October 18, 2012 – On October 12, 2012 a conference was held at Hasegg Castle. Six researchers form five different countries were invited to investigate the history of innovation at the Hall Mint. One question united all these works: for what reason it was Hall that became a mint which spread new ideas through whole Europe?

Andreas Ablinger of Hall AG and Werner Nuding, vice-mayor and creator of the roller coining machine replica. Photo: Münze Hall.

The Hall Mint hosted the event. Here, you will not only find a museum of minting technique. Hall is also the home of the Tyrolean Numismatic Society. It is thanks to this organization and its indefatigable efforts that numismatics has become an essential topic in local politics at Hall. How many towns do you know whose mayor is member of a coin club at the same time?

Ursula Kampmann and Kurt Wyprächtiger present the first paper, in the background Björn Schöpe who moderated the discussion. Photo: Münze Hall.

The morning was dedicated to the roller coining machine. At least, it was from Hall that this innovation found its way into the world. However, Ursula Kampmann and Kurt Wyprächtiger emphasized in their paper that the roller coining machine was not invented in this place.

Henry II (1547-1559). Teston du moulin 1554, Paris. From Künker Auction 217 (2012), 2193.

In fact, according to our sources Augsburg was probably the town that had the first operating roller coining machines. And, indeed, a craftsman from Augsburg sold one to an ambassador of the French King for 3,000 écu. This machine was placed on the end of Ile de la Cité producing more beautiful coins than ever seen by any of the mint’s craftsmen. In the ‘mill’ as the roller coining machine was called, less men were needed, though. And moreover they had to know completely different things than a traditional mint fellow. Thus, when due to the wars of religion the royal court was too distracted from paying much attention to the coining, the persons responsible simply shut down the roller coining machine.

Zurich. Thaler 1559 of Jakob Stampfer. From Leu Numismatik AG Auction 85 (2002), 555.

In Zurich, Jakob Stampfer constructed a roller coining machine for his extensive mass production of coins. Though, this reached an impasse too. Stampfer was indeed a proud craftsman who would never undersell his knowledge. Hence, when his former collaborators sold cheap his roller coining machine to other minting authorities, he lost interest and passed into administration. And that was a pity since Stampfer was probably the most capable coin engraver of the sixteenth century.

Dr Romedio Schmitz-Esser has a lot of fans in Hall since he was their city historian for a couple of years. Photo: Münze Hall.

Dr Romedio Schmitz-Esser’s paper started from the moment when the roller coining machine was installed in Tyrol. He reconstructed with exemplary archive research how thin the staffing level actually was. Cutting the rollers for this new kind of machine and controlling the technical work flow required specific training and much experience. There were only a few, though, who had this knowledge. On the contrary the rest of the work could be accomplished by assistant workers with little training. Indeed, this definitely did not contribute to leading other mints to jump at this avant-garde technique.

Ferdinand II (Count of Tyrol 1564-1595). Reichsthaler, no year (1577/1599), Hall. From Peus Auction 407 (2012), 2789.)

It were indeed the royal courts that encouraged the roller coining machine rather than the mints. Ferdinand II, Count of Tyrol, was very proud of this invention. All the diplomats and rulers who visited him were brought to Hall where they were expected to admire the powerful machines in the working process. Like the Chamber of Art and Curiosities in Ambras Castle the Hall Mint aimed at impressing and celebrating the greatness of the Count of Tyrol.

Replica of a roller coining machine in the Hall Mint. Photo: KW.

The roller coining machine enabled Ferdinand to negotiate on an equal footing with his more powerful Habsburg relatives in Vienna and Madrid. And therefore he was certainly glad when Philipp II coaxed him to send technicians who would install roller coining machines in other Habsburg mints too. Thus Ensisheim and Segovia were modernized with technique from Hall.

Dr Glenn Murray / Segovia – a constant fighter for a coin museum in Segovia. Photo: Münze Hall.

Segovia has its own expert: Glenn Murray, an authentic coin enthusiast. The numismatic world has to thank Glenn Murray that today the historical mint in Segovia is no longer a ruin on the edge of collapsing instantly.

Felipe II (1556-1598). 8 Reales 1589, Segovia. From Künker Auction 188 (2011), 342.

He spoke about the fundamental influence the technique from Hall had not only on Spain but the New World as well. Did you know, for example that the coins produced with the roller coining machine were the very first Spanish coins that featured the year of striking regularly?

By archaeological findings and thanks to his zealous research Glenn Murray reconstructed what was technically possible at this epoch. Only the roller coining permitted to realize more fractions one beside the other on one single fillet, or those splendid silver issues on high denomination.

DDr Helmut Rizzolli is not only THE expert on Tyrolean Middle Ages but at the same time a particularly humorous and charming lecturer. Photo: Münze Hall.

The afternoon was no longer dedicated to technical questions but to the most famous innovation from Hall. After all it was here were the world’s first high nomination silver coin was minted. DDr Helmut Rizzolli led us through the prehistory of this issue. He called attention to the fact that for decades coins from Tyrol had borne a mark of guarantee, of their value so to speak.

Sigismund the Wealthy (1446-1496). Guldiner 1486, Hall. From Künker Auction 201 (2012), 379.

However, on the half guldiner and the guldiner this mark is missing. Instead we are confronted with a portrait of the count and, on the reverse, a knight being expressions of representation. Why not suppose, as Mr Rizzolli proposed rather heretically, that this money was not designed for the market but rather for reverence and diplomatic gifts, just for test purpose as we may say. It would be thus halfway between a coin and a medal.

Economic historian Prof. Dr Markus Denzel gave an understanding of all the facts and dates with his vivid presentation. Photo: Münze Hall.

Anyway, a high denomination silver coin was a solution to the European problem. Because an increasing mass of coins was required, while gold – as utilized in the traditional coinage applied to the long distance trade – was available only in limited quantity. Silver, on the other hand, was abundant. And thus the guldiner spread from Tyrol all over the world.

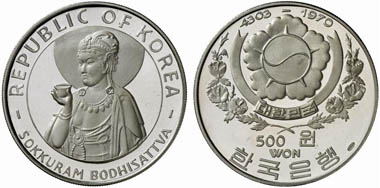

South Korea. 500 Won 1970. From Künker Auction 217 (2012), 3363.

German Marks, Swiss Francs, Spanish Pesetas, Bulgarian Lews – they all share the origin from the first high denomination silver coin. And, as economic historian Prof. Dr Markus Denzel explained, this goes as well for many coins overseas. We all know that the dollar takes his name from the thaler. But maybe we would not have linked the Chinese Yuan, the Korean Won or the Vietnamese Dong to this European innovation.

The speakers at the conference in Hall. Photo: Münze Hall.

It has been an extremely rewarding conference leading in the synopsis of previous research results to completely new ideas. Those who were not able to assist can console themselves: the conference papers are going to be published in the middle of the next year. And there will be a printed version in German and English as well since the relevance of the Hall Mint is definitely not limited to the German speaking world.

If you want to learn more about the Hall Mint, please click here.