by Franky Leeuwerck

August 17, 2017 – We are in the year 2889. By then, all objects in museums are virtualized. People can download a perfect but scaled copy of any thinkable museum object and have it rendered in their living room as a tangible three-dimensional image. The objects that are speaking volumes are the ones the general public like the most. And you? Well, you are an archaeologist specialized in 20th century financial artefacts.

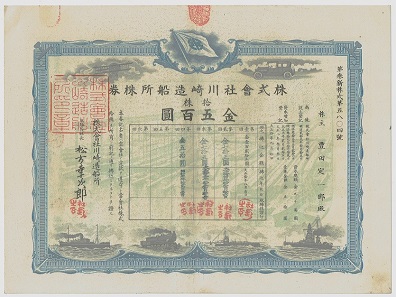

That day you are excavating a chamber at an ancient site which seems to be an office building from the 1960s. Yes, that is funny, back then people used to assemble all day long in a dedicated building to do office work. Anyway, the chamber you are working on, contains a safe weighing about 100 pounds. Your hand-scanner tells you there are documents inside the safe. With your tools, you manage to open it in no time. Wow, the parcel inside contains a set of old stock certificates. In the 20th century, people printed shares on paper for representing ownership in companies. Most of these certificates perished. One of the shares stands out from the others. It is speaking volumes.

A Japanese 20th century share certificate.

With a PhD in Ancient Oriental Languages and Cultures, you translate the long line of characters on top. It is ancient Japanese, and you need to read it in the old way: from right to left.

A detail of the Japanese inscription.

“Kabushiki Kaisya”, are the first words and mean stock/limited company. A common term on Japanese certificates. You mouth the following word much slower: “Kawa” and “saki”, together “Kawasaki”. Aha, that’s interesting, halfway now.

Already from the start you identified the last two symbols, “Kabuken” (“share certificate”). Then you speak loudly, “Zosen” (shipbuilding) … “Tokoro” (place). Wait a minute, together they form “Zosensho” (shipyard)! You have figured it out: “Kabushiki Kaisya Kawasaki Zosensho Kabuken”! I found a share in the Kawasaki Shipyard Co. Ltd. With your hand-scanner you look up the flag printed on the share. Yep, that is the one.

Six months later, a new exhibition of the objects unearthed by you is launched at the Central Museum. The Kawasaki share is one of the highlights. As one of the museum’s educators, you are leading a school group around the show. Of course, you spend time on the Kawasaki and explain all about the way business initiatives and innovations were financed 900 years ago. Some of the kids are babbling on anything but the tour, others look a bit bored. One of the kids raises its arm. “Yes?” The group now turns quiet and looks at you first, then at the kid who says, “If this piece of paper was meant to finance a business, what type of business would that have been?” The other kids are speechless and are now all staring at you.

The flag on the Kawasaki share.

Happy with the question and all the attention you have, you clarify “Well, that could be anything you can think of, but in this case, you can see from the vignettes, the little pictures on the certificate, what this company was all about.”

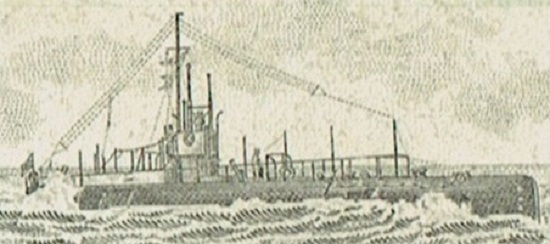

The ship on the share shows what kind of business the Kawasaki company made.

Now, for the first time, all the kids turn to the display case and inspect the Kawasaki share. “They made ships!”, shouts one of them and they all look at you again. “That is correct! The Kawasaki Shipyard Company was founded in 1896 and already one year later the company completed the Ivomaru, its first ship. If you look carefully, you can see a drawing of the shipyard behind the lettering. At Kawasaki they were very inventive. In 1906 they completed their first submarine. They even made battlecruisers like the Haruna, which was a warship of the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War I and II!”

After reducing contrast, the underprint of the Kawasaki share reveals an image of a dockyard with ships under construction.

“And they also made cars … and airplanes … and locomotives!”, they tell each other and leave their finger prints all over the display case. The kid that posed the first question, raises its arm again. “Yes?”, you wonder amused, “What’s your name?” The whole group answers instead, “Sidney!” “Yes, Sidney, what is it?”

This cartouche-alike signature represents the name of a high official or a very important person, in this case Matsukata Kojiro.

Again, the group turns quiet and Sidney continues, “These large vertical signs, they look like a cartouche. Is this from a Pharaoh?” To everyone’s reassurance you can not suppress a smile. “Sidney, that’s is actually a good question. A cartouche, an oval with a horizontal line at one end, encloses a royal name and was used in Ancient Egypt.” The boys and girls look disappointed but turn their heads to the share certificate again when you proceed, “But, as is the case with this Kawasaki share, a signature of a high official or very important person was often printed in such a vertical way.”

“Do you see these five large vertically written characters over here?”, and with your light pen you point out the position on the share. “The first two stand for Matsukata.” Some children try to mumble the word. “The last three are Kojiro.” “So from top to bottom you read Matsukata Kojiro.” “Now repeat all together!” They all chant Matsukato Kojiro in unison.

“Matsukata Kojiro was born in 1865, that’s more than a 1,000 years ago, and he was the son of the Prime Minister of Japan. Kojiro became president of the Kawasaki Shipyard Company in 1896.”

“Was he rich?”, someone asks. “Oh yes, his business was very successful for some time. Kojiro also wanted to give something in return to the people in his country. With the fortune he accumulated, he bought lots of Western European and Japanese art and wanted to build an art museum. Unfortunately he died in 1950 before he could realize his dream. But soon large parts of his collection found a home in Japan’s National Museum of Western Art in Ueno and the Tokyo National Museum.”

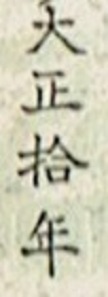

The date “1921” in Japanese.

“I have another question”, adds Sidney, “My dad rides a Kawasaki motorbike, why don’t we see a motorbike on the share?” Some kids nod, they obviously know Sidney’s father. “Great question Sidney.” The group is proud to have Sidney on board. “You see, this share was issued in 1921”, and you point out the date on the Kawasaki share. “In Japan, years were then expressed as the number of years in the reign of the emperor starting with 1. One Japanese symbol represents Emperor Taisho, another one stands for 10 and the third is the word for year. Taisho’s first year of reign is 1912. So the date we see here is 1912 + 10-1 which results in 1921. Now, that was easy, isn’t it?”. Everyone in the group tries to convince one another that it was easy. So you continue, “Kawasaki started producing motorcycles more than 30 years later; therefore we see no motorbike on the share. The first motorbikes were produced by Kawasaki’s Aircraft Division. That’s why the emblem’s on their fuel tanks looked like the Kawasaki flag within a wing.”

Reading from right to left the watermark of the Kawasaki share says: “1×10 share certificates; Kabushiki Kaisya = Co., Ltd.; Kawasaki Shipyard.” In 1969 the Kawasaki Shipyard company merges with its earlier spin-offs, Kawasaki Rolling Stock Manufacturing and Kawasaki Aircraft, into Kawasaki Heavy Industries.

Later at home, Sidney tells mom and dad about the museum visit. The child activates the home visualizer and downloads a virtual replica of the Kawasaki share. It rotates slowly in the air when Sidney walks around it. “Omigosh!” The floor lamp shines through the image and a large watermark becomes visible.

You can learn more on the company at Wikipedia’s Kawasaki Shipbuilding Corporation article.

In another article Franky has explained how to read Japanese dates on stocks and bonds.

This article appeared on Franky’s Scripophily BlogSpot. We republish it courtesy of the author. If you are interested in scripophily, that is in historical shares and bonds, don’t miss his blog!