The first sovereigns were minted in England in 1489. However, over time other coin types replaced sovereigns in circulation money. It was not until 1817 that sovereigns were minted again; and they have been produced ever since (with an interruption between 1917 and 1957).

A standard was set stipulating that the coins be made of .916 gold and that the gross weight be 7.98 grams. Sovereigns consist of 7.32 grams of gold. The diameter is 22.05 mm. Sovereigns are made from a gold/copper or a gold/copper-silver alloy. The dual composition of the material is the reason why the coins display different shades.

Newly minted coins almost always have a uniform graphic depiction. The obverse features the portrait of the (then) ruling English Queen/King and a respective legend; the reverse depicts Saint George sitting on a horse with his sword killing a dragon. The indication of the mint can be found at the centre of the rock on which the dragon lies. The year is engraved directly below. The reverse of the rim is surrounded by small squares.

Alterations of this design (a coat of arms instead of Saint George; mint and denomination indicated at another place) can be found on coins of the time of Queen Victoria. Coins were minted in 6 cities, which can be identified thanks to the mint marks:

- No mint mark – London,

- M – Melbourne,

- S – Sydney,

- C – Ottawa,

- P – Perth,

- SA – Pretoria (South Africa),

- I – Bombay only 1918; 2013-2016 Delhi.

The Sovereign: One of the Most Popular Coins – Also Among Counterfeiters

Just like any circulation coin, sovereigns have been forged. It is very difficult to estimate how many counterfeits are in circulation – and there are two main reasons for it. On the one hand, the coins circulated in a very vast territory (which, for historical reasons, was not limited to Europe), on the other hand, sovereigns were often traded at their material value and considered material coins. That means that large quantities of coins were simply melted down. We do not know how many forgeries were hidden among the real coins.

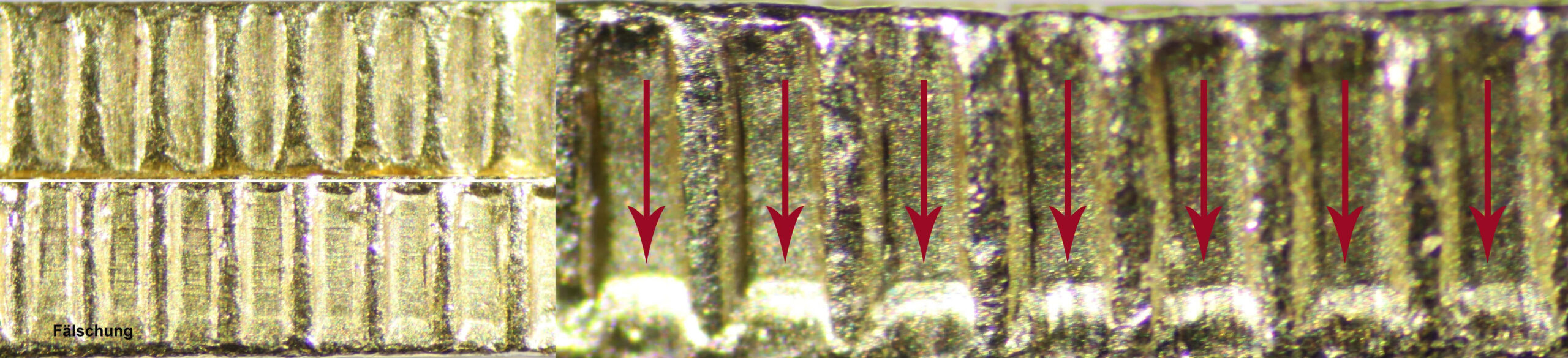

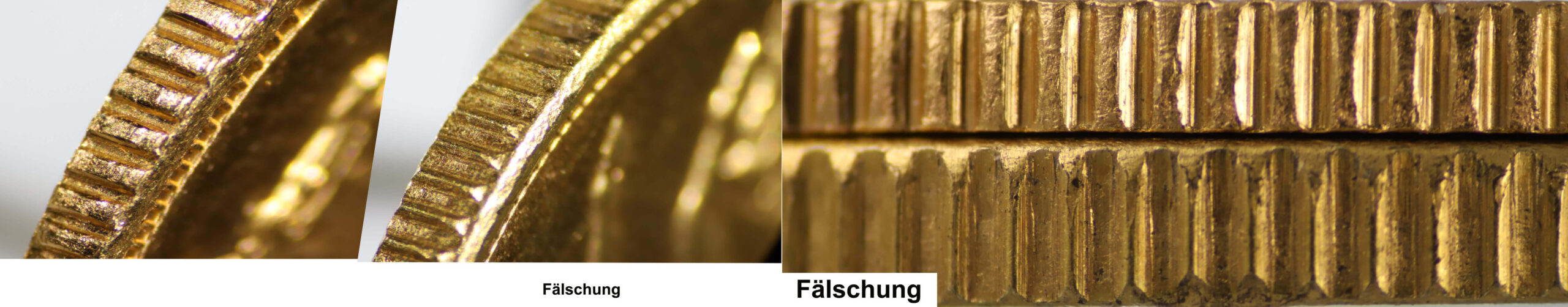

Unlike the forgeries of other coins, which are produced by using both minting and casting methods, counterfeit sovereigns were mostly cast. This does not only apply to older specimens, such as those of Victoria or George V, but to all forgeries including the coins produced in the 60s of the last century. What’s interesting is the fact that almost all cast coins have a mechanically reworked rim. The nicks were added after casting the coin. This gives the counterfeiter some advantages. It means that reworking the rim in order to adjust the diameter and the weight to the original parameters is easier and leaves no traces. Moreover, the places where casting channels were attached are no longer visible. However, there is also a disadvantage to this method: The nicks in the rim differ – sometimes very clearly – from the original piece because they were not made precisely. This is not only true regarding the depth but also the overall shape of the nick.

From all the coins I have identified as forgeries so far, a system emerged. The sovereigns that are forged most frequently are those of George V. Second are coins featuring Victoria with the small crown, followed by Edward VII. I have often found several forgeries of Victoria with the veil and Elizabeth II. There are many varieties of each of these groups. They differ regarding the features that can indicate that the piece was forged: year, mint and, of course, quality.

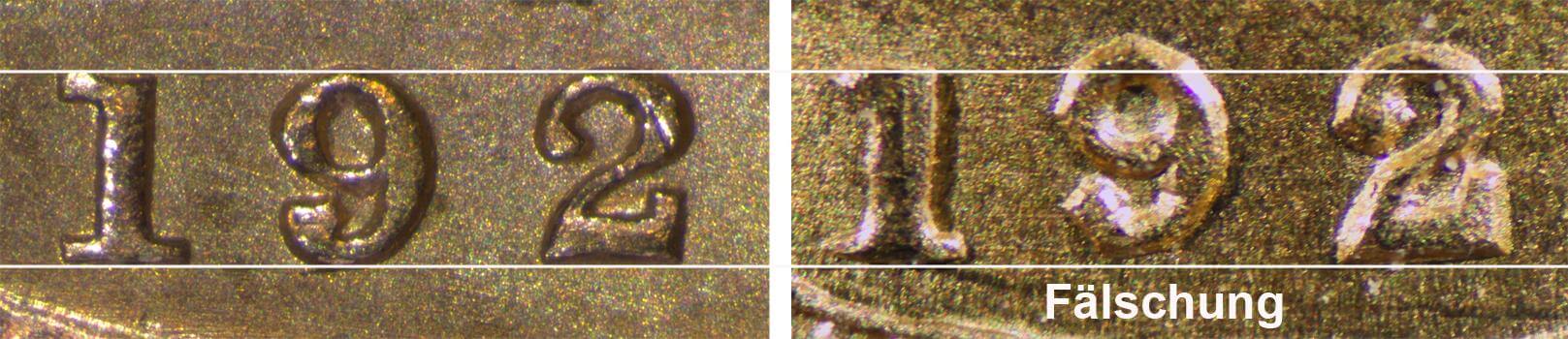

Specific Counterfeits: Sovereign 1922 London

As an example I chose an interesting counterfeit that is technically well-made. It is a coin with a mechanically cut rim. The forgery does not have many features that give it away, nevertheless, it can be easily identified as a counterfeit.

At first sight, the coin does not really differ from the original piece. The surface feels a bit too smooth and the border is quite sharp, which can be unusual for circulation coins of 1922. The diameter is 22.25 mm, the weight 7.95 g.

The composition of the coin’s alloy is as follows (measured at the surface, in %):

| Au | Ag | Pt | Pd | Cu | Fe | W |

| 93.6 | 0.097 | 0.02 | 0.005 | 6.32 | 0.019 | 0.064 |

The electrical conductivity is 9.6 Ms/m – at 120 KHz.

There are also two features that deviate from the original piece on the reverse.

All these features are clear and well visible, but only with a magnification of about 2 to 4 times.

However, to determine that a coin is a forgery, you only need to look in a catalogue. The 1922 sovereigns of George V weren’t minted in London. Therefore, the coin should feature a mint mark indicating the mint; but it doesn’t.

Specific Counterfeits: Sovereign 1964

The second example is the least common counterfeit. It is a forged sovereign of Elizabeth II. I only know of three years that were forged, namely 1958, 1964 and 1966. The counterfeit of the 1958 coin type was created through a minting process and is of high quality, which makes it hard to identify. The forgeries of 1966 sovereigns are a different matter. The specimens – 1966 – are certainly not among the greatest works of counterfeiters. It must also be said that this version can only be found on the market on rare occasions. Forgery of the year 1964 are the ones that occur most frequently.

It cannot be determined when this counterfeit was made. Due to the fine casting quality, one can assume that the piece was produced by means of a vacuum casting machine.

It is a cast coin with a mechanically cut rim.

The composition of the coin’s alloy is as follows (measured at the surface, in %):

| Au | Ag | Cu | Zn |

| 4.49 | 0.14 | 67.1 | 28.3 |

The density is 8.74 g/cm³ and the electrical conductivity 16.7 MS/m at 120 KHz.

It has the same diameter as the original piece. Deviations from the original become apparent regarding the thickness. The authentic coin is 1.36 mm thick, the counterfeit 1.56 mm.

Regardless of their year of minting, all sovereigns are still legal tender today. One more reason to examine the coins with great care. When measuring these parameters, there may be certain deviations depending on the type of counterfeit you are dealing with and the testing equipment used. It is possible that counterfeits made in the same way show small differences. The reason for this can be the non-homogeneous alloy in the case of cast coins, and the additional treatment of the surface regarding minted coins.

If the above-mentioned information has motivated you to check your own pieces, please take into account that there may be slight deviations when comparing your results to my figures regarding the physical parameters. This can be due to, among other things, the use of other testing equipment. Especially regarding electrical conductivity, the composition of the alloy and density there may be minor deviations. To compare the results, please keep in mind that I used the following devices:

- Density: Sartorius analytical balance

- Electrical conductivity: Sigmascope Gold C

- Composition of the alloy: XRAY XAN 220

If you want to know more about the author’s expertise, read our Who’s Who about Peter Zgorzynski.

In other parts of this series, the author examined counterfeits of Swiss vreneli coins and Austrian ducats.

He also dedicated an article to the subject of tungsten counterfeits – for all those who want to know all the details.

You can find out more about identifying counterfeits in our four-part series “How to detect forgeries”: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4.

NGC is also committed to providing customers with a tool to detect counterfeits.