by Annika Backe

translated by Christina Schlögl

June 29, 2017 – Google generates “roughly 1,020,000 hits” when entering the search term “money laundering”. While most hits concern the implanting of illegally generated or evaded money, one subject protrudes: Laundering banknotes in the U.S. Treasury Department.

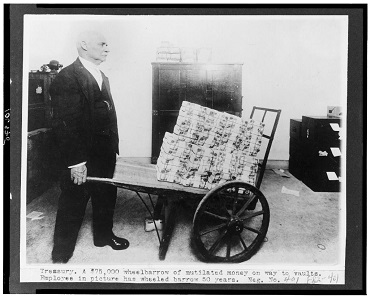

Employee with a wheelbarrow full of banknotes to be laundered, taken between 1909 and 1925. Photo: Library of Congress, Prints &Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-106975).

This highest Treasury Department is responsible for the charging, administration and spending of the public earnings. The release of the official currency is also a task of the institution, founded in 1789, which has its main office in Washington D.C. Shortly after the beginning of the 20th century though, the authority was deeply troubled when they noticed that the released dollar-notes did not last longer than a year due to the exertions of circulation. They started to look for a solution.

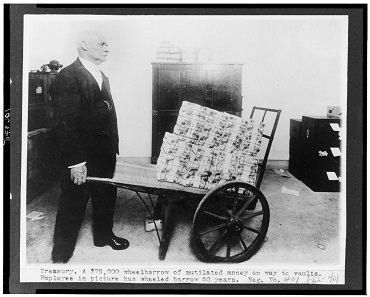

Machine for the laundering of money in the American Treasury Department, photo taken in 1912. Photo: copyright Scherer / Library of Congress, Prints &Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-90450).

They found it in the form of a machine, developed in the span of three years by a resourceful employee. It could be used to clean the circulating banknotes and iron them. The newly “pepped up” notes were then reentered into circulation.

In 1912, a book called “Popular Mechanics” (which would most accurately translate to “Mechanics for dummies” nowadays) explained the procedure of the apparatus to the broad public: “The bills, fed to the machine by a young woman operator, are carried between two 10-in. tapes into a tank of boiling water, and then through a solution which, when heated to the boiling point, forms peroxide of hydrogen. This destroys the germs that may have collected on the bills while in circulation. The bills pass from the disinfecting tank to a rinsing tank, and thence to a pair of large gas-heated cylinders, the passage between which smoothes out all wrinkles.”

According to the description, one banknote would pass through the machine in 2.5 minutes, and the machine could wash and iron up to 35,000 bills on a workday. The banknotes would not be damaged since they consisted of a cotton-linen-blend that would neither dissolve in heat, nor in water. The Treasury Department could thus salvage about 60% of the bills with this method; the remaining 40% had simply suffered too much during circulation. As this procedure allowed the American State to produce less new banknotes, the state saved several hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The printers however distrusted the machines, since they feared for their livelihood. And employees in the offices of the Department would complain about the increased noise distraction in the building. Incidentally, no one in the U.S. Treasury Department has been able to reconstruct in which basement room the machine was located. Reasonable hints are more than welcome.

You can find the website of the U.S. Treasury Department here.

There is a complete explanation of the machine in “Popular Mechanics” from 1912 on Google Books.

Find out which hotel will not only let you spend the night but also launder your change in this article of CoinsWeekly.

And you will find more detailed information on the current cleaning of banknotes here and here.