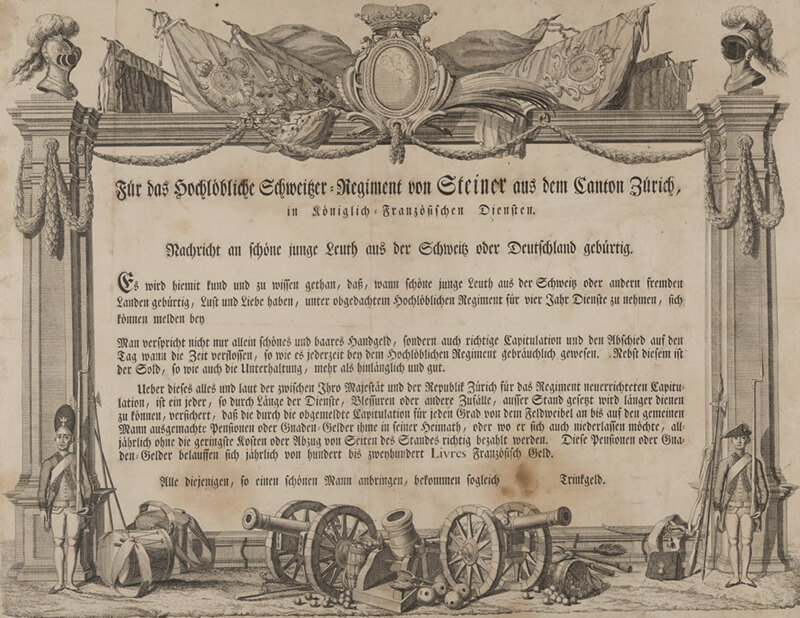

They had to be ‘handsome’, the men for Maria Jakobea Zurlauben (1658-1716). Tall guys of robust build. ‘Des beaux hommes’, as her brother Beat Heinrich Josef (1663-1706) used to say. They came from everywhere: Central Switzerland, the area now called the Aargau, March, Zürcher Landschaft and Eastern Switzerland, southern Germany and even Bohemia. They didn’t stay long. Their board and lodging at the ‘Löwen’ inn in Zug was too expensive. As soon as ‘Frau Hauptmannin’ Zurlauben had gathered together a dozen men who had committed to mercenary service by accepting prest money, she immediately dispatched the recruits on the march westwards to France, with an escort of armed soldiers.

At the French royal court, the Zurlaubens owned a half company of guards, which they had managed for generations. It was the centrepiece of the family’s mercenary business, allowing them exclusive access to court society. As part of the Swiss Guards, the company belonged to the monarch’s external bodyguard. The company guarded the royal residences, accompanied the king when he travelled, and fought in campaigns. Anyone who was that close to the king had to make something of it. So Beat Heinrich Josef Zurlauben, owner and captain of the guard company, only took perfectly proportioned recruits – the ‘handsome ones’. The less ‘handsome’ men that his sister sent him from Zug he allocated to the family’s other companies of mercenaries in France.

Women in the mercenary business

In the old Swiss Confederacy, the fact that a woman like Maria Jakobea Zurlauben, a member of a wealthy Zug family involved in the mercenary business and magistrate activities, organised the recruitment of mercenaries was actually the rule rather than the exception. But in the historiography, women like her were and still are invisible. They are little more than supernumeraries. Historians – most of them men – tell the story of the pre-modern mercenary business families just as they were recounted, in their glorious family chronicles, coats of arms and family trees, by the 17th and 18th century protagonists whom those historians research: as a succession of great men. As an account of war heroes who went into battle, earned aristocratic titles and bequeathed their companies to their sons as separate inheritances.

Not infrequently, that was purely wishful thinking, because women were generally entitled to equal shares in an inheritance and were sometimes co-owners or even sole owners of military companies. In many such companies female relatives invested their own money, whether as inheritance or as a loan. And many women worked in the family mercenary business. These services were not given purely out of family devotion. The mercenary business was a family enterprise in which virtually all relatives were required to participate, but they also profited – some more than others – from the resulting benefits: the financial returns, the social prestige, the access to the courtly society and training positions for their boys.

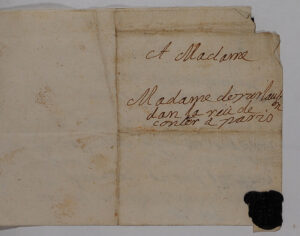

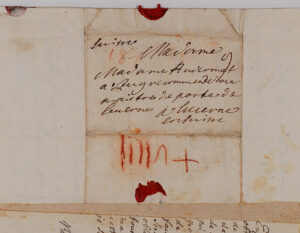

Maria Jakobea Zurlauben, for example, ran the family’s operations in Zug for many years and acted as a link to her brothers outside the country. It was a busy position, especially in times of war which, during the reign of King Louis XIV (1638-1715), were plentiful. Those volunteering for service reported directly to the ‘Frau Hauptmannin’, the lady captain. She also coordinated a network of subscription agents who systematically targeted men for recruitment. The peak activity period was in winter. The company headcounts had to be topped up in good time for medical examinations in the spring. To keep each other informed, the siblings often sent several letters each week: How many recruits did the companies need? How many had deserted en route, or had had to be left behind in infirmaries? How much cash was left to pay the hostelry bills, prest money, wages for the recruitment agents, guides and messengers, and to buy tobacco, clothes and new shoes for the recruits? Incidentally, the soldiers had to pay back most of this money to the company owner after their arrival in France.

Maria Jakobea’s sister, ‘Frau Landammännin’ Maria Barbara Zurlauben (1660-1724), also recruited soldiers in Zug. Surviving documents show that she was also entrusted with the actual management of the company: she took receipt of the monthly accounts and reports sent in by the officers in France, and corresponded with them about current problems. The women were not simply stand-ins for absent men. Maria Jakobea Zurlauben paid for advertising from her own resources. After the death of Beat Heinrich Josef, she travelled to Paris to sift through his estate and claim her money. She also participated in the financial profits of the mercenary business, and her husband was given an officer’s post in his brother-in-law’s company. In return, Maria Jakobea had to take their aged mother into her household and look after her.

The portraits of highly decorated mercenary leaders, their ostentatious stately homes, heroic tales and genealogies extending centuries back into the past provide a glamorous backdrop for the seductively simple story of a dynastically organised mercenary business: within individual dynastic houses, companies of mercenaries were passed on, down the generations, to the eldest son, who as the new head of the family called the shots and demanded obedience from other relatives. However, a glance at the womenfolk shows that the story is more complicated. The mercenary business was in fact a type of collectively owned enterprise, embedded in a convoluted network of multi-faceted relationships and claims of numerous relatives amongst whom a balance had constantly to be struck.

This article was originally published on the blog of the Swiss National Museum.

We thank the Swiss National Museum for having allowed us to republish the article.

If you want to learn more on this topic we recommend the archive collection of the family Zurlauben in the Aargau canton library, Acta Helvetica.

We further recommend the blog of the Swiss National Museum.

And this is the website of the Swiss National Museum.