He was one of the most interesting persons of early modern times: John Frederick of Brunswick-Calenberg (*1625, +1679). To the annoyance of his Lutheran relatives, he converted to the Catholic faith and, by means of a coup d’état, forced his brother George William to cede a major part of the territory to him.

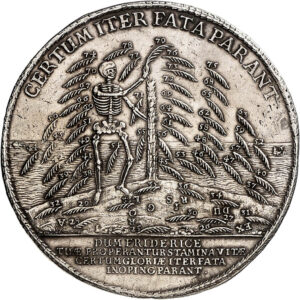

The death of John Frederick is commemorated by an impressive löser, which will be auctioned off as part of the Friedrich Popken Collection on 28th January 2021 by the Osnabrück auction house Künker with an estimate of 75,000 EUR. The löser depicts a skeleton tearing off the leaves from a palm tree. The image had been designed with great care. As the heir of John Frederick of Brunswick-Calenberg gave a detailed account of his funeral in a comprehensive publication, we can understand the role these coins played in the death ritual. And this gives us a clear indication of why Brunswick dukes had lösers minted in the first place.

John Frederick of Brunswick-Calenberg

John Frederick was born on 25 April 1625. He was the third-eldest son of George of Brunswick-Calenberg. Therefore, his chances of becoming the ruler of the duchy were quite poor. Nevertheless, it was a scandal when 27-year-old John Frederick converted to the Catholic faith. After all, the House of Welf, which he was part of, was strictly Lutheran. But a near-death experience may have driven him to change his religion: the Venetian state barge, the Bucintoro, came close to sink the small boat in which John Frederick was watching the spectacle of the Venetian marriage of the doge with the sea.

Was a Catholic entitled to inherit Welf estates in the first place? After the death of his eldest brother, John Frederick avoided any questions that might come up by means of a coup d’état. In this way, he forced his second-eldest brother to negotiate with him and to cede him the principality of Calenberg-Hannover, which had been enlarged by Grubenhagen.

John Frederick proved to be a hardworking and efficient ruler who, in the spirit of absolutism, strengthened the internal structure of his state and pursued a clever foreign policy. As prince in the High Baroque era, he turned his life into a work of art. He founded the Herrenhausen Palace and Gardens, and promoted famous musicians and scholars such as the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. His deeds were noticed beyond the borders of his rule, and thus John Frederick paved the way for his younger brother Ernest Augustus, who was to take over the rule after him, to demand and to be granted the right for the House of Welf to establish a ninth electorate.

It is in this context that we have to understand the magnificent funeral ceremony that Ernest Augustus organised for his brother. John Frederick had already died on 28 December 1679, but his bones were not buried in the princely crypt of Hannover until 21 April 1680. Part of this ceremony was a highly interesting Brunswick löser.

Playing With Images

What do we see on this remarkable löser? First of all, the crowned initials of the deceased in a laurel wreath on the obverse. That is no surprise. Initials were among the most frequently used elements in the Baroque era, and laurel was often used to symbolise the glory of a prince.

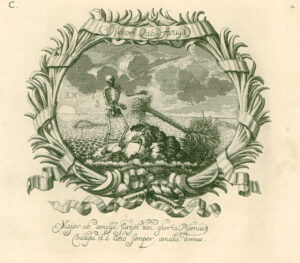

However, the reverse is unusual. It depicts Death as a skeleton tearing off the leaves of a palm tree growing on an island. In the background, we can see the wrecks of sunken ships.

Every single branch that was torn off the palm tree has a number. David Samuel von Madai explained in his taler catalogue of 1766 (Vollständiges Thaler-Cabinet) that the numbers refer to the years of the ruler’s life. At the very bottom we can see a branch marked with the number [16]25, i.e. the year in which John Frederick was born. The branch that Death tears off last bears the number [16]79, i.e. the year of the prince’s death.

On the ground there are letters upside down, which can easily be put together to the ruler’s motto: EX DVRIS GLORIA.

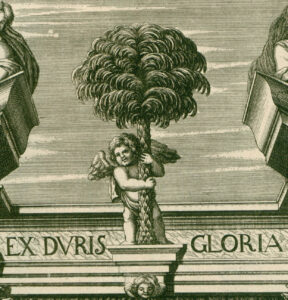

This motto can be found on numerous coins of John Frederick. In a very free translation, it simply means “No pain, no gain”. The palm tree was chosen as a motif because it was considered very difficult to climb it due to the hard, rough bark but its crown was filled with sweet dates.

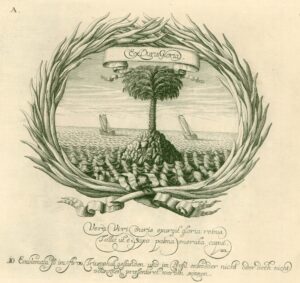

This löser of two reichstalers issued by John Frederick’s successor on the occasion of his accession to power struck at the same time as the funeral löser we are presenting here plays with the images of his predecessor, too, and thus tied in with John Frederick’s successful reign. Ernest Augustus “quotes” the palm tree, the island and the ship. The motto, which could be loosely translated as “The same under different circumstances” probably refers to his elevation in status. The image uses the palm tree as a symbol for the hard work it takes to navigate the ship – of the state? of life? – across the storm-tossed and sunlit sea, past the steep cliffs of the island into the harbour. The wheel – the coat of arms of Osnabrück, where Ernest Augustus served as bishop, and at the same time an allusion to fate – is in God’s hands. Ambiguous emblems that posed a riddle for the educated class were very popular at the time.

Our löser issued on the occasion of John Frederick’s death is variegating these elements, too. The palm tree is turned into a tree of life, which Death tears apart piece by piece. The translation of the inscription reads as follows: A safe path is provided by the divine will. And in the exergue: While your thread of life is hastily unwound, Frederick, fate unexpectedly paves a safe path to glory.

But what role did this magnificent coin of 10 reichstalers play in the death ritual? There is a book that can help us understand it. Ernest Augustus commissioned Johann Wilhelm Lange, a well-known engraver at that time, to create a chronicle of the funeral illustrated with 86 copper engravings.

Baroque Death Rituals

We have to keep in mind that occasions such as baptisms, weddings or funerals were used for self-representation in baroque culture and therefore grand ceremonies were organised to celebrate such events. Every celebration reflected the rank of the organiser and his claims. That’s why architects and carpenters, heralds and poets, cooks and tailors worked overtime to impress the envoys who attended the event. Ernest Augustus invested a fortune in order to make the potential of Brunswick-Calenberg known throughout Europe.

The mastermind behind the funeral ceremony was the advisory council and librarian Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz who is rather known as a philosopher today. He designed the complex iconographic programme and the ceremony for the funeral procession. To make sure the effect wasn’t limited to the envoys present at the funeral, Ernest Augustus had an illustrated book published five years after the funeral, which chronicled every little detail of the ceremony. The illustrated book – which also contained all funeral orations and the biography of the deceased written by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz – could be sent as a gift to important princely courts.

The work provides us with the rare opportunity to understand the role of a coin in the ritual and the extent to which coins were part of the iconographic programme. The title page picks up a motif that was often featured on the prince’s coins during his lifetime: the palm tree and the motto EX DVRIS GLORIA. We will encounter this palm tree again and again.

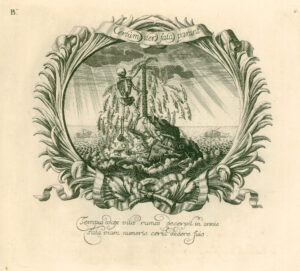

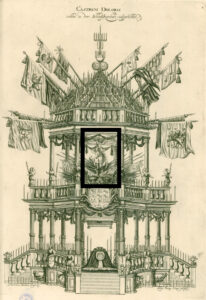

When we stand in front of baroque churches and castles, we only see a fraction of what the architects of this era created. Again and again, elaborate but transient decorations were made for various occasions. One of them can be seen on this plate. It depicts the wooden gate that covered the stone portal of the Hannover castle church during the funeral. For numismatists, the painting at the top of the gate is particularly noteworthy: We see Death as a skeleton felling the palm tree of John Frederick’s emblem. The ships in the background with broken rigging are interesting, too.

Although figure 8 might suggest otherwise, we shouldn’t think of this gate as a one-dimensional piece. There were elaborately decorated side panels depicting other emblems. The book shows all ten emblems. We already know some of them: for example the prince’s emblem used on coins that consists of an island with a palm tree, sailing ships and the motto EX DVRIS GLORIA.

Among these depictions is the image featured on our löser. The translation of the motto shown at the top reads as follows: Voracious time picks the branches of life.

Another emblem depicted on the gate shows a slightly different image: With pick and spade, Death digs out the palm tree together with the roots. The ships capsized. The motto EX DVRIS GLORIA ascends up to heaven.

Once the funeral procession made its way through the gate at the entrance, they entered the church where the castrum doloris was erected at the centre. This term was used to describe a wooden construction in the form of a chapel built for the funeral. The coffin was in the middle of it. Under this construction, ecclesiastical funeral rites took place.

The castrum doloris also served the purpose of reminding those present of the deceased once more. Therefore, above the catafalque we can see the leaping horse of the House of Welf, a genius sitting on it, carrying the dug out palm tree with roots in his hands.

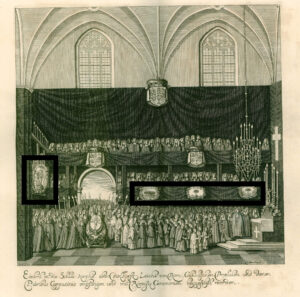

This image shows how Catholic priests and Capuchin monks accompany the coffin into the church together with courtiers. The architectural elements of the church were altered to suit the occasion: the walls were covered with black fabric on which colourful signs with variations of the palm tree emblem can be seen clearly.

The paramount role of the image that we know from our löser is illustrated by the fact that this emblem is much larger and shows in a more prominent position than other symbols.

But Why Were These Lösers Minted in the First Place?

It becomes apparent that the image on our löser is closely connected to the iconographic programme designed by Leipzig for the funeral of John Frederick of Brunswick-Calenberg. But for what purpose were the coins minted? And why are there coins of so many different, finely graded weights? To understand this, we have to study the customs of the time a little.

There were gifts for every ritual event. We can still see traces of early modern gift culture when employers transfer a 13th month pay in December and business partners send Christmas gifts to each other. However, in early modern times people did not exchange gifts on Christmas but for the New Year. The amount of presents and their value were precisely defined according to the status of the giver and the recipient.

In rare cases, sources tell us about such grading of gifts. The Vienna City Council, for example, decided in 1575 that: “on the occasion of the New Year, every municipal prosecutor, mayor and judge must be honoured by the City Council with a golden Salvator pfennig worth eight Hungarian gold guldens featuring the common municipal coat of arms and every member of the Interior Council also must be presented with such a pfennig worth six ducats.”

Gifts were not only exchanged for the New Year but also on the occasion of baptisms, weddings and funerals. Whoever could afford it had objects created for such occasions that had monetary value and commemorated the event. That’s why there are so many baptism, wedding and death talers as well as New Year’s guldens in the numismatic field of the German States.

For the funeral of John Frederick, which had been organised with much effort, an entire series of coins was minted, which were distributed according to the rank of the attendees. After all, representatives of various ranks participated in the funeral procession: noblemen, citizens and, not to forget, the simple folk waiting along the streets. The coins of the smallest denomination were reserved for them.

It is crucial that the value of these commemorative coins, which were often called pfennigs back then, was connected to that of a taler. Therefore they had a double function. As commemorative coins, they recalled the funeral, and at the same time they were of financial importance for the envoys of a town or a prince, who paid a lot of money to be able to attend the funeral.

The servants and officials of the palace, who did an extraordinary work during the event, may have also been given / paid by means of such commemorative coins. Of course, they did not get splendid lösers of 10 talers like the one offered at Künker. Those were definitely given to the participants of the highest rank. For the servants, coins of lower value were minted – all the way down to 1/24 taler pieces, which were probably thrown among the people.

All these coins are depicted in the work on the funeral of John Frederick of Brunswick-Calenberg.

Therefore we find ourselves in the fortunate position of having an illustrated book that provides us with the exact iconographic background for the design of a coin image. This example illustrates that we have to think of all coin images as being part of a much larger Gesamtkunstwerk. Baptismal, wedding and death talers were part of a ritual, but, of course, they had a secondary function as a means of payment.

It would be commendable to compare more images on coins with contemporary illustration that is still available today. We would certainly learn a lot about the fact that coins were much more than simple means of payment.

This extremely rare löser will be offered at Künker in Osnabrück on 28th January 2021 with an estimate of 75,000 EUR. You can find all coins of this auction on the website of Künker.

Here you can read a comprehensive auction preview.