pompey on June 28, 48 B. C., took place. The exact location of the battlefield hasn’t been ascertained so far.

Modern Pharsalos. Photograph: KW.

To put it in a nutshell, the search for ancient Pharsalos failed miserably. Admittedly, a brown signpost indicated the way to the acropolis. After a short walking tour uphill in blistering Friday afternoon, we found nothing except the place where the male village youth showed attention to the female village youth at night (as might be inferred from the several condoms lying on the ground).

View at modern Pharsalos from the place where allegedly the acropolis is situated somewhere. Photograph: KW.

At least, Pharsalos is a comfortable, well-kept place. Houses are new, there are flowerpots everywhere. We were instantly recognized as strangers, and quite a number of elderly ladies wearing black clothes happened to have something to do on their balconies all of a sudden. We bid them the time of the day, and they did the same. Instead of teeth, we were presented with with loveable smiles. One rather gives a stranger a smile than hide the most adorable false teeth behind a pokerface!

For hours we kept on discussing why that day had been such big a failure. We should have anticipated that a place an ordinary guidebook doesn’t mention isn’t worth visiting. Why, then, did we look for testimonies of Pherai’s former greatness after all?

And suddenly we realized that we experienced just the same as thousands of pilgrims in late medieval times. With a backpack full of notions of the Holy Land they had gone across the sea. Instead of the idyllic place they knew from altar pictures at home, they saw blistering, burnt country, and a population doing good business with the pious pilgrims. Back home, they had felt blessed because they took on the arduous voyage to the Holy Land. Once there, however, one became but one of many in a daily routine that had nothing to do with divine Jerusalem.

We experienced something similar. Just like many coin collectors, we have an almost religious relationship with antiquity. We construct our noble notion, shaped by the most beautiful depictions on ancient coins we regard as reflection of the true and ultimate Greece. Of course, reality can’t keep up with that. Once we – like the pilgrims back then – are confronted with it, we are taken aback. We notice indifference, neglect, wheeling and dealing – and forget that the Greeks deal with their relics every day. What we consider precious, to them it is a part of their environment, at best something profitable (then it gets protection). Only some can afford, like we do, to freely invest time and money in order to see what is left of famous Greece.

Day 15, June 24, 2011, Through Vale of Tempe to Trikala

I have to admit that antiquity was on the fringes today. Our destination was Meteora Monasteries and, most of all, their icons – there were, however, enough ancient relics by the wayside.

Vale of Tempe. Photograph: KW.

Like Vale of Tempe, a small passage between the massif of Mount Olympus and Mount Ossa. This bottleneck was of strategic importance already in antiquity. Xerxes allegedly decided in 480 not to take his chance in a battle with the Greek troops but to circumvent the bottleneck. Herodotus saved the honor of Macedonian King Alexander I when he reported that the monarch himself had warned the Greeks against the scheme of the Persian king.

Spring of Daphne. Photograph: KW.

It is quite an idyllic location even though the convoy of vehicles going from Thessaloniki to Athens is riding only a few kilometers away. Thus Vale of Tempe is renowned for its crashes. The most severe accident so far happened in 2003: an entire school class died when its bus hit a truck.

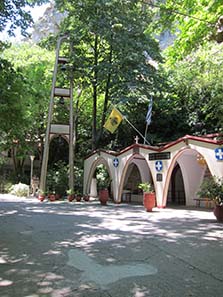

Sanctuary of Saint Paraskevi. Photograph: KW.)

Today, the main attraction to many, mainly Greek, tourists is the sanctuary of St. Paraskevi. She is Apollo’s successor who had a well-known temple at the Eastern end of the Vale. Legend has it that it was here where Apollo purified himself after slaying Python who had ruled Delphi before him. He fell in love with the nymph Daphne who evaded his approaches by turning into a laurel tree. In remembrance of that, a procession moved to Vale of Tempe once every eight years to ritually simulate the cleansing and to cut laurel for the sanctuary.

Souvenir stands. Photograph: KW.

Anyone with a sense of the abstruse will appreciate the Vale of Tempe souvenir stands. The most horrible icons are available for purchase here (of course not painted but only plastered), children’s dreams in pink and light blue, the kitschiest ceramics and much more of that stuff that can be found everywhere in the world where too many tourists stroll around.

The city coat of arms of Larisa is closely linked to the coins. Photograph: KW.

The distance between Platamon and Larisa, through Vale of Tempe, is roughly 60 kilometers. Despite that, it is much more expensive to drive on the highway between these two places than the far, newly constructed route from Ioannina to Veria. The reason defies explanation. You see, the fee system is totally different from the ones we know from France or Italy. There, one usually gets a ticket stating the location where one had joined the highway. Upon leaving the highway it is calculated how much one has to pay for the kilometers traveled. So far, so easily understood. By contrast, Greece has set up toll stations at (very) irregular intervals where the small sum of 1 to 3 Euros has to be paid, regardless whether one has joined the highway only 100 meters ago or has driven 200 kilometers already. Local people know the spots and leave the highway shortly before. (The on-ramp after the control is likewise quite busy.) In Southern Macedonia and Thessaly there is a denser net of control stations, perhaps due to yield being greater there than in the solitude of the new highways. By the way, we only passed through Larisa. We were tired of the day before and didn’t want to be standing in front of a tiny excavation site.

Trikka (Thessaly). Hemidrachm, c. 480-400. Man taming a bull r. Rev. horse protome. From auction Gorny & Mosch 165 (2008), 1243.

In Trikala, ancient Trikka, however, we stopped. In antiquity, it was renowned not only for its cult of Asklepios but mainly for its horse breeding. Phidias is said to have selected the models for his Parthenon frieze amongst the local horses.

Mosque of Sinan. Photograph: KW.

We didn’t visit the Asklepieion (mainly because, when passing through, we didn’t find any hint as to its location). We considered a very special mosque more worth seeing anyway. Sinan, most famous architect of the Ottomans, is said to have built it.

Complex of the Mosque of Sinan, ancient remains in the foreground. Photograph: KW.

Sinan lived in the 16th century. Honorific titles like “Ottoman Michelangelo” reflect his influence on Turkish architecture. Through devshirme, Sinan came to the Janissaries and participated in many campaigns to Central Europe where he came into contact with the ostentatious buildings of the Christians. Under him the art of constructing mosques reached its peak with his impressive buildings being vaulted by a huge, seemingly pending cupola. Selimiye Mosque in Edirna is considered his masterpiece. (The much better known Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, by contrast, is regarded his “mere” journeyman’s piece.

Our example has a brick cupola with a diameter of 25 meters. Unfortunately, we didn’t take it in – we were too late, the building which houses an exhibition room today, was already closed. Thus, we marveled at it and the spoiling graffiti from the outside only.

That will do it for today. The next issue of the Numismatic diary takes us to Pydna and Thessaloniki, one if not the highlight of our journey. There, we experienced the “hot” stage of the protests against the austerity package of the Greek government. Don’t worry, we weren’t harmed. The events on Syntagma Square in Athens have nothing to do with the rest of Greece.

You can read all other parts of this diary here.