July 31, 2014 – Until April 19, 2015 the new temporary exhibition offered by the Winterthur Coin Cabinet presents some 60 objects combining an outstanding Swiss private collection with in-house exhibits.

Matteo de’ Pasti (c.1420-1467/68), medal of 1446 on behalf of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Master of Rimini (1432-1468). Copyright: Münzkabinett der Stadt Winterthur, Photograph: Lübke & Wiedemann, Stuttgart.

On display are creations by the leading medal artists of the Italian Renaissance, including Pisanello, Fiorentino, Matteo de’ Pasti, Sperandio, Lysippus and Giovanni Boldù. In addition to eye-catching portraits, there are also figures derived from antiquity and mythological scenes, which all draw upon Christian and ancient traditions. The exhibition Moments of Eternity considers diverse fascinating aspects that led to a golden age for art medals in the Italian Renaissance.

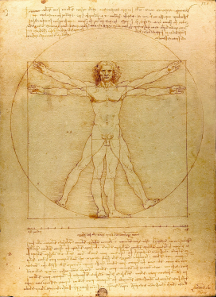

The Vitruvian Man, study of the human proportions following Vitruvius by Leonardo da Vinci (1492). Source: Wikicommons / Photograph: Luc Viatour / www.Lucnix.be.

Our view of the Renaissance is characterized by bold imagery: an epoch when man emerges as an individual in humanistic manner, rediscovering the values, figures and aesthetics of antiquity. This period is also shaped by a ruling class caught in the tension between the struggle for power and artistic sensibilities, military savagery and refined courtly culture. In addition to representing Italy throughout the 15th and 16th centuries as the cradle for medal artwork, the Moments of Eternity exhibition also addresses the ceaseless turmoil within a convoluted political landscape that reflects the socially and culturally active royal courts as well as the wealthy cities of the day.

Pisanello (1395-1455), medal of 1447 on behalf of Cecilia Gonzaga (1424-1451). Reverse: A half-dressed maid taming a unicorn by imposing her hands in a moon scenery. Copyright: Münzkabinett der Stadt Winterthur, Photograph: Lübke & Wiedemann, Stuttgart.

It is no coincidence that at this time of transition, the medal emerged as a new art form – a portable miniature artwork commemorating key intellectual and social trends, which being cast in metal was durable. Produced in limited quantities, and nestling in the palm of the viewer’s hand, a medal fulfilled the need to eternally capture fleeting moments in best manner. In their illustrations, passing events met the immortal. The medal affirmed fama (fame) and memoria (memory). Since they weren’t used for commerce, art medals made ideal presents, being distributed amongst friends and family, dedicated to guests, and assembled by collectors. Others were deposited within the cornerstones of buildings as gifts for ‘eternity’.

The intellectual environment: emergence of Renaissance Humanism

In addition to the medieval conception of mankind characterised by the individual turning towards God to cope with the often traumatic circumstances of daily life and with the hope of redemption in an afterlife, a movement arose returning to the ancient notion of Humanitas.

Sperandio di Mantua (1425/27-after 1504), medal of 1462 on behalf of Giovanni II Bentivoglio, Master of Bologna (1463-1506). Obverse: bust portrait to the left with cap and necklace. Copyright: Münzkabinett der Stadt Winterthur, Photograph: Lübke & Wiedemann, Stuttgart.

Through a combination of knowledge and virtue, individuals should assert their newfound self-belief, whereby each develops the ability to determine their own destiny. This novel conception of the individual is captured in portraits that are no longer the preserve of the ruling elite. Anticipating subsequent developments in painting, medals depicted portraits of merchants, scholars, and other members of society.

Competition with the established arts: the formative role of the medal artists

The Renaissance art medal by virtue of its size allowed sophisticated imagery to be crafted.

Niccolò Fiorentino (1430-1514), medal of 1498 on behalf of Alessandro di Gino Vecchietti (1472-1532), c.1498. Obverse: bust portrait to the right. Copyright: Münzkabinett der Stadt Winterthur, Photograph: Lübke & Wiedemann, Stuttgart.

Assertive and informed artists such as Pisanello and Fiorentino realised the potential, and championed the medal along with other arts such as painting and poetry. The medal should be seen as an artistic and emblematically superior art form.

With regard to the comparison of art forms, a lively debate concerning their relative merits was conducted in the form of paragons. The medal artists, representing their novel artistic craft, participated with pride.

Pisanello (1395-1455), medal of c.1441 on behalf of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan (1450-1466). Reverse: Horse head, besides three books, below sword. Copyright: Münzkabinett der Stadt Winterthur, Photograph: Lübke & Wiedemann, Stuttgart.

Pisanello produced thematically complex medals for the Este court in Ferrara and the Aragonese royal family in Naples – by 1444 linked through marriage – and these may be seen as a reference to the rivalry between the arts. In straightforward symbolism, but with complex allusions to ancient traditions, these medals remain subject to debate. They are not easy to decipher and enigmatic aspects persist.

Unique artefacts

The exhibition Italian Medals from the Renaissance displays unparalleled items from an important Swiss private collection and for the first time makes them accessible to a wider audience. The book for the exhibition by Peter Volz, a renowned expert on Renaissance medals and plaques, is available via the museum shop.

For more information on the opening hours and the exhibition please go to the website of the Winterthur Coin Cabinet.